-Practice the English Copy-Writing Metod Every Day ⑦ 2013年2月 志村英盛

関連サイト:英語脳創りで情報力・発信力を高める-毎日、量聴、量作文、量音読

061

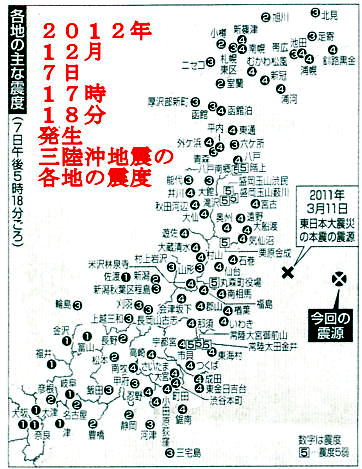

Strong earthquake strikes off

northeastern Japan

December 07, 2012

A magnitude-7.3 earthquake struck off the coast of northeastern Japan

in the same region that was hit by a massive earthquake and tsunami

last year. Tokyo high-rises swayed for minutes, one city reported

a small tsunami and at least two people were reported injured.

The Japan Meteorological Agency said the earthquake had a preliminary

magnitude of 7.3 and struck in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of

Miyagi prefecture at 5:18 p.m. on Dec. 7. The epicenter was 10 kilometers

beneath the seabed and 240 kilometers offshore.

The tsunami warning was issued for Miyagi Prefecture, while tsunami

advisories were issued for the prefectures of Aomori, Iwate, Fukushima

and Ibaraki. The warning and advisories were canceled at 7:20 p.m.

There were no immediate reports of injuries from the earthquake

and tsunami or structural damage.

According to the Nuclear Regulation Authority, no reports had been

submitted about problems at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant,

operated by Tokyo Electric Power Co., the Onagawa nuclear power plant,

operated by Tohoku Electric Power Co., or the Tokai No. 2 nuclear

power plant, operated by Japan Atomic Power Co.

TEPCO officials held a news conference and said there were

no irregularities at the Fukushima No. 1 or No. 2 nuclear plants.

Monitoring posts also did not detect any unusually high radiation

readings.

The Nuclear Regulation Authority also said there were no problems

at the nuclear fuel reprocessing facility at Rokkasho, Aomori Prefecture,

operated by Japan Nuclear Fuel Ltd.

After the quake, which caused buildings in Tokyo to sway for

at least a minute, authorities issued a warning that a tsunami

potentially as high as 2 meters could hit. Ishinomaki, a city in Miyagi,

reported that a tsunami of 1 meter hit at 6:02 p.m.

Miyagi prefectural police said there were no immediate reports of

damage or injuries, although traffic was being stopped in some places

to check on roads.

Shortly before the earthquake struck, NHK television broke off

regular programming to warn that a strong quake was due to hit.

Afterward, the announcer repeatedly urged all near the coast

to flee to higher ground.

The quake and tsunami warning forced Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda

to cancel campaigning in Tokyo ahead of a Dec. 16 election.

Noda was on his way back to his office, but there was no immediate plan

to hold a special Cabinet meeting.

Public spending on quake-proofing buildings is a big election issue.

Phone lines were overloaded, and it was difficult to contact residents

in Miyagi.“Owing to the recent earthquake, phone lines are very busy,

please try again later,” the telephone operator said.

The End

062

New measures to inspect aging tunnels

came too late for fatal site

Dec.3,2012

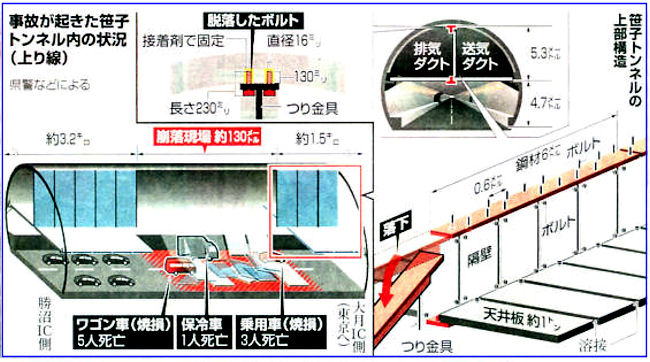

The fatal cave-in of ceilings inside a Chuo Expressway tunnel

in Yamanashi Prefecture on Dec. 2 occurred just after

its operator Central Nippon Expressway Co. (NEXCO Central) and

two other expressway companies started looking at measures

to inspect and repair aging roads last month.

Experts pointed to the possibility of aging as the cause of

the accident at the Sasago Tunnel in Otsuki, which left

nine people dead, and called for a review of inspection methods

and early detection of the cause of the accident.

According to NEXCO Central, the 4,784-meter Sasago Tunnel,

whose service commenced on Dec. 20, 1977, is located 82.7 kilometers

from the Takaido Interchange in Tokyo's Suginami Ward,

which is the starting point of the Chuo Expressway.

Each of the precast-concrete ceiling panels that fell off

inside the tunnel over an approximately 130-meter section measured

5 meters in width, 1.2 meters in depth, 8-9 centimeters in thickness

and weighed some 1.2-1.4 metric tons.

The ceiling boards are placed on the right and left sides

of the tunnel, with their ends fixed to the tunnel walls and

the central part fixed to metal fittings hanging from the top

of the tunnel.

The metal fittings are placed at an interval of 1.2 meters

-- the same as the depth of each ceiling board -- and partition walls

are set between those fittings, dividing the space above the ceiling

boards into right and left. One of the partitioned spaces is

for ventilating exhaust gases and the other is for supplying fresh air

into the tunnel, comprising the so-called transverse ventilation system.

In the accident, the metal fittings also fell off while the ends

of the ceiling boards were still fixed to tunnel walls, causing

a V-shaped cave-in.

The construction of the tunnel was undertaken by a consortium

of Taisei Corp. and Obayashi Corp. between August 1976 and September 1977,

with Central Nippon Highway Engineering Tokyo Co. taking on inspection

work thereafter.

According to Central Nippon Highway Engineering Tokyo, technical

experts regularly conducted visual checks and hammering tests

on the tunnel's ceilings. "Experts can estimate to a certain degree

whether the equipment is deteriorated or not based on the hammering

sound and reactions," one company official explained.

"Hammering tests are the most reliable method and are applied

to other tunnels and used by other contractors as well."

In recent years, however, the longitudinal ventilation system

-- which is free of ceiling boards and can ventilate with jet fans

and the movement of cars -- has become mainstream due to its low cost.

The transverse ventilation system, on the other hand, is more costly

with more structural objects needed.

"Although we weren't planning to update the tunnel, we'd thought

the longitudinal ventilation system was better in terms of cost

and because the ceiling boards (in the transverse ventilation system)

give drivers a sense of pressure. However, it's not easy to replace

the system because tunnels need to be closed to traffic for a long

period of time for the work," said a NEXCO Central official.

The End

063

Fat and Happy

from Beating Japan

by Francis McInerney and Sean White

The old Soviet Union's central planning organization,

Gosplan, could have taught Japan Inc. a few things about

stream-lined bureaucracy.

From headquarters in Tokyo, layer after layer of management

masterminds Japan Inc.'s every step. Somehow, the process works

in Japan. Personal networking can overcome organizational

complexity to serve Japanese customers.

