中国の核心的利益追求

−暴力団・中国の悪辣なナワバリ拡大挑発行為エスカレート

2013年11月

関連サイト:領土問題についての意見

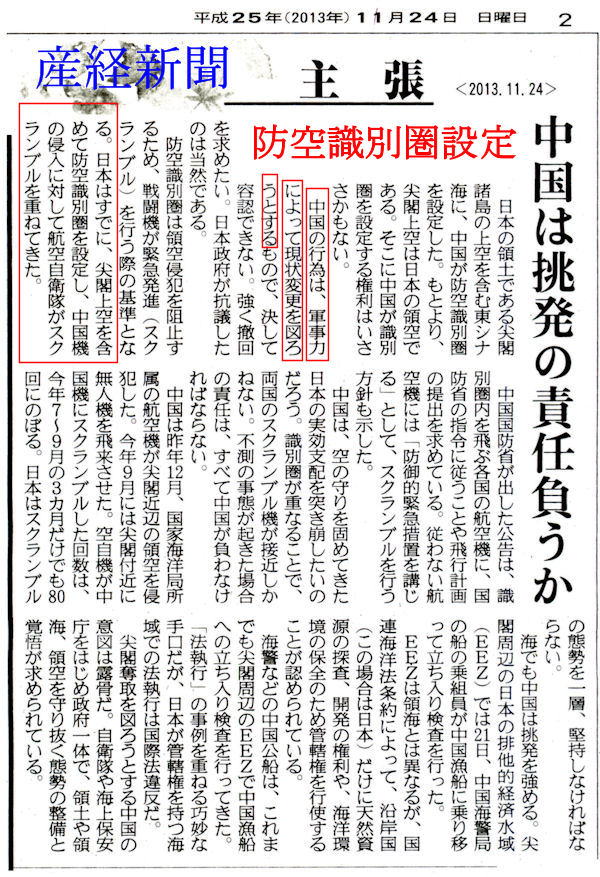

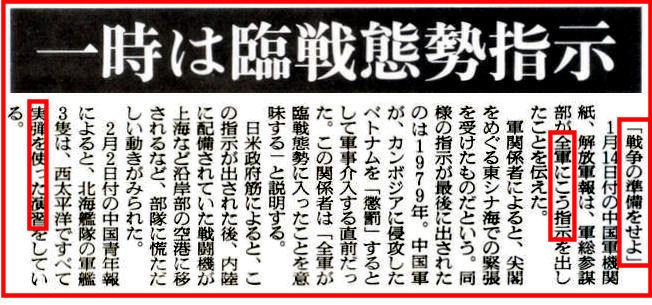

中国の防空識別圏設定

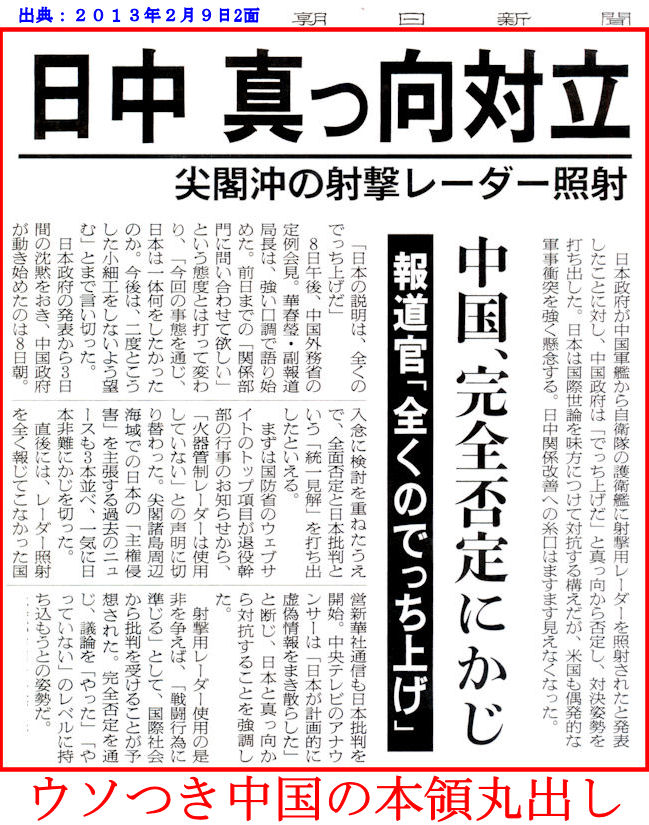

ウソをついて、責任転嫁することは、暴力団・中国では常識だ!

これからも、悪質なウソをついて、中国国民と国際社会を、

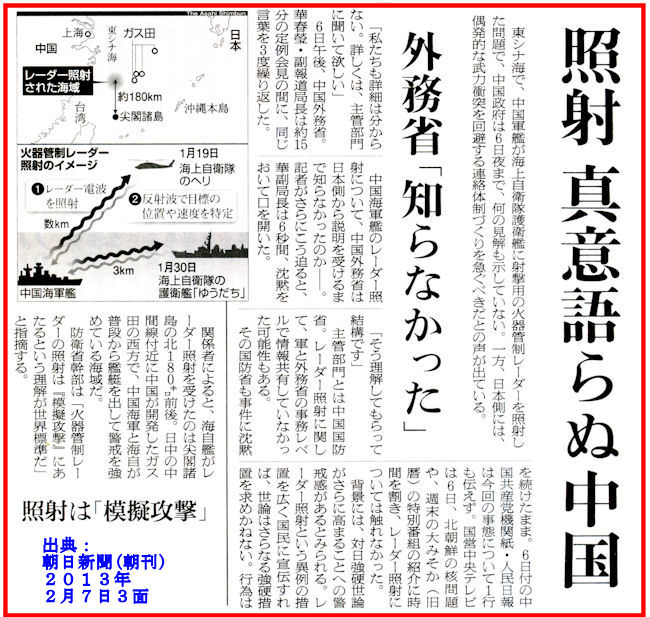

徹底的にダマスぞ!!

韓国と連携して、「現在も日本は悪者」と、喚きたてるぞ!!!

