Topics

on Japanese Law by Yoshihisa NOMI

(Prof.Emeritus Tokyo University)

Jump to TOP Page (more information on Japanese Law)

I A Short History of the Civil Code of Japan

(1) The Meiji Restoration and the Reform of Political and Legal System

The Tokugawa Shogun

returned his political power to the Emperor in 1867 and the new Government has

started. This is the beginning of the Meiji Restoration. The next year 1868 was

named Meiji to commemorate the Restoration. The Restoration was not a simple

shift of power from the Tokugawa Family to the Emperor. It was more of a

revolution by the lower Samurai class (Samurais belong to the

warrior class but they usually worked as bureaucrats in the feudal governments)

who feared that without a strong unified modern state Japan will be occupied by

the mighty western nations. Opium war between China and Great Britain was the

alarm.

The

Japanese Government rapidly introduced western political and legal system to

modernize the country. In 1868 the 1st year of Meiji the capital of the State

was moved from Kyoto to Tokyo. There were many things to do for the new

government. The priority was to establish a new political and administrative

structure of the central government and the local government. The top of the

state was the Emperor. To support the Emperor, the administration system Dajokan

(the Grand Council) was established. The head of the Dajokan was called

the Dajo-Daijin(the Chief of the Council). Under the Dajokan

there were 6 ministries, Minbu-sho (Ministry of Internal Affairs), Okura-sho(Ministry

of Finance), Hyobu-sho(Ministry of Military Affairs), Gyobu-sho(Ministry

of Criminal Affairs), Kunai-sho (Ministry of Imperial Household), Gaimu-sho(Ministry

of Foreign Affairs) and later Shiho-sho(Ministry of Justice ) and Monbu-sho(Ministry

of Education) was added. There was no division of powers. All the power was

concentrated in Dajokan and to the Emperor.

The

reform of the local government system was much more difficult. Under the Tokugawa

feudal regime, the Tokugawa Bakufu (the central government) did not directly

ruled all the territories in Japan, but only the important cities and places.

The rest of the territories were ruled by the local lords and the areas they

ruled were called Han. Under the new Meiji government it was absolutely

necessary to deprive the power of the local lords and abolished the local

political system of Han. It is amazing how this was achieved. Without

great turmoil all the local lords agreed to relinquish their power. In 1871

instead of Han now Ken(prefectures) were established. To make the

transition smooth the former land lords were usually appointed as the governor

of the prefecture, but gradually they were replaced by the bureaucrats

appointed by the central government.

Also

worth mentioning is the abolishment of the social classes. In Tokugawa era

the society was divided in 3 classes.The aristocrats, the samurais, and the

commoners (peasants, artisans, merchants).The aristocrats and samurais were the

ruling class and had privileges. What to do with these classes was a big

problem. The government decided to keep the aristocracy as a shield to protect

the imperial family, though reforming it by adding the former land lords and

those who contributed to new government. They formed the new aristocracy (Kazoku).

But the status of samurai was abolished. They were united with the commoners

[1] . This was especially necessary to create a modern military force which

cannot be supplied only from the samurai class but also from the commoners.

This brought strong discontent among the samurai class. There were many rebels

led by the former samurais against the new policy of the government. But they

were all suppressed by the government, sometimes by the army constructed by the

commoners.

F.N [1] Order of the Dajokan 1876 No.38 prohibited anyone to wear a sword, In

the Tokugawa era sword was the symbol of samurai.

(2) Judicial Reform

Along with the reform

of political and administrative system establishment of a new legal system was

necessary. In 1875 the Supreme Court of Judicature was established following

the French model of Cour de Cassation. Lower courts were also established. But

the new laws to be applied in the court were not ready. As for the civil cases

there was no Civil Code yet. The project to draft a new civil code has just

begun following model of the French Civil Code . Without enough laws and statutes

how did the judges ruled the cases? The government issued a guideline for the

judges how to rule in the court.[2]. This is the famous Dajokan Fukoku 1875

No.8 on Jorii (条理) which said the judges were to rule the cases according to the statutes, if there were no statutes

according to the customs, if there was no custom

according to Jori. Jori could be translated as “reasonable senses” or

“natural law”. But what Jori actually meant was not clear. Many judges

who studied law in the Law School established in the Ministry of Justice where

Gustav Boissonade taught French law were familiar with the concept of natural

law. They thought Jori was the

natural law. Gustav Boissonade was eager to teach natural law in Japan. But other

judges simply understood Jori as the

western legal thoughts.