Said Guy de Jonquieres in the Financial Times,

"To the western eye, the system may appear inefficient because

it occupies so many people. It works because it encourages highly

efficient diffusion of information. Not only do face-to-face

communications at every stage of product development forge

close links between different corporate functions, regular rotation

of staff ensures that all concerned understand each other's jobs.

"That's great in Japan. Unfortunately, overseas managers and

their customers are simply excluded from the process.

Companies exclude customers at their peril.

We have seen Japanese companies with as many as ten layers

between frontline employees and the CEO. Sometimes these layers

are triplicated, once in the U.S. holding company,

again in the Japanese line division,

and finally in the Japanese regional marketing organization.

In such a case, for example, a computer disk drive salesman

in Atlanta who has a request from a customer that requires

a change in the product would send a memo to the disk drive

division in suburban Tokyo. At the same time, the sales rep would

copy his memo to the North American marketing group at headquarters

in downtown Tokyo. The disk drive engineering and manufacturing

managers then study the feasibility of the request, since they

would have to make any changes in the product that are ultimately

required.

Within this line organization, an endless number of meetings

between managers, market planners, development engineers, and

product engineers takes place, each generating further meetings

and studies. The headquarters marketing people, with a disk drive

sales quota for North America to meet, analyze the market potential

of a product change and keep tabs on the disk drive line people

to make sure the request doesn't get swept under the carpet.

Meanwhile, the U.S. holding company management could get

dragged in if the change has an effect on another division or

raises legal or regulatory questions.

Confused ? Imagine how the poor salesman feels six months

after making his request. Customers, however, are not confused

by all this - they have long since moved on to another supplier.

Examples like this are not only real but common in Japanese

companies. Ironically, if the customer were in Japan,

the organization would work well, expanding and contracting

organically to meet the needs of customers, who are close at hand

(particularly big government customers and other buyers

from the keiretsu).

To control overseas operations while meeting the number one goal

of leaving cozy relations at home intact, complex matrix structures

are required. When confronted with elaborate, multilayered,

three-dimensional organization charts, Japanese executives will retort

that these charts don't reflect the real links that connect real

decision-makers. They are right: often as not, you can circle

the University of Tokyo graduates and draw lines between them

to see where the real power flows.

Unfortunately, none of their overseas employees or customers are

likely to be Todai grads, and so are off the power grid.

Competitors willing to flatten their own organizations and decentralize

decision-making can run circles around such Byzantine bureaucracies.

Of course, the Japanese do not have a monopoly on bureaucracy.

AT&T's notorious failure in computers can be traced to the extraordinary

number of layers of management between customers and decision-makers.

AT&T tried to solve its problem in computers by acquiring NCR,

avoiding the root cause of its woes. For too long, General Motors

refused to deal with the layers of management that make the company

inward-looking and all but oblivious to the needs of its customers,

preferring to hack away at the factories and blue-collar workers

who got left holding the bag.

The main purpose of the bureaucratic ramparts at GM was to protect

top management from the assaults of customers and shareholders.

And IBM continued to push all important decisions up to its celebrated

management committee at the top of the huge Big Blue bureaucracy

long after it was clear that IBM's agenda and not that of its customers

was being served.

One expensive example: IBM thought that it could rejuvenate its

mainframe business by making PCs into perfect mainframe access points;

the result was OS/2, a new generation of PC software perfectly designed

to solve IBM's problem. Selling OS/2 to other customers has proved

a big challenge.

To deal with its own inefficiencies, the bureaucratic morass

in Japan grows and grows. Teams of managers study information

about overseas markets, without ever actually talking to overseas

customers. As one Japanese executive said to us, "the biggest

problem in our company is that we have too many general managers."

Meanwhile, salesmen in the field methodically gather from customers

information which is carefully transmitted in detailed memos back

to headquarters, where it disappears, as light into a black hole

at the center of some distant galaxy, never to be seen again.

In one company we looked at, the salesmen on the ground in the States

were patching together account plans from out-of-date press releases,

newspaper clippings, and handwritten notes. Meanwhile, the market

planners in Tokyo had detail on customers in the United States

that would make the NSA blush. But this bureaucracy was not supporting

sales; quite the reverse.

Most American businesses once worked this way, but competitive

pressures during the 1980s -largely from Japan - forced American

industry to thin or eliminate layers of middle management.

By the early 1990s, even the biggest and most successful companies

in America, like AT&T and GM, finally had to face 'fully the horrors

of these irresistible pressures. Throughout America, the process

continues, as layoff after layoff decimates the ranks of white-collar

workers.

Japan's middle managers have been spared such restructuring.

Flush with cash from the appreciation of the yen in the mid-eighties,

Japan spent its way to growth. As with carpet bombing, however,

occasionally you hit something strategic. Successes are in spite of

decisions laboriously made in Tokyo, not because of them.

While in the United States "fat and happy" now means

"dead and gone," in Europe government-sponsored industrial

policies encourage mergers and consolidations to keep

the bureaucratic dinosaurs alive. Europe will probably take longer

to face the music than even Japan.

With a degree of wishful thinking that can only be called

inspirational, former Prime Minister Edith Cresson of France decided

in 1991 to combine state-owned nuclear power, biotechnology, and

information technology into one high-tech powerhouse.

Colbert would be proud. By contrast, Japan's Asian competitors

are not living in a dream world. Change may be coming to

the companies from which Japan has the most to fear.

Daewoo, a diversified Korean conglomerate with its sights set

on information technology, fired a third of its middle managers

in 1991 to speed up decision-making.

Japan cannot resist this tide of change.

Honda, for one, has tried to come to terms with its own bureaucracy.

Honda was a superstar of the 1980s, but its growth slowed dramatically

in the early 1990s, forcing the company to admit that it could not act

fast enough. Consensus decision-making was resulting in

designed-by-committee cars that were boring. Honda will now make managers

individually, not collectively, responsible for their operations.

Layers of management will be reduced. Honda is on the right track,

but there is little indication it is transferring real power

to the United States, where most of its sales are. Nevertheless,

this change is bad news for American competitors.

During the 1990s, the swollen ranks of Japanese corporate management

will break under the pressure. As Japan invests and manufactures overseas,

the inadequacies in its current management structure, designed for export,

will become ever more apparent. At the same time, the postwar era of

the great Japanese industrialists - like Shoichiro Honda of Honda Motor Co.,

Konosuke Matsushita of Matsushita Electrical Industrial Co.,

Koji Kobayashi of NEC Corp., and Akio Morita of Sony Corp. - is rapidly

coming to an end. Once these single-minded visionaries are gone

from the scene, the faceless, soulless bureaucracies must take over.

The transition will not be easy; the sheer willpower of these men,

which drove their companies forward, will disappear. Such change is

ongoing in the United States (as everywhere else).

DEC, for example, faces the retirement of Ken Olsen, a real leader

who has driven product development at DEC since day one.

But the United States made the big transition from the rule of

the great entrepreneur-industrialists -when the likes of Alfred Sloan

at GM, Thomas Watson at IBM, and J. P. Morgan reigned supreme -

to one of professional management during the immediate postwar period,

a time when its place in the world was unchallenged.