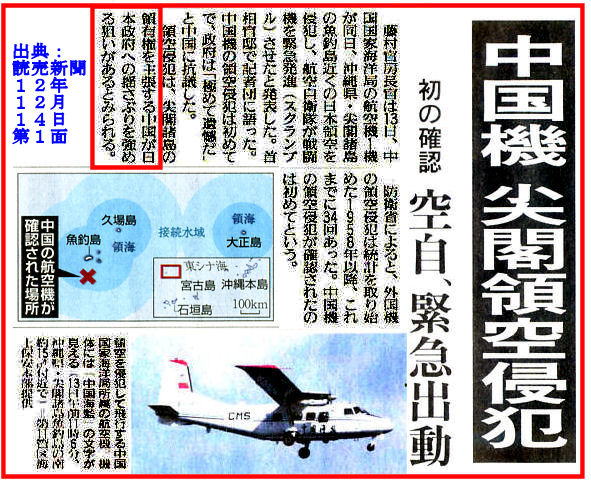

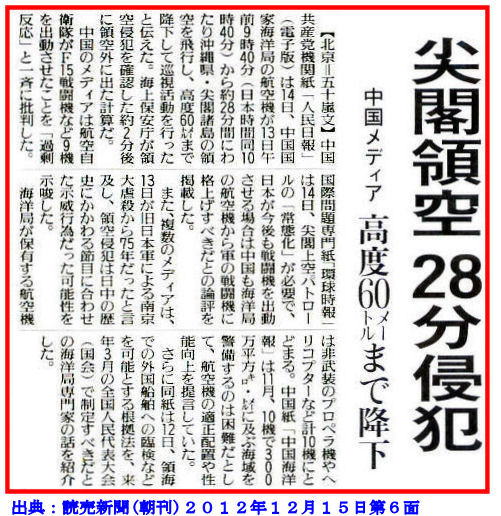

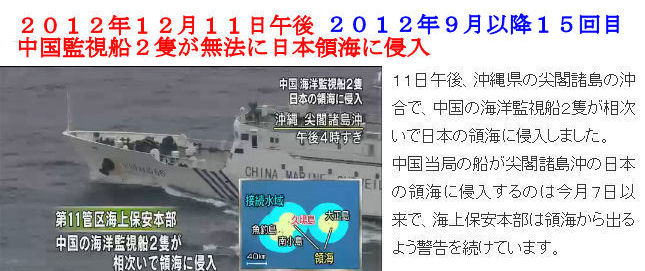

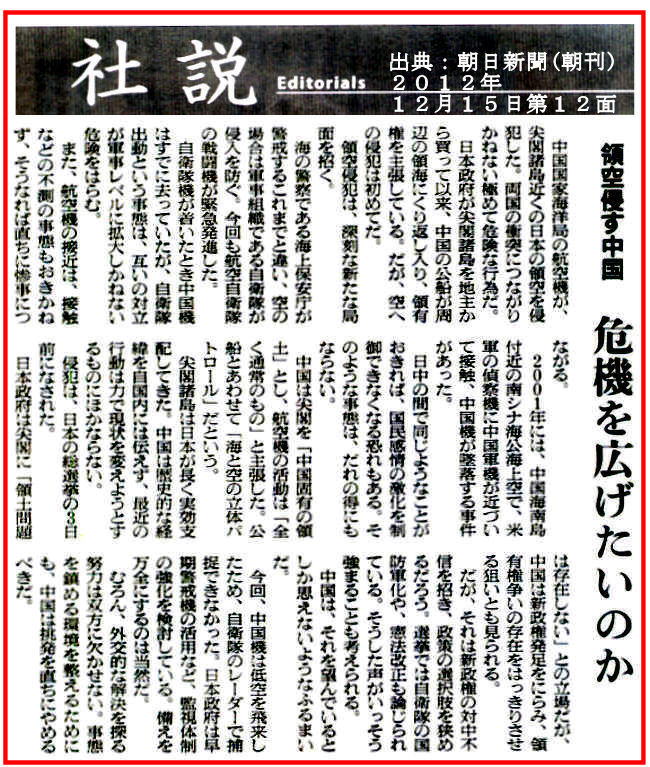

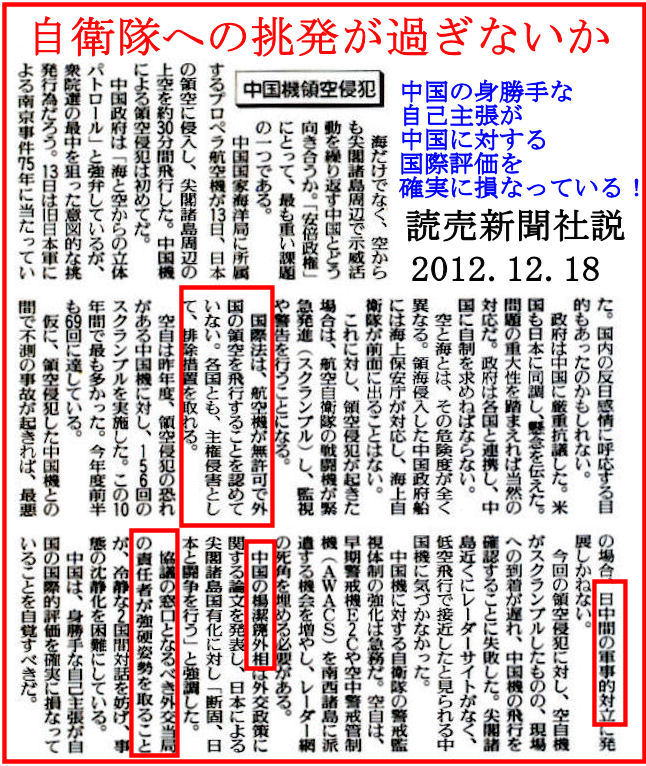

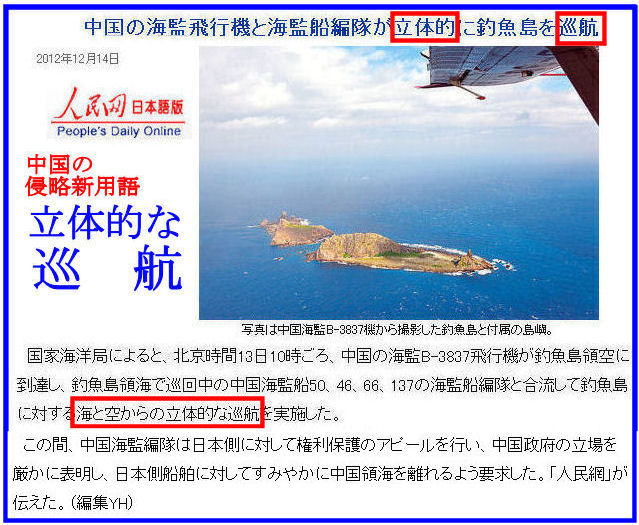

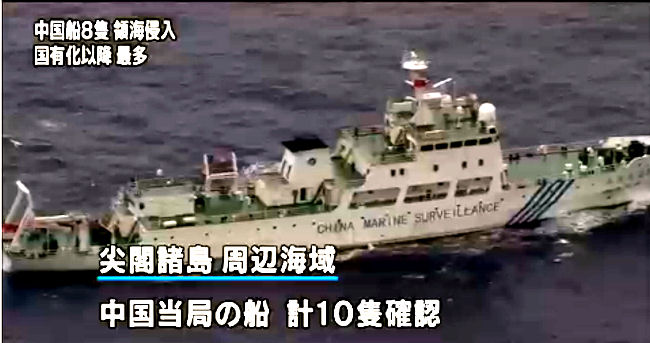