F.N.[2]

Order of the Dajokan 1875 No.8

(3) The Old Civil Code of Japan

Under the leadership of

Gustav Boissonade who came to Japan as an advisor of the Japanese Government,

the drafting of the Civil Code was accelerated. But it was only in 1890 that

the (Old ) Civil Code was finally promulgated and was to be enforced from 1893.

The Old Civil Cold consisted of 5 parts, Law of Property, Law of Acquirement of

Property, Law of Security, Law of Evidence, Law of Person. Except the Law of

Person and a part of Law of Acquirement of Property (the law of succession) the

Old Civil Code was drafted by Boissonade and translated into Japanese. The Law

of Person and the law of succession were drafted by the Japanese because it was

thought that these areas should consider the Japanese customs and not to be too

much westernized. But also in these areas the influence of Boissonade and

French law was apparent.

After the promulgation of the

Old Civil Code some Japanese scholars and lawyers opposed to the Old Civil Code

from various reasons. A radical opponent of the Old Civil Code Yatsuka Hozumi

wrote in his article a phrase “ Civil Code emerges but the Loyalty dies”. As

the date of enforcement nearing the controversy between the proponents and

opponents of the Civil Code became more and more heated. The Government wanted

to enforce the Civil Code, because the Treaties with the foreign governments

required establishment of legal system including Civil Law Rules as a condition

of abolishing the consular jurisdiction of the foreign governments. The

opponents wanted a place to discuss this problem and appeal to the people. On

February 11 1889 the Constitution of the Japanese Empire was promulgated and

the first National Diet was to be summoned in November 1890. The strategy of

the opponents was to bring the debate in the Diet and to stop or postpone the

enforcement of the Civil Code [4] . After heated debate in May 1892 the law to

postpone the enforcement of the Civil Code passed the Diet. It was to be

postponed until 1896.

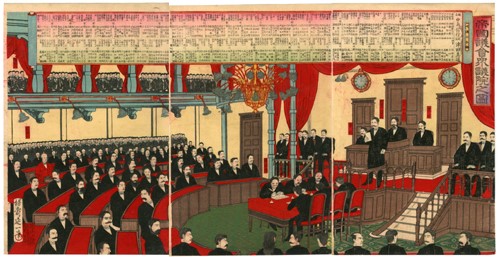

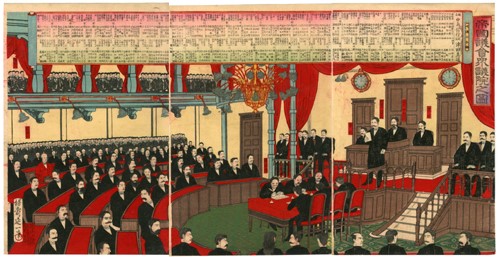

The opening of the first Diet in 1890 (wood print)

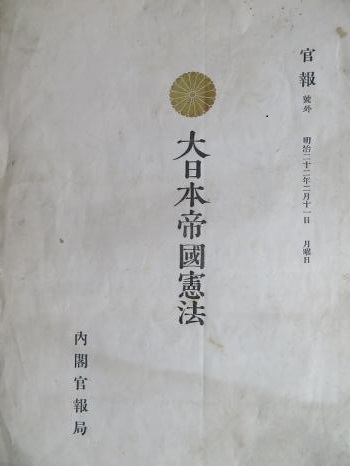

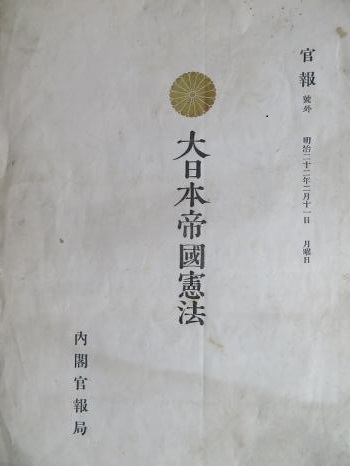

The Official Gazette that promulgated the

Constitution

F.N.[3]

Many foreign lawyers came to Japan as an advisor. They were called Oyatoi

Gaikokujin (the employed foreigners). In the field of law Boissonade from

France and Herman Roesler from Germany were famous. Also Henry Terry from USA

taught Anglo-American law at Tokyo Imperial University. More about Terry see:

Y.Nomi,Terry’s analytical jurisprudence and trust law theory(PDF)

.