Japan will enjoy no such luxury. Bureaucracies - Japanese or otherwise

- insulate decision-makers from customers. In the bad old days,

suppliers could get away with such inefficiencies because they held

all the cards.

Governments could be counted on to stack the deck in favor of

business, especially national champions. Today, especially in America,

the customers hold all the cards, and they are aces.

The End

064

Potsdam Declaration

-Proclamation Defining Terms

for Japanese Surrender

Issued at Potsdam, July 26, 1945

(1)

We ? the President of the United States,

the President of the National Government of the Republic of China, and

the Prime Minister of Great Britain,

representing the hundreds of millions of our countrymen,

have conferred and agree that

Japan shall be given an opportunity to end this war.

(2)

The prodigious land, sea and air forces of the United States,

the British Empire and of China,

many times reinforced by their armies and air fleets from the west,

are poised to strike the final blows upon Japan.

This military power is sustained and inspired by the determination

of all the Allied Nations to prosecute the war against Japan

until she ceases to resist.

(3)

The result of the futile and senseless German resistance

to the might of the aroused free peoples of the world stands forth

in awful clarity as an example to the people of Japan.

The might that now converges on Japan is immeasurably greater

than that which, when applied to the resisting Nazis,

necessarily laid waste to the lands, the industry

and the method of life of the whole German people.

The full application of our military power, backed by our resolve,

will mean the inevitable and complete destruction of

the Japanese armed forces and just as inevitably

the utter devastation of the Japanese homeland.

(4)

The time has come for Japan to decide whether she will continue

to be controlled by those self-willed militaristic advisers

whose unintelligent calculations have brought the Empire of Japan

to the threshold of annihilation,

or whether she will follow the path of reason.

(5)

Following are our terms.

We will not deviate from them.

There are no alternatives.

We shall brook no delay.

(6)

There must be eliminated for all time the authority and

influence of those who have deceived and misled the people of Japan

into embarking on world conquest,

for we insist that a new order of peace, security and justice

will be impossible until irresponsible militarism is driven from the world.

(7)

Until such a new order is established and

until there is convincing proof that

Japan’s war-making power is destroyed,

points in Japanese territory to be designated

by the Allies shall be occupied to secure the achievement of

the basic objectives we are here setting forth.

(8)

The terms of the Cairo Declaration shall be carried out and

Japanese sovereignty shall be limited to the islands of Honshu,

Hokkaido, Kyushu, Shikoku and such minor islands as we determine.

(9)

The Japanese military forces, after being completely disarmed,

shall be permitted to return to their homes

with the opportunity to lead peaceful and productive lives.

(10)

We do not intend that the Japanese shall be enslaved as a race

or destroyed as a nation, but stern justice shall be meted out

to all war criminals, including those who have visited cruelties

upon our prisoners.

The Japanese Government shall remove all obstacles to the revival

and strengthening of democratic tendencies among the Japanese people.

Freedom of speech, of religion, and of thought, as well as respect

for the fundamental human rights shall be established.

(11)

Japan shall be permitted to maintain such industries as will sustain

her economy and permit the exaction of just reparations in kind,

but not those which would enable her to re-arm for war.

To this end, access to, as distinguished from control of,

raw materials shall be permitted. Eventual Japanese participation

in world trade relations shall be permitted.

(12)

The occupying forces of the Allies shall be withdrawn from Japan

as soon as these objectives have been accomplished

and there has been established in accordance with

the freely expressed will of the Japanese people

a peacefully inclined and responsible government.

(13)

We call upon the government of Japan to proclaim now

the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces,

and to provide proper and adequate assurances of their good faith

in such action.

The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.

The End

065

An overview of Japan's wars

in the Showa Era

by YOMIURI SHIMBUN

Manchuria - start of the slide into war

More than 60 years have passed since Japan's surrender

to the Allied Powers.

The responsibility for waging the war was dealt with

by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East,

known as the Tokyo Tribunal.

The manner and circumstances in which the tribunal was administered

has long attracted criticism and its verdicts were not those of

the Japanese people.

Now is the time to reexamine the miseries of the war on Japan's own

and to identify the responsibility of the war era's political and

military leaders for their failure to avoid war.

To address this task, the Yomiuri Shimbun established an in-house

investigative panel, the War Responsibility Reexamination Committee,

comprised of members of the newspapers Editorial Board,

the Yomiuri Research Institute and senior writers from a range of

departments of the Editorial Bureau.

The outcome of this protect, undertaken by the team in collaboration

with experts from Outside the Yomiuri Shimbun, was originally published

in a 27-installment series in the newspaper between August 2005 and

August 2006.

Looking back now at the wars of the Showa Era (1926-89),

there arise a number of problems and doubts.

These can be divided into five broad questions in connection

with the Yomiuri Shimbun committee's quest concerning war responsibility:

①

Why did Japan extend the lines of battle following the 1931

Manchurian Incident, plunging the country into the quagmire of

the Sino-Japanese War ?

②

Why did Japan go to war with the United States in spite of extremely

slim prospects for victory ?

③

Shortly after victories in the initial phase of the Pacific War,

what foolishness caused the Japanese military to employ' banzai attacks,'

to command its soldiers and sailors to die-but-never-surrender, and

to resort to"kamikaze' suicide aircraft attacks after the rapid

deterioration of Japan's position ?

④

Were suffident efforts made to bring the war to an end and

was it possible to prevent the civilian devastation caused

by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ?

⑤

What were the problems with the Tokyo Tribunal in which

the Allied Powers tried Japanese political and military leaders

charged with war crimes ?

On September 18, 1931, the tracks of the South Manchurian Railway

Company's (Mantetsu) line were pounded with bombs at Liutiaohu

in the suburbs of Mukden (now Shenyang) in northeast China.

A group of high-ranking Officers of the Kwantung Army,

Japan's field army in Manchuria, including Senior Staff Officer

Seishiro Itagaki and Operations Officer Kanji Ishihara,

were responsible for plotting an explosion that would mark

the beginning of the Manchurian Incident -the conquest of Manchuna

by the Kwantung Army.

The Cabinet at that time, headed by Prime Minister Reijiro Wakatsuki,

was deeply alarmed by the incident and initially adopted a policy of

localizing the affair.

The Wakatsuki administration, however, was unable to hold in check

the intensification of military operations by the Kwantung Army and

proved to be incapable of bringing the Army under control.

The Manchurian Incident, coupled with the 1932 establishment of

a puppet state - Manchukuo -by the Kwantung Army, constituted

the start of Japan's international isolation.

Why were the government and the upper echelons of the military

in Tokyo unable to halt reckless acts perpetrated by the Kwanrung Army ?

It is worth noting that at the time Japan had an array of rights and

interests, such as Mantetsu in Manchuria, that had been acquired as

the result of Japan's victory in the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese War and

other armed conflicts.

Ishihara and his Army allies espoused the theory that Japan must

prepare for a "final war" with the United States and the Soviet Union

by harnessing natural resources from Manchua and Inner Mongolia.

In December 1931, the League of Nations formed the Lytton

Commission to determine the causes of Japan's military campaigns

in Manchuria following the railway bombing near Mukden.

Rejecting Japan's claim that the incident was in self-defense,

the five-member commission released the Lytton Report in October 1932,

denouncing the Manchurian Incident as an act of aggression by Japan.