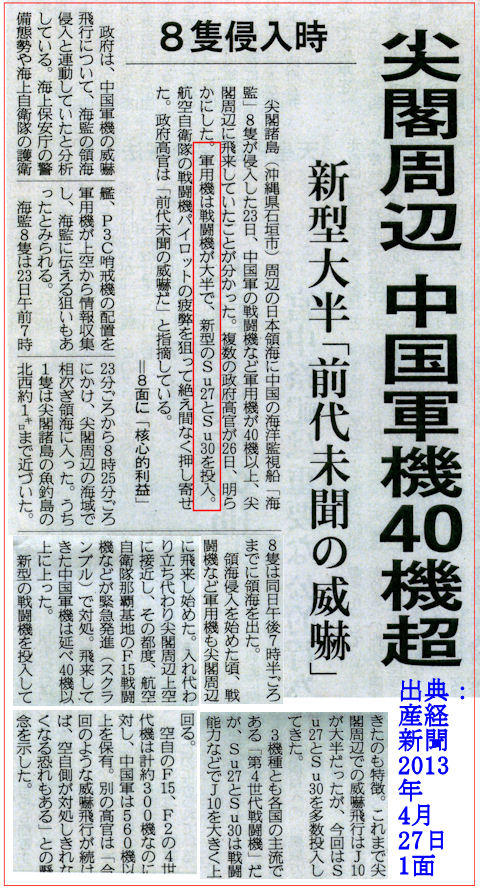

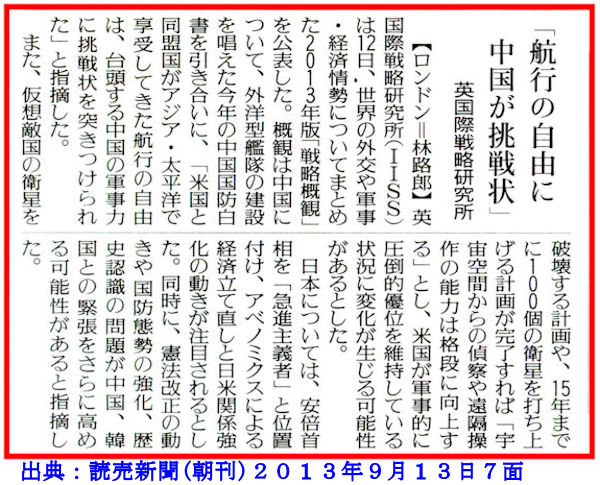

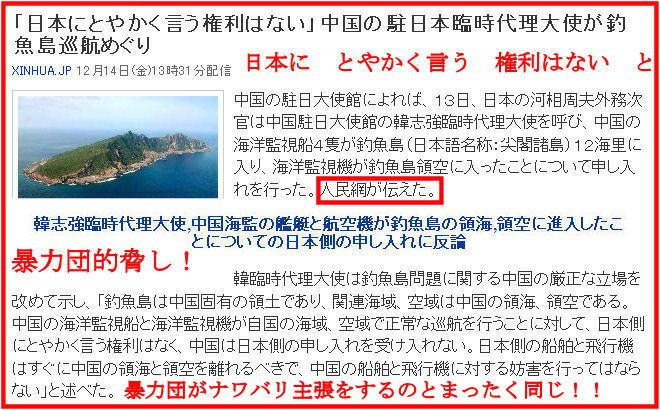

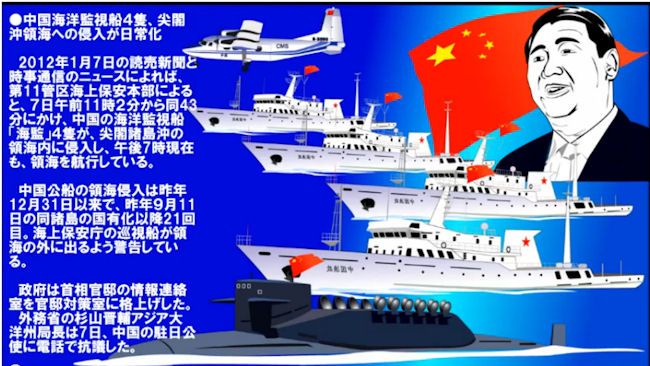

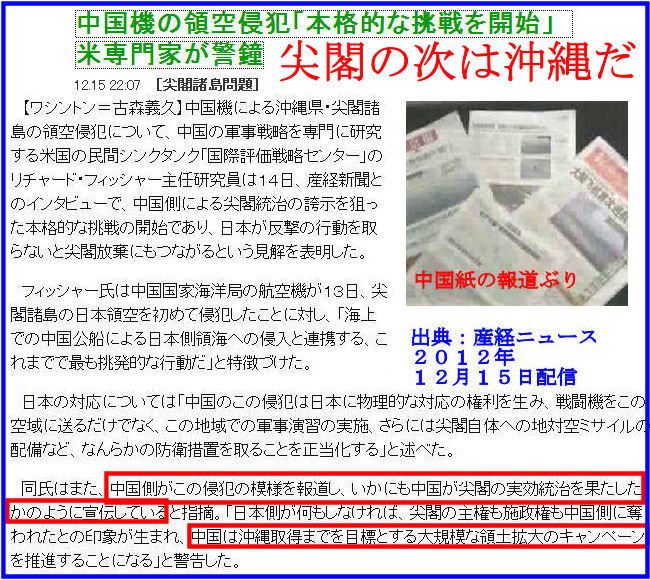

「立体的な巡航で、核心的利益を護る」との暴力団・中国のナワバリ拡大主張

中国メディアの報道−−日本を挑発して、国際平和を脅かしたい! くわばら、くわばら!!