[4]

Also the Old Commercial Code by Herman Roesler was the target of the opponents.

(4) The New Civil Code

(a) The Drafters and the Judicial Committee

Thereafter the new drafting

members of the Civil Code were appointed, Kenjiro Ume, Nobushige Hozumi,

Masaakira Tomii. And the Committee to discuss the draft was established.

Ume was a proponent of the enforcement of the Old Civil Code but once the law

to postpone the enforcement had passed the Diet, he worked diligently for the

new draft. He had a profound knowledge of French law, was a docteur en droit of

the University of Lyon. Hozumi studied in England and had the title of

barrister but later moved to Germany and transplanted German elements into the

New Civil Code of Japan. Tomii studied in France but was more sympathetic with

German law.

(b)Popularity of German Law

In the early years of

Meiji French law had a great influence. The Ministry of justice established a

Law School to teach law which was mainly French law. Boissonade was one of the

teacher in this school. His profound knowledge of law had influenced many

Japanese lawyers at that time. The government appreciated Boissonade highly.

But in the 1890s the tide was turning. Now German Law became popular. Why this

change? The reason is not simple. At a political level the government wanted to

follow the German State model, which has defeated France in the 1871 and was

the emerging Empire in Europe under Reichskanzler Bismarck. At a more

theoretical level the German law was thought to be more progressive. One of the

drafters of the New Civil Code Hozumi who studied in the Great Britain was

influenced by social Darwinism. He applied this theory to the development of

law. In his article titled ‘ The Great Revolution in Jurisprudence’ (Hogaku

Kyokai Zasshi, vol 7 no. 6 page 6) Hozumi wrote: We cannot sit

comfortably on the tower of Natural Law. We cannot hold on to the

transcendental idea of justice. What then is the momentum of the revolution of

law? It is the scientific evolution in physics, biology, anthropology,

sociology etc. …..The jurisprudence alone cannot avoid the influence of this

trend. ….The evolution of science in the modern world is so significant. Mr.

Darwin found the great principle of the Natural Selection. Herbert Spencer has

brought one step forward in the Theory of Evolution.

(Apr.2018.to be continued)

II TRUST LAW in JAPAN

A

brief sketch of the trust law in Japan

By Yoshihisa NOMI (31.03.2015)

1 Characteristics of Japanese Trust Law

2006

1.1 Creation of a trust

Trusts in Japan can be

created in three ways. By way of contract, will or declaration of a settler to

become the trustee.

1.1.1 Creation by contract

A trust can be created by a

contract between the settlor and the trustee. This is the most common way of

creating a trust in Japan. There is no special requirements other than the

agreement between the parties for the contract to be effective. A trust

property is necessary for the trust but it does not have to be transferred to

the trustee at the time of the creation of the trust. A trust can be created

without the trust property. Such a contract will bind both parties to perform

their duties. As for the settler, if the property is not transferred at the

time of the contract, he has a duty to transfer the trust property as agreed

between the parties. As for the trustee, he owes a duty of loyalty and other

duties of the trustee even though he has no trust property to manage yet. In

short, trust creation is not a disposal of a property, it is an arrangement.

In a case of a trust of a

land, transfer of the title in the land register is not a prerequisite for the

creation of the trust. It is the general rule of property that the ownership of

a land is transferred between the parties by a simple agreement and

registration is only a requirement to assert the transfer of title against a

third party. This general principle will also be applied to trust creation.

1.1.2 Creation of trust by will

A trust created by will becomes effective at the time of the death of

the settlor. If a certain person is designated in the will as trustee, the

executor of the will or the heirs of the settlor or other interested party

shall call on the person designated as trustee whether he undertakes the trust

or not.

In practice creation of a trust by will is increasing, but not very

much. Because people who are interested in disposing their property after their

death can during their lifetime create a trust inter-vivos with a condition

that the beneficiaries designated in the trust instrument acquire their

beneficial rights only after the death of the settlor. It resembles the

revocable trust in USA, but in Japan the settler does not have a right to

revoke the trust, only a right to change the beneficiaries.