In March 1933, following the adoption of the Lytton Report

by the General Assembly of the Leagued Nations In February,

Japan announced its withdrawal from the world body.

In an attempt to keep its interests in Manchuria intact,

Japan began the North China Separation Operation, aimed at bringing

part of northern China under Japanese control.

The operation, however, only served to add fuel to China's armed

resistance.

On July 7,1937, a clash between Chinese and Japanese troops

known as the Marco Polo Bridge (Lugougiao) Incident took place

on the outskirts of Beijing and triggered the full-scale phase of

the Sino-Japanese war.

In the early stages of the 1937-45 war, Japanese troops occupied

Nanjing, giving rise to the incident known as the 'Nankin Gyakumini

in Japanese and the "Rape of Nanking" abroad that took place between

December 1937 and January 1938. There remain disputing views

over how many Chinese were killed in the incident.

Unable to come up with a plan for peace negotiations, the then

cabinet, headed by Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, kept hesitating.

The Konoe Cabinet finally issued a statement declaring

japan was determined "never to consider the Nationalist (Kuomintang

government of China) as Japan's negotiatng partner."

Aims of war ill-defined

Japans national purposes for engaging in the war with China

were unclear.

A government statement issued in August 1937 said the war was

designed to "punish acts of violence committed by Chinese troops."

In November 1938, the second Konoe Cabinet issued a statement

that set the goal of the war as establishing a "New Order in East

Asia."

It is widely considered today, however, that the statement

by the Konoe Cainet was nothing but an ill-grounded cover for

glossing over Japan's bid to acquire political and economic dominance

over China.

Why was the extension of the boundaries of the Sino-Japanese War

left unchecked ? This Is a question of crucial importance

in reexamining the processes that led to the Pacific War.

In developments after the Manchurian Incident, the Japanese

military continuedued to intervene in politics.

In the wake of two coup d'etat attempts by groups of Imperial

Japanese Army officers in 1931, there were a spate of assassinations

in February and March 1932 of influential polibcal and business

leaders in what became known as the League of Blood Incident.

On May 15, 1932, a group of Imperial Japanese Navy officers broke

into the official residence of then Prime Minister Tsuyoshi Inukai

and shot him to death.

Of particular significance to the rise of militarism was a coup

d'etat attempt by a group of radical young officers of the Imperial

Army on February 26. 1936.

The rebels temporarily seized the heart of Tokyo, killing major

figures such as Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal Makoto Saito and

Finance Minister Korekiyo Takahashi.

The event, known as the February 26 (2/26) Incident, was organized

by a faction of officers called the Kodo-ha (Imperial Way Faction),

which was replaced after the incident by its rival faction,

the Tosei-ha (Control Faction), which aimed to consolidate the leadership

of the military establishment.

Such developments are considered to have paved the way for

the nefarious tendency toward influencing politics by means of terrorism.

They resulted in an end to government based on party politics,

and movements calling for a "one nation, one party" system gained ground.

In 1940. a tbtallmrian organization, Taisei Yokusan-kai (Imperial Rule

Assistance Association), was founded, leaving the Diet utterly powerless.

Even before coming under military-imposed censorship, newspapers

at the time played a key role in instigating Japan's move toward war

in the Manchurian Incident.

In this respect, the Japanese mass media should not be excluded

from responsibility for helping encourage the emergence of militarism.

Three mistakes lead to war with U.S.

Japan misread the prevailing international situation in 1941

when it went to war against the United States.

Its first mistake was its alliance with Germany and Italy

that was concluded in September 1940 by Prime Minister

Fumimaro Konoe's second Cabinet.

By this time, Germany had invaded Poland, an attack that erupted

into World War Ⅱ, ultimately pitting the United States and Britain

against Germany and Italy.

However, Japanese Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka insisted

that if the three Axis nations joined forces with the Soviet Union,

the United States would be discouraged from entering the war.

Naval leaders - Mitsumasa Yonai, Isoroku Yamamoto and

Shigeyoshi Inoue - initially opposed the allaiance, but many other naval

officials wanted to advance into Southeast Asia.

This sentiment prompted the Imperial Japanese Nary to support

the alliance. Some observers argued, therefore, that the much-touted

public perception that the Nary opposed going to war with Britain

and the United States was wrong. Saying that it was the greatest

mistake of his life, Matsuoka later regretted having concluded

the Tripartite Alliance !

Japan's second blunder was the order by Konoe's third Cabinet

in July 1941 to advance into Indochina.

Japan and the United States were holding talks to avoid war

at the time. Japan proposed halting its advance into Southeast

Asian countries and pulling out of some areas in China.

But Germanys invasion of the Soviet Union led Japan to continue

its advance.

Washington froze Japan's assets in the United States as a warning

to Tokyo, but the Cabinet decided to move south anyway, an action

that restdted in a U.S. ban on oil exports to Japan.

Japan's final mistake made in the lead-up to the Pacific War

was a conference held on September 16, 1941, which was attended

by Emperor Showa.

Konoe was exploring the feasibility of talks with U.S. President

Franklin D. Roosevelt to avert war, but at the conference,

he unilaterally set a dead-line and decided that Japan would go to

war against the United States if negotiations failed.

During the Sino-Japanese War until briefly before the Pacific War,

Konoe was at the center of power for four years.

He was popular, but he did not have a finn support base and was

subsequently criticized for populism.

Hideki Tojo, who succeeded Konoe as Prime Minister, and the other

war-time Prime Ministers have to be held accountable as leaders

during the war.

Tojo, War Minister in the Konoe Cabinet, repeatedly refused U.S.

demands to pull out of China.

After Konoe stepped down, Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo continued

negotiatons with the United States.

The Hull Note, a proposal made by then U.S. Secretary of State

Cordell Hull which Japan regarded as an ultimatum demanding that it

withdraw from Indochina and China, was also a significant factor.

In addition to holding the posts of War and Home Affairs Ministers,

Tojo also served as the Chief of Army General Staff and thus wielded

tremendous power in mobilizing the public for Japan's war efforts.

War fought with an 'armchair plan'

Once a country engages in a war, it must discuss how and when

to exit from hostilities. How did Japan envisage it might end

the Pacific War ?

A war strategy document was drawn up by the Imperial Headquarters-

Government Liaison Conference immediately before the war.

The document outlined the military's rather self-serving plan

to speed up the end of the war against Britain, Chiang Kai-shek

(then leader of China), the Netherlands and the United States.

The document argued that the military should destroy the British,

Dutch and U.S. strongholds in the Far East and establish a system

of salf-sufficiency and self-defense.

Second,the strategy called for areas under Japan's control

to be expanded to push Chiang Kai-shek to step down from power.

Third, it called for Japan to work with Germany and Italy

to force Britain into submission and to discourage the United States

from continuing with the war.

Based only on such a haphazard plan, the government and japan's

Imperial Headquarters went to war against the United States

despite its overwhelming war fighting capacity.

Moreover, initial successes in the war deluded Japan into

overestimating its potential and to expand the front beyond

Japan's geogaphlcal ability to maintain its own strength.

The Guadalcanal campaign, which began in August 1942

on the southernmost end of the Solomon Islands, was nothing

but a tragedy born in a war fought without strategy.