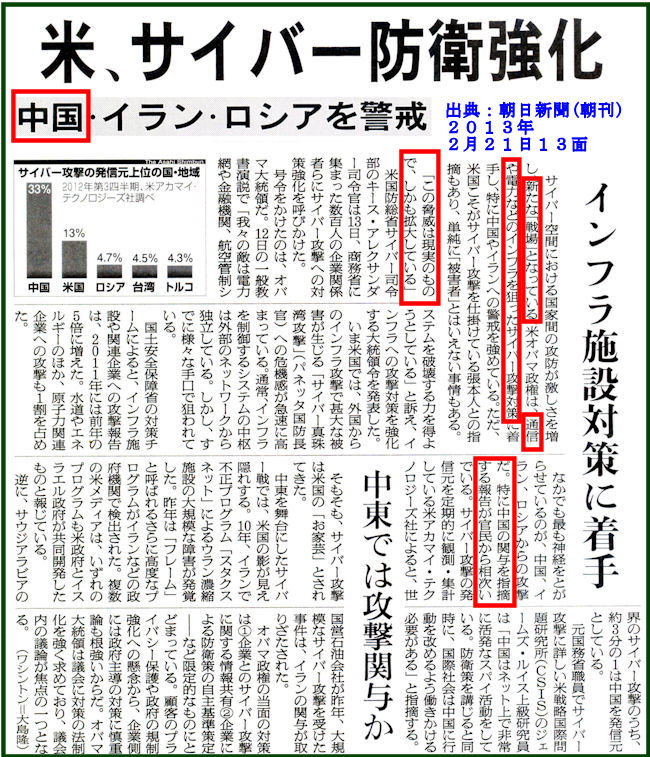

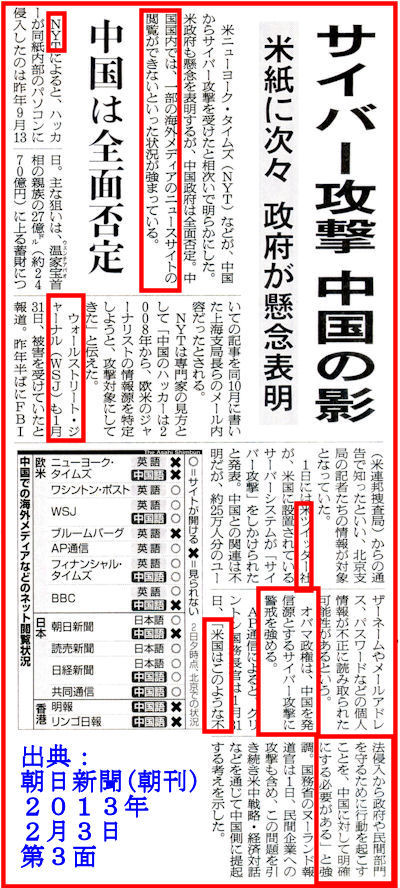

中国、国家ぐるみでサイバー攻撃

攻撃元は中国人民解放軍

標的は米国ビジネス

オバマ政権 強い危機感

2013年2月21日各紙報道

米国の情報セキュリティ−会社マンディアント社が2013年2月

19日に発表した報告書は、中国人民解放軍のサイバー攻撃への

関与を浮き彫りにした。

米国では中国の対米サイバー攻撃が、米国社会に深刻な打撃を

与えることへの懸念が高まっている。オバマ政権はこれまで

米中関係への悪影響を懸念し、深入りを避けてきたが、対策の強化を

迫られている。

米国の情報セキュリティー会社マンディアント社は2004年以来、

数百の企業及び諸団体のコンピューター・システムがサイバー攻撃

された事実について追跡調査した。その結果、サイバー攻撃の発信元が

上海・浦東新区に集中していることが判明した。サイバー攻撃の際の

IPアドレスを詳しく調べたところ、同区に拠点を置く、人民解放軍

総参謀部所属の「61398部隊」によるサイバー攻撃と判明した。

同報告書によると、上海からの一連のサイバー攻撃で2006年以降、

米国など英語圏を中心とする企業少なくとも141社がサイバー攻撃を

受けた。

設計図、特許品の製造工程、試験結果、営業計画、価格表、提携合意書

から、企業幹部の電子メール、連絡リストまで盗まれていた。

サイバー攻撃は複数の企業に同時に行われていた。平均で1年、中には

5年近く気づかないまま被害を受けていた企業もあった。

中国電信の内部資料には、61398部隊に光ファイバー通信設備を

提供したことを説明する文書があり、国有企業によってサイバー攻撃

環境が整えられていた。

2013年1月までの2年間で、832種類のIPアドレスがサイバー

攻撃に使われていたことも確認された。サイバー攻撃が、豊富な資金と

組織力によるものであることがが裏付けられた。

サイバー攻撃の規模から判断して、サイバー攻撃作戦は、数百人単位で

行われたとみられている。

この報告書に対し、カーニー米大統領報道官は、2013年2月19日の

記者会見で、「我々は、中国人民解放軍も含めた中国政府高官に、

サイバー攻撃問題についての米国の懸念を提起し続けている」と述べ、

対策を継続する考えを強調した。

ブッシュ政権下で中央情報局(CIA)長官を務めたマイケル・ヘイデン氏は

2013年2月19日、ワシントンで講演し、報告書の内容について

「いったい何が新しい話なのか」と述べ、米国の歴代政権で、中国政府や

中国人民解放軍のサイバー攻撃への関与が継続的に問題視されてきたこと

を明らかにした。ヘイデン氏は「国家が別の国家の機密を盗むのでなく、

米国のビジネスを攻撃している」と指摘し、民間企業だけで対応するのは、

もはや不可能との見方を示した。

ヘイデン氏はさらに、中国が「米国の重要な社会基盤を制御するネット

ワーク」を標的にしていると述べ、送電網などを遮断する攻撃が将来

行われることへの懸念を示した。

米紙ニューヨーク・タイムズによると、パイプラインや送電網の安全

システムを遠隔操作するソフトウエアの制作会社も中国からのサイバー