1.1.3 Declaration of trust (self-trust)

Declaration of a trust or a self-trust is a new method of creating

a trust provided by the Trust Act 2006. The settlor declares himself to be the

trustee, though this declaration must be authenticated by a notarial deed. It

is expected to be used in asset securitizations. Also a business corporation

may think it useful to partition its business using self-trust. Using a trust

each division of the business will have a separate patrimony. This method of

trust creation was criticized by specialists of civil procedure that such a

method will make it easy for the settlor to hide his property and fraud the

creditors. I think this accusation is groundless. Besides, fraudulent creation

of trust can be annulled by the creditors of the settlor. In practice

declaration of trust is not used very much.

1.2 Fundamental structure of a trust

1.2.1 Trust property legally separated from trustee’s individual property

A trust property does not have a status of legal entity, nonetheless it is

treated as a separate property from that of the trustee. Thus the creditors of

the trustee cannot reach the trust property to satisfy their claims against the

trustee in person. Trust property will not be involved in a bankrupt of the

trustee.

For the trust property to be treated separate from the trustee’s personal

property, if such property can be registered at the registry, it must have the

registration that the property is held by the trustee as trust property.

1.2.2 Beneficial interest and its nature

The nature of beneficial interest is still theoretically an important

problem, but most of the problems related to the nature of the beneficial

interest is solved by the provisions of the Trust Act.

Article 2 of the Trust Act

defines the beneficial interest as follows; The term "beneficial

interest" as used in this Act means a claim based on the terms of trust

pertaining to the obligation of a trustee to distribute property that is

among trust property to a beneficiary or to make any other distribution

involving the trust property (hereinafter referred to as a "distribution

claim as a beneficiary"), and the right to request a trustee or any

other person to carry out certain acts under the provisions of this Act in

order to secure such a claim. Thus beneficial interest consists of two

elements or two parts. One is the claim against the trustee for distribution of

the trust property. This is not a proprietary right on the trust property,

rather a personal right against the trustee. The other is the right to

supervise the trustee including the right to rescind the trustee’s act

exceeding his power. The Trust Law does not characterize the nature of this

right. Therefore the nature of the beneficial interest as a whole is not clear.

The academics disagree on the nature of the beneficial interest. The majority

characterizes the beneficial interest as a personal claim against the trustee.

But there are some academics who argues that beneficial interest is a real

right restricting the power of the trustee.

1.3 Administration of trust

1.3.1 Trustee’s power

1.3.1.1 Trustee’s power in general

The trustee as the title

holder of the trust property has in general power to manage and dispose the

trust property. But this can be restricted by the trust instrument. The scope

of the trustee’s power is determined by the trust instrument and the provisions

of the Trust Law. Whether a trustee has a power to borrow money for the trust

is determined by the interpretation of the trust instrument. To what extent can

the trustee’s power be limited, whether a “bare trust” is allowed is not clear

under the Japanese Trust Law .

1.3.1.2 Delegation of trustee’s power to a third party

Delegation of the trustee’s

power to a third party was limited under the Trust Act 1922. But the Trust Act

2008 relaxed the rule and now the delegation of trust administration is allowed

even though there is no provision in the trust instrument to allow it, if the

delegation of power to the third party is reasonable in light of the purpose of

the trust.

The relation between the

beneficiary and the third party who is delegated the power from the trustee is

an issue. The Trust Act provides that the third party thus delegated the power

has no direct duty against the beneficiary. The third party has a contractual

duty only against the trustee.

1.3.2 Trustee’s Duties

1.3.2.1 Duty of Loyalty and Conflict of Interest

The Trust Act Article 30 provides the duty of loyalty of the trustee (“A

trustee shall administer trust affairs and conduct any other acts faithfully on

behalf of the beneficiary“). Also certain types of conflicts of interest are

prohibited, such as self-dealing, transaction between two trusts administered

by the same trustee (Art.31), and conduct of the trustee with a third party

competing with the interest of the trust(Art.32).

The trustee’s act

violating the Art.31 (self-dealing etc.) is voidable and is also a ground for

the liability of damages (Art.40). If the trustee’s act is in competition with

the interest of the trust (Art.32), the beneficiary may consider that the said

act has been conducted in the interests of the trust property. This is

so-called the right to intervene. Beneficiary can also claim damages for such

acts.