The Imperial Japanese Navy was building an airfield

on the island as a front-line base for dividing U.S. and

Australian forces when U.S. troops mounted a full-scale offensive.

But the Imperial Headquarters made the mistake of sending

small units of troops into battle one after another, only to

have each routed by U.S. troops. The biggest factor in Japan's

defeat at Guadalcanal was its inability to transport enough

troops and supplies to the island.

Following the crushing defeat in the Battle of Midway

in June 1942,Japan gradually began losing control of the seas

in the Pacific.

Cleverly severing Japan's supply routes one by one,

the U.S. forces seized the islands that were Japan's strategic

points one after another as if they were stepping stones.

Of more than 20,000 Japanese troops who died in the Battle

of Guadalcanal, 15,000 are believed to have died of

starvation or illness.

Despite the deteriorating war situation, the Imperial

Headquarters failed to advise the government of the details

of the operation, shieldng themselves behind the independence

of the supreme command. They also concealed unfavorable

information from the public when reporting the war.

There had been an idea of "an absolute defense area" -

selected zones in the Pacific that must be protected at all costs

in the downsized battle front - but the whole idea turned out

to be no more than an armchair plan.

In May 1943 on Attu, part of the Aleutian Islands,

the first contingent of troops was wiped out in a battle

described as an "honorable defeat."

About 2,500 troops left on the island ran out of ammunition.

Instead of sending more troops in support, the Imperial

Headquarters wired Attu, "When it comes to the end,

we hope you will gracefully choose honorable deaths,

with determination to show the flower of the spirit of

Imperial military personnel."

The U.S.forces appealed to the soldiers to surrender,

but the Japanese soldiers charged forward to their deaths,

binding each others'legs together with rope so that no one

could hesitate.

In July 1944,troops in Saipan chose a similar fate.

And the government and the Imperial Headquarters began

ordering airmen to carry out suicide attack with planes

on enemy ships

without trying to bring about the end of the war.

The End

066

JAPAN'S WAR PLAN

from The Effect of Strategic Bombing

on Japan’s War Economy

by United States Strategic Bombing Survey

Japan's decision to go to war with the United States

and the war plan upon which it counted to achieve

its objectives can be understood only in the light

of the background sketched above.

The tradition of success, with limited commitments,

the imminence of Germany's victory on the European Continent

- these counted for more in the minds of Japan's war planners

than any careful balancing of Nipponese and American war potentials.

Above all, they biased the thinking of the high command

toward the notion that the war would not be a lengthy enterprise.

Total war, annihilation of the enemy,

and occupation of the United States

never entered the planning of the Japanese military.

One or two crucial battles were expected to determine

the outcome of the conflict.

The Pacific war, was to follow the pattern set

by the Russian-Japanese hostilities in 1905.

A terrific blow at Pearl Harbor would inflict

a disastrous Cannae on the American Pacific fleet.

Combined with Russia's defeat and England's inevitable doom,

this would assure American willingness to enter peace negotiations.

A settlement satisfying most Japanese demands

would be in sight within 6 months.

The End

067

The Lytton Report

LEAGUE OF NATIONS ASSEMBLY REPORT

ON THE SINO-JAPANESE DISPUTE

The following report was adopted by the Assembly

on February 24th, 1933.

REPORT

The Assembly, in view of the failure of the efforts

which, under Article 15, paragraph 3, of the Covenant,

it was its duty to make with a view to effecting a settlement

of the dispute submitted for its consideration under

paragraph 9 of the said article, adopts, in virtue of

paragraph 4 of that article, the following report containing

a statement of the facts of the dispute and the recommendations

which are deemed just and proper in regard thereto.

PART I

Events at The Far East.

Adoption of The First Eight Chapters of The Report of

The Commission of Enquiry. Plan of The Report

The underlying causes of the dispute between China and Japan

are of considerable complexity. The Commission of Enquiry sent

by the Council to study the situation on the spot expresses

the view that the "issues involved in this conflict are not

as simple as they are often represented to be. They are,

on the contrary, exceedingly complicated, and only an intimate

knowledge of all the facts, as well as of their historical

background, should entitle anyone to express a definite opinion

upon them."

The first eight chapters of the report of the Commission of

Enquiry present a balanced, impartial and detailed statement

of the historical background of the dispute and of the main facts

in so for as they relate to events in Manchuria. It would be

both impracticable and superfluous either to summarise or

to recapitulate the report of the Commission of Enquiry,

which has been published separately; after examining

the observations communicated by the Chinese and Japanese

Governments, the Assembly adopts as ・・・・・

The Lytton Report on the Manchurian Crisis

The report of the Commission of Enquiry appointed

by the Council of the League of Nations, upon the relations

between China and Japan affecting Manchuria, generally known

as the Lytton Report,' was officially circulated to the Council

and the members of the League on October 1, 1932, having been

signed at Peiping early in September.

The appointment of the commission followed proceedings initiated

by the Chinese Government before the League under Article XI of

the Covenant which declares that "any war or threat of war,

whether immediately affecting any of the members of the League

or not "is" a matter of concern to the whole League."

It is significant that the action of the Council was initiated

under this article rather than under the more forceful provision

of Article X which speaks of "external aggression" and "territorial

integrity"; or under the categorical provisions of Article XII

dealing with "any dispute likely to lead to a rupture" and

providing for a submimion to arbitration or inquiry by the Council.

Article XI is more comprehensive in scope and allows greater

latitude in method.

The appeal by the Chinese Government to the Council requested it

to "take immediate steps to prevent the further development of

a situation endangering the peace of nations"

Two resolutions adopted by the Council on September 30 and

December 10,1931, respectively, were directed toward the taking

of such interim measures as were deemed essential to prevent

any aggravation of the situation growing out of the events

at Mukden on September 18-19,1931.

The resolution of December 10 went beyond the scope of

the earlier one, in that it expressed the desire of the Council

"to contribute towards a final and fundamental solution

by the two governments of the questions at issue between them."

The Council accordingly decided to appoint a commission of

five members "to study on the spot and to report to the Council

on any circumstances which, affecting international relations,

threaten to disturb the peace between China and Japan,

or the good understanding between them upon which peace depends."

It is important to note that both contending governments had

already proposed a neutral commission of enquiry to be sent

to the same of the dispute.

The commission of enquiry authorised by the Council was

to be purely advisory in character. It differed thus from

the commissions envisaged under the treaties of the First and

Second Hague Peace Conferences ・・・・・

068

Death on the Silkroad

by Richard Hering & Stuart Tanner

This extraordinary undercover report from China

exposes the suffering of thousands of Chinese

whose lives have been destroyed by nuclear testing.

It presents exclusive evidence from inside China of

spiraling levels of cancer and birth deformities

among the population of Xinjiang province -

part of the Great Silk Road -

which was opened to tourists in 1985.

Up until 1996, China had carried out extensive

nuclear tests in the Zinjiang province,

which is in the northwest corner of China,

bordering Kazakhstan. But Xinjiang is not unpopulated

and isolated, as was Bikini Atoll.

The filmmakers interviewed both victims and the doctors

who are struggling to cope with their medical problems

in the region's hospitals.

The documentary reveals that the tests were carried out

under highly dangerous conditions, which could have

consequences beyond China's borders.