攻撃を受けた。マンディアント社は調査を行った企業名や業種を公表

していない。

オバマ大統領は2013年2月12日、サイバー攻撃に関する情報を

官民が共有し、民間企業が攻撃に対処する安全基準を採用することを促す

大統領令を出したばかり。

マンディアント社が、今回、中国側に手の内を知られ、攻撃方法を

変えられる危険を承知で報告書発表に踏み切った背景には、企業側の

危機意識を高めたいオバマ政権側の了解があったとみられる。

ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙によると、CIAなど16の米情報機関が

最近まとめた国家情報評価(NIE)は、「中国が最も激しく米国への

サイバー攻撃を図っている」と指摘している。中国のサイバー攻撃問題は

米中間の大きな火種となりそうだ。

米国、英国からの警告

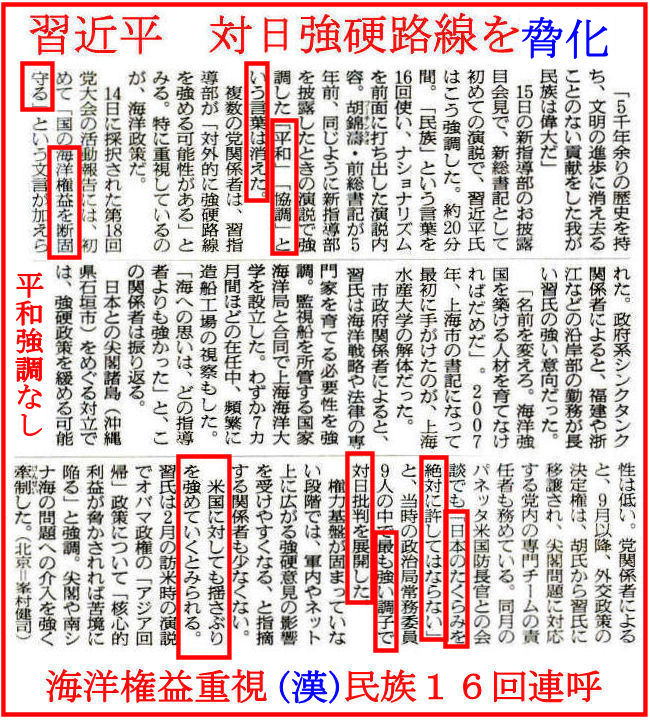

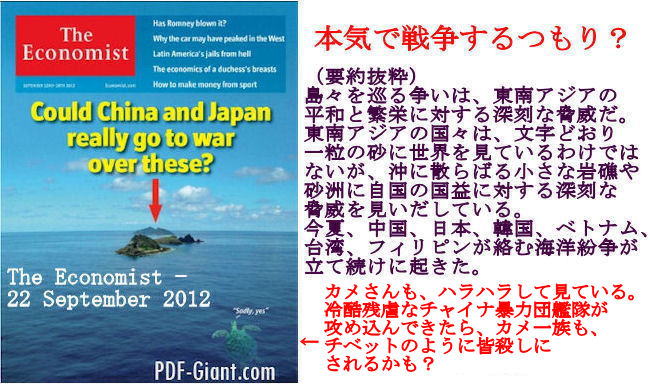

出典:The Economist - 22 September 2012

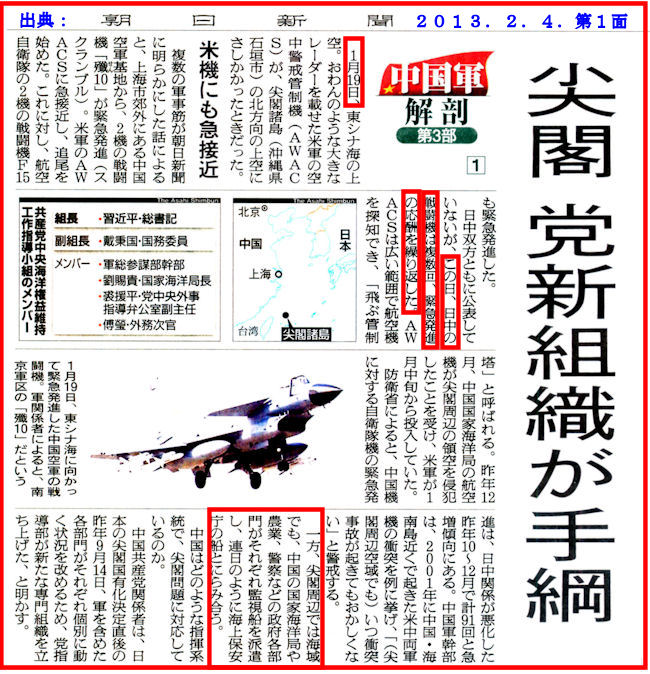

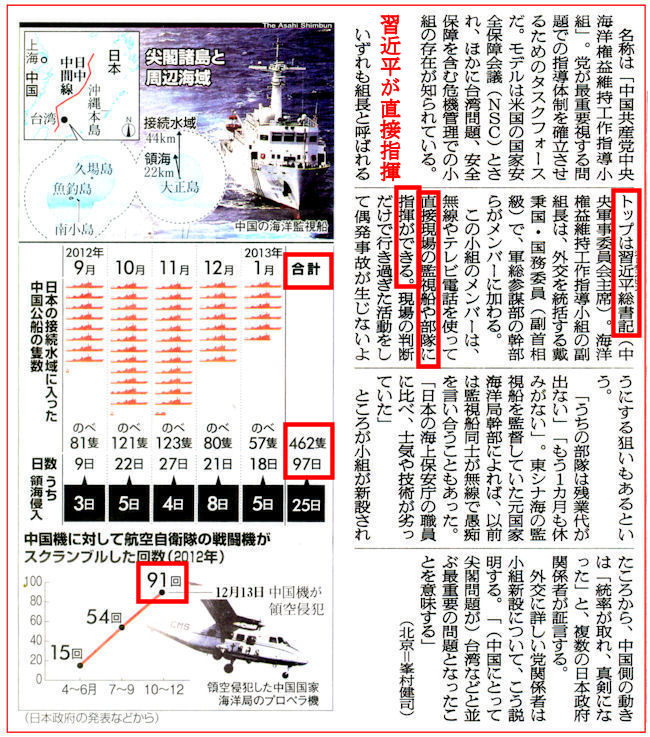

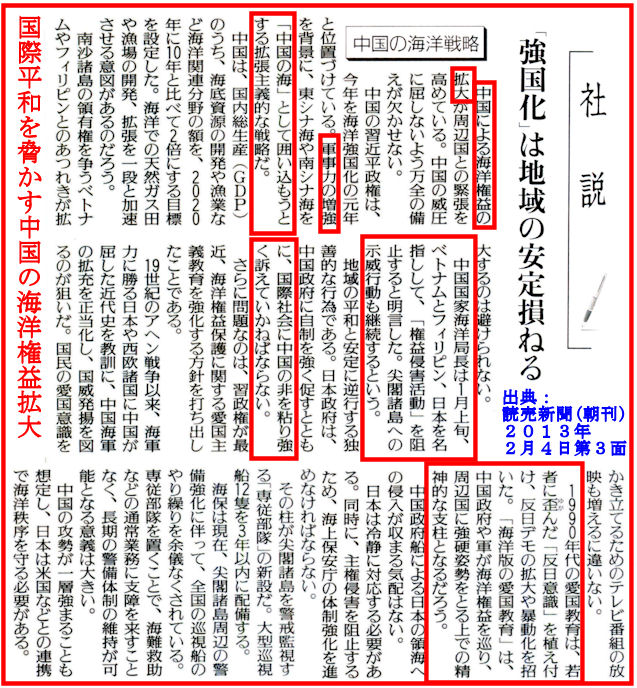

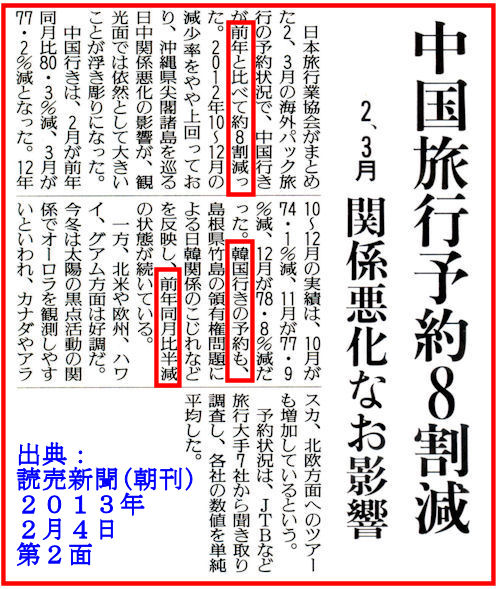

2013年2月4日報道

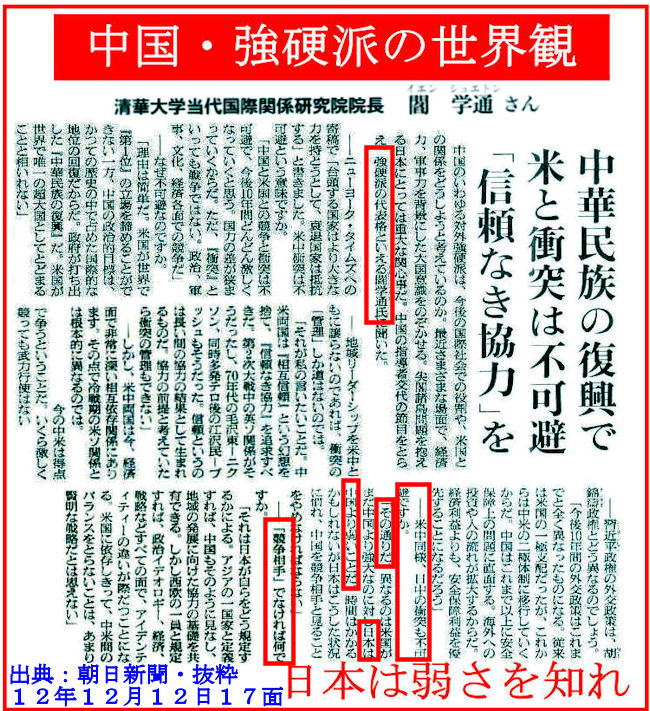

日本から、カネと技術は獲れるだけ獲った!

今度は、尖閣、沖縄を手始めに、島を獲るぞ!

国際平和? それは別の惑星の話では?(中国政府高官談?)

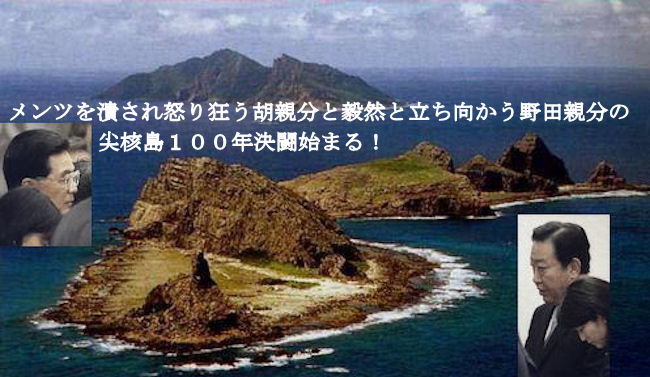

習親分と安倍親分に引き継がれた尖閣島100年決闘始まる?

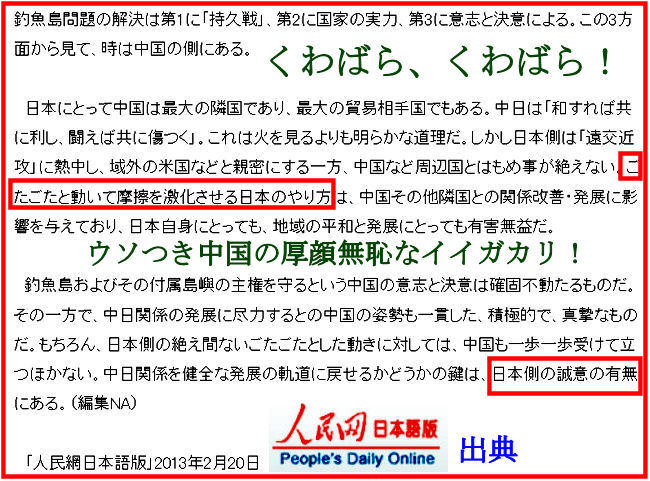

尖閣が波風もなく平穏であることは、今後、相当長期間ないだろう。

我々はこのことをはっきりと認識している。心の準備もできている。

複雑な情勢を前に、中国には不動の精神力と意志が十分にある。

面倒が大きいほど冷静になる。試練が大きいほど揺るぎなくなる。

核心的利益(21世紀版中国の帝国主義侵略戦争スローガン)の放棄を

(我利我利ガリガリ亡者の)中国に期待するのは、ナンセンスの極みだ。

出典:人民網Online 2012年8月6日配信

*人民網Onlineは中国共産党機関紙・人民日報のインターネット版

−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−

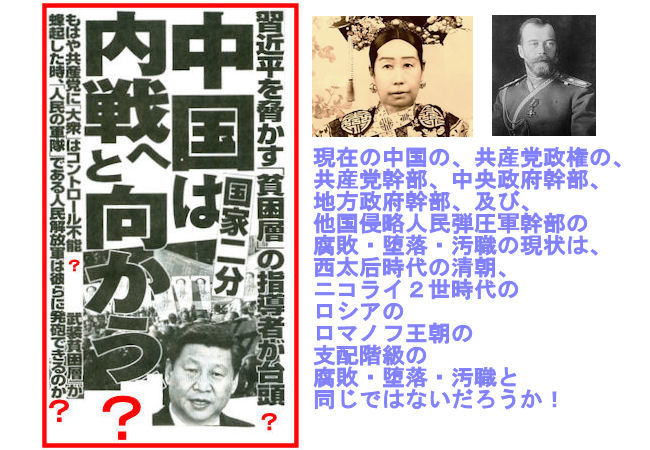

国際平和・感謝貢献の理念を欠き、愛国教育と称する対日憎悪感植え付けの

洗脳教育を幼稚園段階から行って、日本や周辺の国々を武力威嚇・侵略する

帝国主義国・非民主主義国家・中国に、明るい未来が有るのだろうか?

チベット族、ウイグル族、満州族等の非漢民族の人道に反する迫害・拷問・

殺害等の異民族絶滅政策を推し進める軍事大国・非民主主義国家・中国に、

明るい未来が有るのだろうか?