Violation of duty of

loyalty is in general a ground for damages (Art.40). The Trust Act provides

that if the trustee gained profits by the violation of the duty of loyalty the

amount of the profits gained is to be presumed to the amount of loss to the

trust property. This is functionally a relief of so-called disgorgement of

profits. But because of the Civil Law background of the Japanese Law which does

not acknowledge disgorgement of profits, the Trust Act provides only that “the

gain by the trustee” is “presumed to be the damages” of the trust property.

Therefore, theoretically the trustee can against the claim on disgorgement of

profits defend himself by proving that the actual loss was less than the amount

of profits gained by the trustee.

1.3.2.2 Duty of care

The trustee owes a duty

of care which can be exempt partly but not entirely (Art.29).

The duty of care is

provided as a separate duty from the duty of loyalty. The duty of care focuses

on the damage to the trust property by the trustee’s negligent conduct, but the

duty of loyalty focuses on preventing conflict of interests between the trustee

and the trust property. The effect of the breach of duty of care is damages,

but the breach of duty of loyalty gives a relief of “disgorgement of profits”

gained by the trustee (Art.40).

Some scholars argue

that the duty of loyalty is in nature not different from the duty of care. In

the field of company law where the Company Act provides the duty of loyalty of

directors, the Japanese Supreme Court made a judgement in 1975 saying that the

duty of loyalty is not different from the duty of care, that it is only a

concretization of the duty of care.

In the practice of

trust business, such as in pension trusts or in investment trusts, it is very

common that the settlor of the trust appoints a person (usually investment

advisers) with a power to instruct the trustee in the investment of the trust

property. In that case the trustee has a duty to follow the instruction. The

person with the power of instruction (they are called “investment advisers” or

“investment managers”) orders the trustee how and when to invest the trust

property. One problem related to this structure of trust is the conflict

between the trustee’s duty of care and the duty to follow the instruction of

the investment advisor. What happens to the trustee’s liability if the trustee

followed the inappropriate instruction of the investment adviser? Does it

constitute a breach of the duty of care? Or is the trustee exempt from the duty

of care to the extent that he follows the instruction? Also a related problem

is what would be the duty and liability of an adviser who has power to instruct

the trustee. The adviser is not a “trustee” in the strict sense, but he would

be liable for the negligent instruction. Who can claim damages against the adviser,

the trustee or the beneficiaries?

1.3.3 Expenses of trust administration

Trustees can reimburse

the expenses from the trust property. Before the revision of the Trust Act in

2006 the previous Trust Act allowed the trustee to claim reimbursement not only

from the trust property but also from the beneficiary. This gave rise to a

series of litigation between the trustee and the beneficiary. In the 1990s many

local governments created the so-called land trust in which the local

government transferred their land to the trustee (trust bank) and the trustee

built buildings or other facilities on the land borrowing necessary money for

the construction from other financial institutions. According to the plan the

trust property was to receive income from the tenants of the building and repay

the borrowed money in 20 or 30 years so that at the end of the trust term the

trust property will be constituted of the land and the building without any

debts. But because of the recession the plan did not go well. The trust

property was left with heavy burden of debt. The trustee repaid the borrowed

money and claimed reimbursement from the beneficiary (the trustee is liable

against the trust creditors unless there is an agreement of exemption of the

personal liability of the trustee).The defendant beneficiary argued that there

was a special agreement between the parties that the trustee does not exercise

the right of reimbursement, or that there was a negligence of the trustee in

planning such a land trust. But the courts basically acknowledged the claim of

reimbursement of the trustee. After this experience, the new Trust Act 2006

reexamined the reasonableness of the trustee’s right of reimbursement against

the beneficiary and decided to eliminate the statutory right of the trustee of

the reimbursement against the beneficiary.

The trust banks have not yet accepted land trust under the new Trust Act,

but are considering to accept land trust again with a new structure, that is

the trust banks using the limited liability trusts (the trustee’s liability is

limited to the amount of the trust property. See Art.232) or using a clause to

limited the liability of the trustee when borrowing money from other financial institutions.