The End

069

Ends and Means of

an Accounting System

from Introduction to Management Accounting

by Charles T. Horngren

An accounting system is a formal means of gathering data

to aid and coordinate collective decisions in light of

the overall goals or objectives of an organization.

The accounting system is the major quantitative information

system in almost every organization. An effective accounting

system provides information for three broad purposes or ends:

(1)

internal reporting to managers, for use in planning and

controlling routine operations;

(2)

internal reporting to managers, for use in strategic planning,

that is, the making of special decisions and the formulating

of overall policies and long-range plans;

(3)

external reporting to stockholders, government, and other

outside parties.

Both management (internal parties) and external parties share

an interest in all three important purposes, but the emphases

of financial accounting and of management (internal) accounting

differ.

Financial accounting has been mainly concerned with the third

purpose and has traditionally been oriented toward the historical,

stewardship aspects of external reporting.

The distinguishing feature of management accounting is its

emphasis on the planning and control purposes. Management accounting

is concerned with the accumulation, classification, and interpretation

of information that assists individual executives to fulfill

organizational objectives as revealed explicitly or implicitly

by top management.

What means do accounting systems use to fulfill the ends ?

Accounting data can be classified and reclassified in countless ways.

A helpful overall classification was proposed in a research study

of seven large companies with geographically dispersed operations:

The research team found that three types of information,

each serving as different means, often at various management levels,

raise and help to answer three basic questions:

1. Scorecard questions:

Am I doing well or badly?

2. Attention-directing questions:

Which problems should I look into?

3. Problem-solving questions:

Of the several ways of doing the job, which is the best ?

The scorecard and attention-directing uses of data are closely

related. The same data may serve a scorecard function for a foreman

and an attention-directing function for the foreman's superior.

For example, many accounting systems provide performance reports

in which actual results are compared with previously determined

budgets or standards. Such a performance report often helps

to answer scorecard questions and attention-directing questions

simultaneously. Furthermore, the actual results collected serve

not only control purposes but also the traditional needs of

financial accounting, which is chiefly concerned with the answering

of scorecard questions. This collection, classification, and

reporting of data is the task that dominates day-to-day accounting.

Problem-solving data may be used in long-range planning and

in making special, nonrecurring decisions, such as whether to make

or buy parts, replace equipment, or add or drop a product.

These decisions often require expert advice from specialists

such as industrial engineers, budgetary accountants, and

statisticians.

In sum, the accountants task of supplying information has

three facets:

1. Scorekeeping.

The accumulation of data. This aspect of accounting enables

both internal and external parties to evaluate organizational

performance and position.

2. Attention directing.

The reporting and interpreting of information that helps managers

to focus on operating problems, imperfections, inefficiencies,

and opportunities. This aspect of accounting helps managers

to concern themselves with important aspects of operations

promptly enough for effective action either through perceptive

planning or through astute day-to-day supervision. Attention

directing is commonly associated with current planning and control

and with the analysis and investigation of recurring routine

internal-accounting reports.

3. Problem solving.

This aspect of accounting involves the concise quantification

of the relative merits of possible courses of action, often

with recommendations as to the best procedure. Problem solving

is commonly associated with nonrecurring decisions, situations

that require special accounting analyses of reports.

The End

070

Business Realities

from Managing for Results Page 3~14

by Peter F. Drucker

That executives give neither sufficient time nor sufficient thought

to the future is a universal complaint.

Every executive voices it when he talks about his own working day

and when he talks or writes to his associates. It is a recurrent theme

in the articles and in the books on management.

It is a valid complaint. Executives should spend more time and thought

on the future of their business. They also should spend more time and thought

on a good many other things, their social and community responsibilities

for instance.

Both they and their businesses pay a stiff penalty for these neglects.

And yet, to complain that executives spend so little time on the work of

tomorrow is futile.

The neglect of the future is only a symptom;

the executive slights tomorrow because he cannot get ahead of today.

That too is a symptom. The real disease is the absence of any foundation

of knowledge and system for tackling the economic tasks in business.

Today's job takes all the executive's time, as a rule;

yet it is seldom done well. Few managers are greatly impressed

with their own performance in the immediate tasks.

They feel themselves caught in a "rat race," and managed

by whatever the mailboy dumps into their "in" tray.

They know that crash programs which attempt to "solve" this

or that particular "urgent" problem rarely achieve right and lasting results.

And yet, they rush from one crash program to the next.

Worse still, they known that the same problems recur again and again,

no matter how many times they are "solved."

Before an executive can think of tackling the future,

he must be able therefore to dispose of the challenges of today in less time

and with greater impact and permanence.

For this he needs a systematic approach to today's job.

There are three different dimensions to the economic task:

①

The present business must be made effective;

②

its potential must be identified and realized;

③

it must be made into a different business for a different future.

Each task requires a distinct approach. Each asks different questions.

Each comes out with different conclusions. Yet they are inseparable.

All three have to be done at the same time: today.

All three have to be carried out with the same organization,

the same resources of men, knowledge, and money, and

in the same entrepreneurial process.

The future is not going to be made tomorrow;

it is being made today, and largely by the decisions and

actions taken with respect to the tasks of today.

Conversely, what is being done to bring about the future directly

affects the present. The tasks overlap. They require one unified strategy.

Otherwise, they cannot really get done at all.

To tackle any one of these jobs, let alone all three together,

requires an understanding of the true realities of the business

as an economic system, of its capacity for economic performance,

and of the relationship between available resources and possible results.

Otherwise, there is no alternative to the "rat race."

This understanding never comes ready-made;

it has to be developed separately for each business.

Yet the assumptions and expectations that underlie it are largely common.

Businesses are different, but business is much the same,

regardless of size and structure, of products, technology and markets,

of culture and managerial competence.

There is a common business reality.

There are actually two sets of generalizations that apply

to most businesses most of the time: one with respect to the results

and resources of a business, one with respect to its efforts.

Together they lead to a number of conclusions regarding the nature

and direction of the entrepreneurial job.

Most of these assumptions will sound plausible, perhaps even familiar,

to most businessmen, but few businessmen ever pull them together

into a coherent whole.

Few draw action conclusions from them, no matter how much

each individual statement agrees with their experience and knowledge.

As a result, few executives base their actions on these,

their own assumptions and expectations.

1.

Neither results nor resources exist inside the business.

Both exist outside. There are no profit centers within the business;

there are only cost centers.

The only thing one can say with certainty about any business activity,

whether engineering or selling, manufacturing or accounting, is that

it consumes efforts and thereby incurs costs. Whether it contributes

to results remains to be seen.

Results depend not on anybody within the business nor on anything

within the control of the business. They depend on somebody outside--

the customer in a market economy, the political authorities

in a controlled economy.

It is always somebody outside who decides whether the efforts of

a business become economic results or whether they become

so much waste and scrap.

The same is true of the one and only distinct resource of any business:

knowledge.

Other resources, money or physical equipment, for instance,

do not confer any distinction.

What does make a business distinct and

what is its peculiar resource is its ability to use knowledge of all kinds

--from scientific and technical knowledge to social, economic, and

managerial knowledge.

It is only in respect to knowledge that a business can be distinct,

can therefore produce something that has a value in the market place.