言論の自由がない中国では、支配者階級は

やりたい放題、何でもできますよ!共産党バンザイ!

中国には、相続税はないのです。

資産は、そっくりそのまま、子孫に残せるのです。

特権蓄財高官にとって中国はスバラシイ国です。

習近平閣下バンザイ! 温家宝閣下バンザイ!

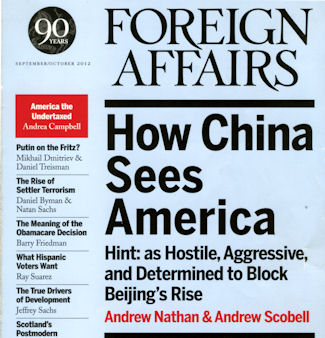

How China Sees America

-The Sum of Beijing's Fears

by Andrew Nathan & Andrew Scobell

from Foreign Affairs September/October 2012 issue

"GREAT POWER" is a vague term, but China deserves it by any measure:

the extent and strategic location of its territory,

the size and dynamism of its population,

the value and growth rate of its economy,

the massive size of its share of global trade,

and the strength of its military.

China has become one of a small number of countries that have significant

national interests in every part of the world and that command the attention,

whether willingly or grudgingly, of every other country and every international

organization.

And perhaps most important, China is the only country widely seen

as a possible threat to U.S. predominance.

Indeed, China's rise has led to fears that the country will soon overwhelm

its neighbors and one day supplant the United States as a global hegemon.

But widespread perceptions of China as an aggressive, expansionist power

are off base. Although China's relative power has grown significantly

in recent decades, the main tasks of Chinese foreign policy are defensive

and have not changed much since the Cold War era:

to blunt destabilizing influences from abroad,

to avoid territorial losses,

to reduce its neighbors' suspicions,

and to sustain economic growth.

What has changed in the past two decades is that

China is now so deeply integrated into the world economic system

that its internal and regional priorities have become part of a larger quest:

to define a global role that serves Chinese interests but also wins

acceptance from other powers.

Chief among those powers, of course, is the United States, and

managing the fraught U.S.-Chinese relationship is Beijing's foremost

foreign policy challenge. And just as Americans wonder whether

China's rise is good for U.S. interests or represents a looming threat,

Chinese policymakers puzzle over whether the United States intends

to use its power to help or hurt China.

Americans sometimes view the Chinese state as inscrutable.

But given the way that power is divided in the U.S. political system and

the frequent power turnovers between the two main parties in the United States,

the Chinese also have a hard time determining U.S. intentions.

Nevertheless, over recent decades, a long-term U.S. strategy seems

to have emerged out of a series of American actions toward China.

So it is not a hopeless exercise - indeed, it is necessary for the Chinese

to try to analyze the United States.

Most Americans would be surprised to learn the degree to which

the Chinese believe the United States is a revisionist power

that seeks to curtail China's political influence and harm China's interests.

This view is shaped not only by Beijing's understanding of Washington

but also by the broader Chinese view of the international system and

China's place in it, a view determined in large part by China's

acute sense of its own vulnerability.

THE FOUR RINGS

The World as seen from Beijing is a terrain of hazards, beginning

with the streets outside the policymaker's window,

to land borders and sea-lanes thousands of miles away,

to the mines and oil fields of distant continents.

These threats can be described in four concentric rings.

In the first ring,

the entire territory that China administers or claims,

Beijing believes that China's political stability and territorial integrity

are threatened by foreign actors and forces.

Compared with other large countries,

China must deal with an unparalleled number of outside actors

trying to influence its evolution,

often in ways the regime considers detrimental to its survival.

Foreign investors, development advisers, tourists,

and students swarm the country, all with their own ideas

about how China should change.

Foreign foundations and governments give financial and technical support

to Chinese groups promoting civil society.

Dissidents in Tibet and Xinjiang receive moral and diplomatic support

and sometimes material assistance from ethnic diasporas and

sympathetic governments abroad.

Along the coast, neighbors contest maritime territories that Beijing claims.

Taiwan is ruled by its own government, which enjoys diplomatic recognition

from 23 states and a security guarantee from the United States.

At China's borders, policymakers face

a second ring of security concerns,

involving China's relations with 14 adjacent countries.

No other country except Russia has as many contiguous neighbors.

They include five countries with which China has fought wars

in the past 70 years

(India, Japan, Russia, South Korea, and Vietnam)

and a number of states ruled by unstable regimes.

None of China's neighbors perceives its core national interests

as congruent with Beijing's.

But China seldom has the luxury of dealing with any of its neighbors

ih a purely bilateral context.

The third ring of Chinese security concerns

consists of the politics of the six distinct geopolitical regions

that surround China:

Northeast Asia, Oceania, continental Southeast Asia,

maritime Southeast Asia, South Asia, and Central Asia.

Each of these areas presents complex regional diplomatic and

security problems.

Finally, there is the fourth ring:

the world far beyond China's immediate neighborhood.

China has truly entered this farthest circle only since the late 1990s

and so far for limited purposes:

to secure sources of commodities, such as petroleum;

to gain access to markets and investments;

to get diplomatic support for isolating Taiwan and Tibet's Dalai Lama;

and

to recruit allies for China's positions on international norms and legal regimes.

INSCRUTABLE AMERICA

In Each of China's four security rings,

the United States is omnipresent. It is the most intrusive outside actor

in China's internal affairs, the guarantor of the status quo in Taiwan,

the largest naval presence in the East China and South China seas,

the formal or informal military ally of many of China's neighbors,

and the primary framer and defender of existing international legal regimes.

This omnipresence means that China's understanding of American motives

determines how the Chinese deal with most of their security issues.

Beginning with President Richard Nixon, who visited China in 1972,

a succession of American leaders have assured China of their goodwill.

Every U.S. presidential administration says that China's prosperity and

stability are in the interest of the United States. And in practice,

the United States has done more than any other power to contribute

to China's modernization.

It has drawn China into the global economy;

given the Chinese access to markets, capital, and technology;

trained Chinese experts in science, technology, and international law;

prevented the full remilitarization of Japan;

maintained the peace on the Korean Peninsula;

and helped avoid a war over Taiwan.

Yet Chinese policymakers are more impressed by policies and

behaviors that they perceive as less benevolent.

The American military is deployed all around China's periphery,

and the United States maintains a wide network of defense relationships

with China's neighbors.

Washington continues to frustrate Beijing's efforts

to gain control over Taiwan.

The United States constantly pressures China over its economic policies

and maintains a host of government and private programs that seek

to influence Chinese civil society and politics.

Beijing views this seemingly contradictory set of American actions

through three reinforcing perspectives.

First,

Chinese analysts see their country as heir to an agrarian,

eastern strategic tradition that is pacifistic, defense-minded,

nonexpansionist, and ethical.

In contrast,

they see Western strategic culture - especially that of the United States

- is militaristic, offense-minded, expansionist, and selfish.

Second,

although China has embraced state capitalism with vigor,

the Chinese view of the United States is still informed

by Marxist political thought, which posits that capitalist powers seek

to exploit the rest of the world.

China expects Western powers to resist Chinese competition

for resources and higher-value-added markets.

And although China runs trade surpluses with the United States and

holds a large amount of U.S. debt, China's leading political analysts

believe the Americans get the better end of the deal by using cheap

Chinese labor and credit to live beyond their means.

Third,

American theories of international relations have become popular

among younger Chinese policy analysts, many of whom have earned

advanced degrees in the United States.

The most influential body of international relations theory in China

is so-called offensive realism, which holds that a country will try

to control its security environment to the full extent that its capabilities

permit.

According to this theory, the United States cannot be satisfied

with the existence of a powerful China and therefore seeks to make

the ruling regime there weaker and more pro-American.

Chinese analysts see evidence of this intent in Washington's calls

for democracy and its support for what China sees

as separatist movements in Taiwan, Tibet, and Xinjiang.

Whether they see the United States primarily through a culturalist,

Marxist, or realist lens, most Chinese strategists assume that a country

as powerful as the United States will use its power to preserve and

enhance its privileges and will treat efforts by other countries

to protect their interests as threats to its own security.