1.4 Beneficiary

1.4.1 The Nature of the Beneficial Interest (already explained above)

1.4.2 Acquisition of Beneficial interest

If the settlor and the

beneficiary are different persons, there is a problem of when and how the

person designated as beneficiary in the trust instrument will acquire the

status of beneficiary. In a case of a contract for the benefit of third party,

the third party acquires the right at the time he/she consents to accept the

right. A trust created by a contract is considered to be one type of a contract

for the benefit of third party. But different from the general rules on third

party beneficiary, the Trust Act provides that the person designated as

beneficiary acquires the status of the beneficiary at the time of creation of

the trust.

Under the old Trust Act

in which the beneficiaries were liable for the reimbursement from the trustee,

there was a problem of whether a beneficiary can waive his status of

beneficiary to escape the liability of reimbursement. Under the present Trust

Act beneficiaries are liable against the reimbursement of expenses only when

the beneficiary personally agreed to accept the liability. This agreement is

not a part of the trust instrument. It does not bind the successive

beneficiary.

A trust can be created

with successive beneficiaries. For example, a husband creates a trust

designating his wife as the first beneficiary and if she dies his daughter will

be the next beneficiary etc. There are several problems related to this kind of

trust.

(1)Theoretically, by

designating successive beneficiaries it is possible to create a trust which can

last for several hundred years. The Japanese law does not have the rule of

perpetuity and therefore there is no rule except public policy (Art.90 of the

Civil Code which mollifies the juridical act against good moral and public

order.) to restrict such everlasting trust. But the Trust Act provides

limitation of such trusts. “Article 91 A trust

with provisions that upon the beneficiary's death, the beneficial interest held

by said beneficiary shall be extinguished and another person shall acquire a

new beneficial interest (including provisions that upon the death of the

predecessor beneficiary, another person shall acquire a beneficial interest as

the successor beneficiary) shall be effective, in cases where any beneficiary

who is alive when 30 years have elapsed since the creation of the trust

acquires a beneficial interest pursuant to said provisions, until such

beneficiary dies or until the beneficial interest of such beneficiary is

extinguished.”

(2)Practically, how to

tax such a trust is a very important issue, but I must omit this problem.

(3) If a creation of such a

trust infringes the right of a certain heir who has a legally reserved portion

to the estate of the settlor, the heir with legally reserved portion can claim

for abatement of the trust to the extent necessary to preserve that legally

reserved portion. The problem is the effect of the abatement of the trust. Is

it the creation of the trust itself that is to be nullified or only the acquisition

of the beneficial interest by the beneficiary? In the latter case the trust

remains unaffected and only the beneficial interest would be transferred to the

claimant.

1.4.3 Trust Administrator, Trust Supervisor, Agent of the Beneficiary

In a trust where the

beneficiaries cannot from various reasons protect their own interests it is

necessary to establish a mechanism for the protection of these beneficiaries.

The Japanese Trust Act provides three institutions; trust administrator, trust

supervisor and beneficiary’s agent.

In a trust in which all the

beneficiaries are of future beneficiaries, a trust administrator can be

appointed to protect the interest of the future beneficiaries (Art.123). The

trust administrator has all the powers of a beneficiary and exercise these

rights in its own name but for the benefit of the future beneficiaries.

In a trust where

beneficiaries exist but because they are infants or mentally handicapped and

are difficult to exercise their own right, a trust supervisor can be appointed

for the protection of these beneficiaries (Art.131). Also where the number of

the beneficiaries is large it is sometimes difficult to make a unanimous

decision of the beneficiaries. An appointment of a trust supervisor will in

such a case facilitate decision making of the beneficiaries. If a trust

supervisor is appointed he has the exclusive right and the beneficiaries cannot

exercise their rights. This may be uncomfortable for the beneficiaries who do

not want to hand over all his rights to a trust supervisor. Therefore instead

of appointing a trust supervisor, a beneficiary’s agent can be appointed (Art.

138). Even if an agent is appointed the beneficiaries retain their core

rights.

1.5 Modification, Partition and Merger of trusts

1.6 Termination of a trust

1.7 Special types of trust

1.7.1 Trust without beneficiaries (Art.258)

A trust can be created

for a certain purpose and with no beneficiaries. This is similar to the purpose

trust in UK. It can be created by contract or will, but not by a declaration of

a trust. Because there is no present or future beneficiaries in this type of

trusts, the settlor supervises the trustee instead. It is also possible to

appoint a trust administrator.