Yet knowledge is not a business resource. It is a universal social resource.

It cannot be kept a secret for any length of time.

"What one man has done, another man can always do again" is old and

profound wisdom. The one decisive resource of business, therefore,

is as much outside of the business as are business results.

Indeed, business can be defined as a process that converts

an outside resource, namely knowledge, into outside results,

namely economic values.

2.

Results are obtained by exploiting opportunities,

not by solving problems.

All one can hope to get by solving a problem is to restore normality.

All one can hope, at best, is to eliminate a restriction on the capacity

of the business to obtain results.

The results themselves must come

from the exploitation of opportunities.

3.

Resources, to produce results, must be allocated to opportunities

rather than to problems. Needless to say, one cannot shrug off all problems,

but they can and should be minimized.

Economists talk a great deal about the maximization of profit in business.

This, as countless critics have pointed out, is so vague a concept as

to be meaningless.

But "maximization of opportunities" is a meaningful, indeed a precise,

definition of the entrepreneurial job. It implies that effectiveness rather than

efficiency is essential in business. The pertinent question is not how to do things right

but how to find the right things to do,

and to concentrate resources and efforts on them.

4.

Economic results are earned only by leadership,

not by mere competence.

Profits are the rewards for making a unique, or at least a distinct,

contribution in a meaningful area;

and what is meaningful is decided by market and customer.

Profit can only be earned by providing something the market accepts

as value and is willing to pay for as such.

And value always implies the differentiation of leadership.

The genuine monopoly, which is as mythical a beast as the unicorn

(save for politically enforced, that is, governmental monopolies),

is the one exception.

This does not mean that a business has to be the giant of its

industry nor that it has to be first in every single product line,

market, or technology in which it is engaged.

To be big is not identical with leadership. In many industries

the largest company is by no means the most profitable one,

since it has to carry product lines, supply markets, or apply

technologies where it cannot do a distinct, let alone a unique job.

The second spot, or, even the third spot is often preferable,

for it may make possible that concentration on one segment of

the market, on one class of customer, on one application of

the technology, in which genuine leadership often lies.

In fact, the belief of so many companies that they could or

should have leadership in everything within their market or industry

is a major obstacle to achieving it.

But a company which wants economic results has to have leadership

in something of real value to a customer or market.

.

It may be in one narrow but important aspect of the product line,

it may be in its service, it may be in its distribution, or it may be in its ability

to convert ideas into salable products on the market speedily and at low cost.

Unless it has such leadership position, a business, a product, a service,

becomes marginal.

It may seem to be a leader,

may supply a large share of the market,

may have the full weight of momentum, history, and tradition behind it.

But the marginal is incapable of survival in the long run,

let alone of producing profits. It lives on borrowed time.

It exists on sufferance and through the inertia of others.

Sooner or later, whenever boom conditions abate,

it will be squeezed out.

The leadership requirement has serious implications

for business strategy. It makes most questionable, for instance,

the common practice of trying to catch up with a competitor

who has brought out a new or improved product.

All one can hope to achieve thereby is to become a little less marginal.

It also makes questionable "defensive research" which throws scarce

and expensive resources of knowledge into the usually futile task of

slowing down the decline of a product that is already obsolete.

5.

Any leadership position is transitory and likely to be shortlived.

No business is ever secure in its leadership position.

The market in which the results exist, and the knowledge

which is the resource, are both generally accessible.

No leadership position is more than a temporary advantage.

In business (as in a physical system) energy always tends toward diffusion.

Business tends to drift from leadership to mediocrity.

And the mediocre is threequarters down the road to being marginal.

Results always drift from earning a profit toward earning, at best,

a fee which is all competence is worth.

It is, then, the executive's job to reverse the normal drift.

It is his job to focus the business on opportunity and away from problems,

to re-create leadership and counteract the trend toward mediocrity,

to replace inertia and its momentum by new energy and new direction.

The second set of assumptions deals with the efforts

within the business and their cost.

6.

What exists is getting old. To say that most executives spend most

of their time tackling the problems of today is euphemism.

They spend most of their time on the problems of yesterday.

Executives spend more of their time trying to unmake the past than

on anything else.

This, to a large extent, is inevitable. What exists today is of necessity

the product of yesterday. The business itself-its present resources,

its efforts and their allocation, its organization as well as its products,

its markets and its customers-xpresses necessarily decisions and actions

taken in the past.

Its people, in the great majority, grew up in the business of yesterday.

Their attitudes, expectations, and values were formed at an earlier time;

and they tend to apply the lessons of the past to the present.

Indeed, every business regards what happened in the past as normal,

with a strong inclination to reject as abnormal whatever does not fit

the pattern.

No matter how wise, forward-looking, or courageous the decisions

and actions were when first made, they will have been overtaken

by events by the time they become normal behavior and the routine

of a business.

No matter how appropriate the attitudes were when formed,

by the time their holders have moved into senior,

policy making positions, the world that made them no longer exists.

Events never happen as anticipated; the future is always different.

Just as generals tend to prepare for the last war, businessmen always

tend to react in terms of the last boom or of the last depression.

What exists is therefore always aging. Any human decision or

action starts to get old the moment it has been made.

It is always futile to restore normality; "normality" is only the reality

of yesterday. The job is not to impose yesterday's normal

on a changed today; but to change the business, its behavior,

its attitudes, its expectations -- as well as its products, its markets,

and its distributive channels -- fit the new realities.

7.

What exists is likely to be misallocated. Business enterprise is not

a phenomenon of nature but one of society. In a social situation,

however, events are not distributed according to the "normal distribution"

of a natural universe (that is, they are not distributed according to

the bell-shaped Gaussian curve).

In a social situation a very small number of events at one extreme --

the first 10 per cent to 20 per cent at most-- acount for 90 per cent

of all results; whereas the great majority of events accounts for 10 per cent

or so of the results.

This is true in the market place: a handful of large customers out of

many thousands produce the bulk of orders; a handful of products

out of hundreds of items in the line produce the bulk of the volume;

and so on.

It is true of sales efforts: a few salesmen out of several hundred

always produce two-thirds of all new business.

It is true in the plant: a handful of production runs account for

most of the tonnage.

It is true of research: the same few men in the laboratory are apt

to produce nearly all the important innovations.

It also holds true for practically all personnel problems:

the bulk of the grievances always comes from a few places

or from one group of employees (for example, from the older

unmarried women or from the clean-up men on the night shift),

as does the great bulk of absenteeism, of turnover, of suggestions

under a suggestion system, of accidents. As studies at the New York

Telephone Company have shown, this is true even in respect to sickness.

The implications of this simple statement about normal distribution

are broad.

It means, first: while 90 per cent of the results are being produced

by the first 10 per cent of events, 90 per cent of the costs are incurred

by the remaining and resultless 90 per cent of events.

In other words, results and costs stand in inverse relationship

to each other. Economic results are, by and large, directly

proportionate to revenue, while costs are directly proportionate

to the number of transactions. (The only exceptions are the

purchased materials and parts that go directly into the final product.)

A second implication is that resources and efforts will normally

allocate themselves to the 90 per cent of events that produce

practically no results. They will allocate themselves to the number of

events rather than to the results.