This assumption leads to a pessimistic conclusion:

as China rises, the United States will resist.

The United States uses soothing words; casts its actions

as a search for peace, human rights, and a level playing field;

and sometimes offers China genuine assistance.

But the United States is two-faced.

It intends to remain the global hegemon and prevent China

from growing strong enough to challenge it.

In a 2011 interview with Liaowang, a state-run Chinese newsmagazine,

Ni Feng, the deputy director of the Chinese Academy of Social

Sciences' Institute of American Studies, summed up this view.

"On the one hand, the United States realizes that

it needs China's help on many regional and global issues," he said.

"On the other hand, the United States is worried about

a more powerful China and uses multiple means to delay

its development and to remake China with U.S. values."

A small group of mostly younger Chinese analysts

who have closely studied the United States argues that

Chinese and American interests are not totally at odds.

In their view, the two countries are sufficiently remote

from each other that their core security interests need not clash.

They can gain mutual benefit from trade and other common interests.

But those holding such views are outnumbered by strategists

on the other side of the spectrum, mostly personnel from the military

and security agencies, who take a dim view of U.S. policy and

have more confrontational ideas about how China should respond to it.

They believe that China must stand up to the United States militarily

and that it can win a conflict, should one occur, by outpacing U.S.

military technology and taking advantage of what they believe

to be superior morale within China's armed forces.

Their views are usually kept out of sight to avoid frightening

both China's rivals and its friends.

WHO IS THE REVISIONIST ?

To PEER more deeply into the logic of the United States' China strategy,

Chinese analysts, like analysts everywhere, look at capabilities and intentions.

Although U.S. intentions might be subject to interpretation, U.S. military,

economic, ideological, and diplomatic capabilities are relatively easy

to discover - and from the Chinese point of view, they are potentially devastating.

U.S. military forces are globally deployed and technologically advanced,

with massive concentrations of firepower all around the Chinese rim.

The U.S. Pacific Command (PACOM) is the largest of the United States'

six regional combatant commands in terms of its geographic scope and

nonwartime manpower. PACOM'S assets include about 325,000 military

and civilian personnel, along with some 18o ships and 1,90o aircraft.

To the west, PACOM gives way to the U.S. Central Command

(CENTCOM), which is responsible for an area stretching from Central

Asia to Egypt. Before September 11, 2001, CENTCOM had no forces

stationed directly on China's borders except for its training and supply

missions in Pakistan.

But with the beginning of the "war on terror," CENTCOM placed tens

of thousands of troops in Afghanistan and gained extended access

to an air base in Kyrgyzstan.

The operational capabilities of U.S. forces in the Asia-Pacific are

magnified by bilateral defense treaties with Australia, Japan,

New Zealand, the Philippines, and South Korea and cooperative

arrangements with other partners.

And to top it off, the United States possesses some 5,200 nuclear warheads

deployed in an invulnerable sea, land, and air triad.

Taken together, this U.S. defense posture creates what Qian Wenrong

of the Xinhua News Agency's Research Center for International Issue

Studies has called a "strategic ring of encirclement."

Chinese security analysts also take note of the United States' extensive

capability to damage Chinese economic interests.

The United States is still China's single most important market,

unless one counts the European Union as a single entity.

And the United States is one of China's largest sources of foreign

direct investment and advanced technology.

From time to time, Washington has entertained the idea of wielding

its economic power coercively.

After the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, the United States

imposed some limited diplomatic and economic sanctions on China,

including an embargo, which is still in effect, on the sale of

advanced arms.

For several years after that, Congress debated whether to punish China

further for human rights violations by canceling the low

most-favored-nation tariff rates enjoyed by Chinese imports,

although proponents of the plan could never muster a majority.

More recently, U.S. legislators have proposed sanctioning China

for artificially keeping the value of the yuan low to the benefit of

Chinese exporters, and the Republican presidential candidate

Mitt Romney has promised that if elected, he will label China

a currency manipulator on "day one" of his presidency.

Although trade hawks in Washington seldom prevail, flare-ups

such as these remind Beijing how vulnerable China would be

if the United States decided to punish it economically.

Chinese strategists believe that the United States and its allies

would deny supplies of oil and metal ores to China

during a military or economic crisis and that

the U.S. Navy could block China's access to strategically crucial

sea-lanes.

The ubiquity of the dollar in international trade and finance

also gives the United States the ability to damage Chinese interests,

either on purpose or as a result of attempts by the U.S. government

to address its fiscal problems by printing dollars and

increasing borrowing, acts that drive down the value of China's

dollar-denominated exports and foreign exchange reserves.

Chinese analysts also believe that the United States possesses

potent ideological weapons and the willingness to use them.

After World War II, the United States took advantage of its position

as the dominant power to enshrine American principles

in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

and other international human rights instruments

and to install what China sees as Western-style democracies in Japan

and, eventually, South Korea, Taiwan, and other countries.

Chinese officials contend that the United States uses the ideas of

democracy and human rights to delegitimize and destabilize regimes

that espouse alternative values, such as socialism and Asian-style

developmental authoritarianism.

In the words of Li Qun, a member of the Shandong Provincial

Party Committee and a rising star in the Cotrimunist Party,

the Americans' "real purpose is not to proteft so-called human rights

but to use this pretext to influence and limit China's healthy

economic growth and to prevent China's wealth and power

from threatening [their] world hegemony."

In the eyes of many Chinese analysts, since the end of the Cold War

the United States has revealed itself to be a revisionist power

that tries to reshape the global environment even further in its favor.

They see evidence of this reality everywhere: in the expansion of NATO;

the U.S. interventions in Panama, Haiti, Bosnia, and Kosovo;

the Gulf War; the war in Afghanistan; and the invasion of Iraq.

In the economic realm, the United States has tried to enhance

its advantages by pushing for free trade, running down the value of

the dollar while forcing other countries to use it as a reserve currency,

and trying to make developing countries bear an unfair share of

the cost of mitigating global climate change. And perhaps most disturbing

to the Chinese, the United States has shown its aggressive designs

by promoting so-called color revolutions in Georgia, Ukraine, and

Kyrgyzstan.

As Liu Jianfei, director of the foreign affairs division of the Central

Party School of the Chinese Communist Party, wrote in 2005,

"The U.S. has always opposed communist 'red revolutions' and

hates the 'green revolutions' in Iran and other Islamic states.

What it cares about is not 'revolution' but 'color.'

It supported the 'rose,' `orange', and 'tulip' revolutions

because they served its democracy promotion strategy."

As Liu and other top Chinese analysts see it,

the United States hopes "to spread democracy further and

turn the whole globe `blue.

EXPLOITING TAIWAN

Although American scholars and commentators typically see U.S.-Chinese

relations in the postwar period as a long, slow thaw,

in Beijing's view,

the United States has always treated China harshly.

From 1950 to 1972, the United States tried to contain and isolate China.

Among other actions, it prevailed on most of its allies to withhold

diplomatic recognition of mainland China, organized a trade embargo

against the mainland, built up the Japanese military,

intervened in the Korean War,

propped up the rival regime in Taiwan,

supported Tibetan guerillas fighting Chinese control, and

even threatened to use nuclear weapons

during both the Korean War and the 1958 Taiwan Strait crisis.

Chinese analysts concede that

the United States' China policy changed after 1972.

But they assert that

the change was purely the result of an effort to counter the Soviet Union

and, later, to gain economic benefits by doing business in China.

Even then, the United States continued to hedge against China's rise

by maintaining Taiwan as a strategic distraction,

aiding the growth of Japan's military,

modernizing its naval forces,

and pressuring China on human rights.

The Chinese have drawn lessons about U.S. China policy

from several sets of negotiations with Washington.

During ambassadorial talks during the 1950s and 1960s,

negotiations over arms control in the 1980s and 1990s,

discussions over China's accession to the World Trade Organization

in the 1990s,

and negotiations over climate change during the decade that followed,

the Chinese consistently saw the Americans as demanding and unyielding.