The duration period of a

trust without beneficiaries may not exceed 20 years.

1.7.2 Charitable trusts

Charitable trusts are

created by contract or by will, but need approval from the government or from

the local government. The structure of charitable trust is the same with the

trust without beneficiaries. At the time the revision of the trust law was

discussed also a new frame work for charitable organizations was planned in the

government. Because we thought charitable trusts should be under the same

framework for charitable organizations, the provisions on charitable trust were

excluded from the Trust Act 2006 and we waited for the law on charitable

organizations to be enacted. And in the meantime the provisions of the previous

trust act were maintained, though in a separate Act on Charitable Trusts. Now

that the new law for the charitable organizations has been enacted, the

government is planning to reopen the discussion on charitable trusts and

discuss the compatibility with the Trust Act 2006 and the relation to the

governmental approval system for the charitable organizations.

2 Trust Business in Japan

2.1 License for trust business

To do a trust business

the trustee must acquire a license for the trust business provided in the Trust

Business Act. Only stock companies with certain qualification can acquire

license for the trust business. Therefore individuals, partnership and other

type of organizations not in the form of a stock company cannot do trust

business. Trust banks are not trust companies which are given license according

to the Trust Business Act, but are allowed to do trust business by a special

law which allows banks to do trust business.

2.2 Commercial trusts and private trusts

In Japan many scholars

and practitioners use the term commercial trusts and private trusts. Trusts

used in the business is usually referred to as commercial trusts, such as

investment trusts or trusts used in a securitization scheme. And a private

trust is a trust in a family trust or a trust to support disabled individuals.

But as for the duties of the trustee or the rights of the beneficiaries there

is no difference between commercial trust and private trust. In Japan it is

more important to differentiate between trusts to which the Trust Business Act

is applied and trusts to which the Act does not apply. In the former type of

trusts a license of trust business is necessary. From this view point trust it

is appropriate to divided trusts as business trusts and non-business trusts.

For example, if a trustee undertakes a trust for the support of a disabled person

only once and not repeatedly, then this is a non-business private trust for

which a license for business trust is not necessary. But if the same person

undertakes the same kind of trust repeatedly several times, then this is

regarded as doing business and need license for business trust.

2.3 Some examples of trusts used in business

In practice the trusts

banks are the main player as trustee, though a trust company can also undertake

trusts.

Investment trusts,

pension trusts, trusts used in securitization scheme, trusts for the management

of the land, patent trusts, trusts for the support of disabled or mentally

handicapped person, trusts for the wealth transfer to the next generation,

charitable trusts are some example of trusts undertaken by the trust banks.

3

Cases

There

are not many cases which went to the court. The following cases are some of

them.

3.1 Land trust cases

In the 1990s many landowners

made a contract with a trust bank to create the so-called land trust. In a land

trust, (1) the owner of a land transfers the ownership the land to the trustee

to create a trust. (2) The trustee accepts the trust and constructs a

commercial building etc. on the land with money borrowed from other financial

institutions (the trust banks can lend the money to the trust but this was

considered to be a conflict of interest and therefore was avoided). (3) If the

land trust scheme had developed as planned the borrowed money would have been

repaid by the income from the commercial building and after 20 or 30 years the

trust property, now land and the building, would have returned to the settlor

or the beneficiary. But because of the recession the trust property did not

yield enough money for the repayment. Instead the trustee repaid the borrowed

money from its own pocket. (4) And trustee claimed reimbursement of these

expenses from the beneficiary. In these cases the old Trust Act 1922 was

applied. The Trust Act had a provision which allowed the trustee to claim

reimbursement of expenses against the beneficiaries.

In many of these

lawsuits actually the local governments were the settlor/ beneficiary and

became the defendants of the lawsuit. They argued that there was a special

agreement between the parties to exclude the trustee’s right of reimbursement.

But the courts acknowledged the trustee’s claim for reimbursement.

Under the new Trust Act an

individual agreement between the trustee and the beneficiary is necessary for

the reimbursement against the beneficiary.

3.2 Set-off

In Japan the trustee (a

trust bank) often lends money to the beneficiary. In a case of non-performance

of repayment by the beneficiary the trustee may seek to set off its obligation

to distribute trust property against the debt of the beneficiary. Whether to

allow such a set off was an issue in the lower courts.