In fact, the most expensive and potentially most productive resources

(i.e., highly trained people) will misallocate themselves the worst.

For the pressure exerted by the bulk of transactions is fortified

by the individual's pride in doing the difficult--whether productive or not.

This has been proved by every study. Let me give some examples:

A large engineering company prided itself on the high quality and

reputation of its technical service group, which contained several

hundred expensive men. The men were indeed first-rate.

But analysis of their allocation showed clearly that while they worked hard,

they contributed little.

Most of them worked on the "interesting" problems--especially those

of the very small customers--problems which, even if solved,

produced little business.

The automobile industry was the company's major customer and

accounted for almost one-third of all purchases. But few technical

service people had within memory set foot in the engineering department

or the plant of an automobile company.

"General Motors and Ford don't need me; they have their own people"

was their reaction.

Similarly, in many companies, salesmen are misallocated.

The largest group of salesmen (and the most effective ones)

are usually put on the products that are hard to sell,

either because they are yesterday's products or because they are

alsorans which managerial vanity desperately is trying to make into winners.

Tomorrow's important products rarely get the sales effort required.

And the product that has sensational success in the market,

and which therefore ought to be pushed all out, tends to be slighted.

"It is doing all right without extra effort, after all" is the common conclusion.

Research departments, design staffs, market development efforts,

even advertising efforts have been shown to be allocated the same way

in many companies--by transactions rather than by results,

by what is difficult rather than by what is productive,

by yesterday's problems rather than by today's and tomorrow's opportunities.

A third and important implication is that revenue money and

cost money are rarely the same money stream.

Most businessmen see in their mind's eye -- and most accounting

presentations assume -- that the revenue stream feeds back

into the cost stream, which then, in turn, feeds back into the revenue stream.

But the loop is not a closed one. Revenue obviously produces the wherewithal

for the costs. But unless management constantly works at directing efforts

into revenue-producing activities, the costs will tend to allocate themselves

by drifting into nothing-producing activities, into sheer busy-ness.

In respect then to efforts and costs as well as to resources and

results the business tends to drift toward diffusion of energy.

There is thus need for constant reappraisal and redirection; and

the need is greatest where it is least expected: in making the present

business effective.

It is the present in which a business first has to perform with effectiveness.

It is the present where both the keenest analysis and the greatest energy

are required.

Yet it is dangerously tempting to keep on patching yesterday's garment

rather than work on designing tomorrow's pattern.

A piecemeal approach will not suffice. To have a real understanding

of the business, the executive must be able to see it in its entirety.

He must be able to see its resources and efforts as a whole and

to see their allocation to products and services, to markets, customers,

end-uses, to distributive channels.

He must be able to see which efforts go onto problems and

which onto opportunities.

He must be able to weigh alternatives of direction and allocation.

Partial analysis is likely to misinform and misdirect.

Only the over-all view of the entire business as an economic system

can give real knowledge.

8.

Concentration is the key to economic results. Economic results require

that managers concentrate their efforts on the smallest number of products,

product lines, services, customers, markets, distributive channels, end-uses,

and so on, that will produce the largest amount of revenue.

Managers must minimize the amount of attention devoted to products

which produce primarily costs because, for instance, their volume is too small

or too splintered.

Economic results require that staff efforts be concentrated on the few activities

that are capable of producing significant business results.

Effective cost control requires a similar concentration of work and efforts

on those few areas where improvement in cost performance will have significant

impact on business performance and results--that is, on those areas where

a relatively minor increase in efficiency will produce a major increase

in economic effectiveness.

Finally, human resources must be concentrated on a few major opportunities.

This is particularly true for the high-grade human resources through which

knowledge becomes effective in work. And, above all it is true for the scarcest,

most expensive, but also potentially most effective of all human resources

in a business: managerial talent.

No other principle of effectiveness is violated as constantly today

as the basic principle of concentration. This, of course, is true

not only of businesses. Governments try to do a little of everything.

Today's big university (especially in the United States) tries to be all things

to all men, combining teaching and research, community services,

consulting activities, and so on. But business --especially large business--

is no less diffuse.

Only a few years ago it was fashionable to attack American industry

for "planned obsolescence." And it has long been a favorite criticism of

industry, especially American industry, that it imposes "deadening

standardization." Unfortunately industry is being attacked for doing

what it should be doing and fails to do.

Large United States corporations pride themselves on being willing

and able to supply any specialty, to satisfy any demand for variety,

even to stimulate such demands. Any number of businesses boast

that they never of their own free will abandon a product.

As a result, most large companies end up with thousands of items

in their product line-- and all too frequently fewer than twenty really sell.

However, these twenty or fewer items have to contribute revenues

to carry the costs of the 9,999 non-sellers.

Indeed, the basic problem of United States competitive strength

in the world today may be product clutter. If properly costed,

the main lines in most of our industries prove to be fully competitive,

despite our high wage rate and our high tax burden.

But we fritter away our competitive advantage in the volume products

by subsidizing an enormous array of specialties, of which only a few recover

their true cost.

In electronics, for instance, the competition of the Japanese portable

transistor radio rests on little more than the Japanese concentration

on a few models in this one line--is against the uncontrolled plethora of

barely differentiated models in the United States manufacturers' lines.

We are similarly profligate in this country with respect to staff activities.

Our motto seems to be: "Let's do a little bit of everything"

- personnel research, advanced engineering, customer analysis,

international economics, operations research, public relations, and so on.

As a result, we build enormous staffs, and yet do not concentrate

enough effort in any one area.

Similarly, in our attempts to control costs, we scatter our efforts

rather than concentrate them where the costs are.

Typically the cost-reduction program aims at cutting a little bit -

say, 5 or 10 per cent - off everything. This across-the-board cut is

at best ineffectual; at worst, it is apt to cripple the important,

result-producing efforts which usually get less money than they need

to begin with.

But efforts that are sheer waste are barely touched by the typical

cost-reduction program; for typically they start out with a generous budget.

These are the business realities, the assumptions that are likely

to be found valid by most businesses at most times, the concepts

with which the approach to the entrepreneurial task has to begin.

They have only been sketched here in outline; each will be discussed

in detail in the course of the book. That these are only assumptions

should be stressed. They must be tested by actual analysis;

and one or the other assumption may well be found not to apply

to any one particular business at any one particular time.

Yet they have sufficient probability to provide the foundation

for the analysis the executive needs to understand his business.

They are the starting points for the analysis needed for all three

of the entrepreneurial tasks: making effective the present business;

finding business potential; and making the future of the business.

The small and apparently simple business needs this understanding

just as much as does the big and highly complex company.

Understanding is needed as much for the immediate task of effectiveness

today as it is for work on the future, many years hence. It is a necessary tool

for any executive who takes seriously his entrepreneurial responsibility.

And it is a tool which can neither be fashioned for him nor wielded for him.

He must take part in making it and using it. The ability to design and develop

this tool and the competence to use it should be standard equipment

for the business executive.

The End

関連サイト:予習挑戦型へ脱皮して潜在能力を開発する

Materials to Create an English Brain by the Copy-Writing Method

5.毎日コピー英作文法実践で英語脳を創る⑤

6.毎日コピー英作文法実践で英語脳を創る⑥

8.毎日コピー英作文法実践で英語脳を創る⑧