Lower courts’ decisions

are divided in whether to allow the set off between these debts. Majority of

the academics allow the set off. They argue that if the beneficiary’s claim

against the trustee for distribution of trust property is in money, the

trustee’s debt and the beneficiary’s debt are of the same kind and therefore

the requirement of mutuality is met. Against this opinion some scholars

criticize that the trustee refusing to perform its obligation to distribute the

trust property to the beneficiary and instead claiming set off to satisfy

trustee’s own credit is against the duty of loyalty.

Similar problem arises

when the trustee creates pledge over the beneficial interest to secure its

credit against the beneficiary. The majority of academics consider that

creation of such a pledge and exercise of the pledge is not against the duty of

loyalty of the trustee.

3.3 Inappropriate instructions of the investment adviser and the trustee’s

duty of care

In investment trusts it

is common that an investment advisor is appointed by the settlor and the

trustee is to follow the instruction of the investment advisor. If such a

scheme is created by the trust instrument it the duty of the trustee to follow

the instruction of the investment advisor. The problem arises when the

instruction is inappropriate and will damage the value of the trust property.

Should the trustee reject the instruction of the investment advisor or follow

it? This is a problem of the scope of the duty of care of the trustee. Several

lawsuits were filed before the court but have not yet come to any conclusion.

4

Some fundamental theoretical problems

4.1 Compatibility of trust in the Civil Law System or the Nature of

Beneficial Interest

As already mentioned above the nature of the beneficial interest is the

core problem to understand trust. The majority of the academics characterize

beneficial interest as personal right against the trustee. But if so, how do we

explain the beneficiary’s right to rescind the transaction of the trustee which

does not fall within the scope of the trustee’s power and recover the property

from the third party? If the trustee has the title or the ownership of the

trust property what is meaning of the restraint to the trustee’s power over the

trust property?

And why does the beneficial

interest reflect the changes and fluctuation of the trust property? For

example, if the trust property increases the beneficial interest will also

increase.

All these phenomena

cannot be comfortably explained from beneficial interest=personal right

doctrine. But most of these problems are solved by the provisions in the Trust

Act, so that these questions, still important for the academics, are only of

theoretical nature.

4.2

Is a trust a contract?

Different from the

Anglo-American understanding of trust, under the Japanese law a trust created

by the settlor and the trustee is a contract. The existence of the trust

property is not necessary at the time of concluding a trust contract. Though the

majority of the academics understands that trust property is essential for the

trust so that at some point property must be transferred from the settlor to

create the trust property. But some academics goes further that trust property

is not essential for a trust. For example, a trust created without any initial

trust property can still borrow money from the third party if the trustee

guarantees the repayment. The borrowed money will constitute the trust

property. The trust will use this money for investment or to do business etc.

If this kind of trust is allowed trust becomes one step closer to a

corporation.

Another problem

discussed in the context of trust and contract is the nature of the duty of the

trustee. If a trust is a contract it is possible to exempt the trustee from its

duties. It is possible to opt out all the duty of loyalty or the duty of care

be a contractual agreement. If not how do we explain the limitation of freedom

of contract in a trust?

4.3 How do we explain the trust property being separated from the trustee’s

individual property?

Trust is not a legal entity

but the trust property is treated as a separate property from trustee’s

individual property. The French trust law or the Trust Law in Quebec explain

this with the notion of patrimony. A trust creates a separate patrimony. In

Japan there is no theoretical explanation. How to explain the nature of trust

property is a headache in Japanese Law.

4.4 Trust law rules vs Law of succession

Trusts create a tension

with the Law of Succession. The Trust Act 2006 allows the so-called successive

beneficiaries. A difficult problem arises when the beneficial interest of the

first beneficiary ends at his/her death and at the same time the second

beneficiary acquires his/her beneficial interest. The beneficial interest of

the second beneficiary will end at time of his/her death and at this point the

third beneficiary acquires his/her beneficial interest and so on. The Law of

Succession does not allow such kind of successive legatee or devisee. But using

trust the settlor can circumvent the restriction of the Law of Succession. The

trust lawyers explain that beneficiary and legatee/devisee are different and

therefore different rules are to be applied. But some specialist of Civil Law

strongly oppose to the rule provided in the Trust Act.