But most decisive for Chinese understandings of U.S. policy were

the three rounds of negotiations that

took place over Taiwan in 1971-72, 1978-79, and 1982,

which created the "communiqu - framework" that

governs U.S.Taiwan policy to this day.

When the U.S.-Chinese rapprochement began,

Chinese policymakers assumed that Washington would give up

its support for Taipei in exchange for the benefits of

normal state-to-state relations with Beijing.

At each stage of the negotiations,

the Americans seemed willing to do so.

Yet decades later, the United States remains,

in Beijing's view,

the chief obstacle to reunification.

When Nixon went to China in 1972,

he told the Chinese that he was willing to sacrifice Taiwan

because it was no longer strategically important to the United States,

but that he could not do so until his second term.

On this basis, the Chinese agreed to the 1972 Shanghai Communiqu

-even though it contained a unilateral declaration

by the United States that

"reaffirm[ed] its interest in a peaceful settlement of the Taiwan question,"

which was diplomatic code for a U.S. commitment

to deter any effort by the mainland to take Taiwan by force.

As events played out, Nixon - resigned before he was able

to normalize relations with Beijing, and his successor,

Gerald Ford, was too weak politically to fulfill Nixon's promise.

When the next president, Jimmy Carter, wanted to normalize relations

with China, the Chinese insisted on a clean break with Taiwan.

In 1979, the United States ended its defense treaty with Taiwan

but again issued a unilateral statement restating its commitment

to a "peaceful resolution of the Taiwan issue."

Congress then surprised both the Chinese and the administration

by adopting the Taiwan Relations Act,

which required the United States to "maintain [its] capacity

... to resist any resort to force or other forms of coercion that

would jeopardize the security . . . of the people on Taiwan."

Once again, the deterrent intent was clear.

In 1982, when President Ronald Reagan sought closer relations

with Beijing to ramp up pressure on Moscow,

China prevailed on the United States to sign another communiqu

- which committed Washington to gradually reducing its weapons

sales to Taiwan.

But once the agreement was in place,

the Americans set the benchmark year at 1979,

when arms sales had reached their highest level ;

calculated annual reductions at a small marginal rate,

adjusting for inflation so that they were actually increases ;

claimed that the more advanced weapons systems

that they sold Taiwan were the qualitative equivalents of older systems ;

and allowed commercial firms to cooperate with the Taiwanese

armaments industry under the rubric of technology transfers

rather than arms sales.

By the time President George W. Bush approved a large package

of advanced arms to Taiwan in April 2001,

the 1982 communique was a dead letter.

Meanwhile, as the United States prolonged its involvement with Taiwan,

a democratic transition took place there,

putting unification even further out of Beijing's reach.

Reviewing this history,

Chinese strategists ask themselves why the United States remains

so committed to Taiwan.

Although Americans often argue that they are simply defending

a loyal democratic ally, most Chinese see strategic motives at the root

of Washington's behavior.

They believe that keeping the Taiwan problem going helps

the United States tie China down. In the words of Luo Yuan,

a retired general and deputy secretary-general of the Chinese Society

of Military Science, the United States has long used Taiwan

"as a chess.piece to check China's rise."

THE PERILS OF PLURALISM

THE TAIWAN Relations Act marked the beginning of a trend toward

congressional assertiveness on U.S. China policy, and this continues to

complicate Washington's relationship with Beijing.

Ten years later, the 1989 Tiananmen incident, followed by the end of

the Cold War, shifted the terms of debate in the United States.

China had been perceived as a liberalizing regime;

after Tiananmen, China morphed into an atavistic dictatorship.

And the collapse of the Soviet Union vitiated the strategic imperative

to cooperate with Beijing.

What is more, growing U.S.-Chinese economic ties began to create

frictions over issues such as the dumping of cheap manufactured

Chinese goods on the U.S. market and the piracy of U.S. intellectual

property.

After decades of consensus in the United States, China quickly became

one of the most divisive issues in U.S. foreign policy, partially due to

the intense advocacy efforts of interest groups that make sure

China stays on the agenda on Capitol Hill.

Indeed, since Tiananmen,

China has attracted the attention of more American interest groups

than any other country.

China's political system elicits opposition from human rights organizations ;

its population-control policies anger the antiabortion movement ;

its repression of churches offends American Christians ;

its inexpensive exports trigger demands for protection from organized labor ;

its reliance on coal and massive dams for energy upsets environmental groups ;

and its rampant piracy and counterfeiting infuriate the film, software,

and pharmaceutical industries.

These specific complaints add strength to the broader fear of

a "China threat,"

which permeates American political discourse - a fear that,

in Chinese eyes,

not only denies the legitimacy of Chinese aspirations

but itself constitutes a kind of threat to China.

Of course, there are also those in Congress, think tanks, the media,

and academia who support positions favorable to China,

on the basis that cooperation is important for American farmers,

exporters, and banks, and for Wall Street, or that issues such as

North Korea and climate change are more important than

disputes over rights or religion.

Those advocates may be more powerful in the long run than

those critical of China,

but they tend to work behind the scenes.

To Chinese analysts trying to make sense of the cacophony of views

expressed in the U.S. policy community, the loudest voices are

the easiest to hear, and the signals are alarming.

SUGARCOATED THREATS

In trying to ascertain U.S. intentions, Chinese analysts also look at

policy statements made by senior figures in the executive branch.

Coming from a political system where the executive dominates,

Chinese analysts consider such statements reliable guides to U.S. strategy.

They find that the statements often do two things:

they seek to reassure Beijing that Washington's intentions are benign,

and at the same time, they seek to reassure the American public that

the United States will never allow China's rise to threaten U.S. interests.

This combination of themes produces what Chinese analysts perceive

as sugarcoated threats.

For example, in 2005, Robert Zoellick, the U.S. deputy secretary

of state, delivered a major China policy statement on behalf of

the George W. Bush administration.

He reassured his American audience that the United States would

"attempt to dissuade any military competitor from developing disruptive

or other capabilities that could enable regional hegemony

or hostile action against the United States

or other friendly countries."

But he also explained that China's rise was not a threat

because China

"does not seek to spread radical, anti-American ideologies,"

"does not see itself in a death struggle with capitalism," and

"does not believe that its future depends on overturning the fundamental order

of the international system."

On that basis, he said, the two sides could have "a cooperative relationship."

But cooperation would depend on certain conditions.

China should calm what he called a "cauldron of anxiety" in the United States

about its rise.

It should "explain its defense spending, intentions, doctrine, and

military exercises" ;

reduce its trade surplus with the United States ; and

cooperate with Washington on Iran and North Korea.

Above all, Zoellick advised, China should give up "closed politics."

In the U.S. view, he said,

"China needs a peaceful political transition

to make its government responsible and accountable to its people."

The same ideas have been repeated in slightly gentler language

by the Obama administration.

In the administration's first major policy speech on China, in September 2009,

James Steinberg, then deputy secretary of state,

introduced the idea of "strategic reassurance."

Steinberg defined the principle in the following way :

"Just as we and our allies must make clear that we are prepared

to welcome China's 'arrival' ... as a prosperous and successful power,

China must reassure the rest of the world

that its development and growing global role will not come

at the expense of [the] security and well-being of others."

China would need to "reassure others

that this buildup does not present a threat" ;

it would need to "increase its military transparencyin order to reassure

all the countries in the rest of Asia and

globally about its intentions" and

demonstrate that it "respects the rule of law and universal norms."

To Chinese analysts, such statements send the message that

Washington wants cooperation on its own terms,

seeks to deter Beijing from developing a military capability adequate

to defend its interests, and

intends to promote change in the character of the Chinese regime.

To be sure, Beijing's suspicion of Washington must contend with the fact

that the United States has done so much to promote China's rise.

But for Chinese analysts, history provides an answer to this puzzle.

As they see it, the United States contained China for as long as it could.

When the Soviet Union's rising strength made doing so necessary,

the United States was forced to engage with China in order to reinforce

its hand against Moscow.

Once the United States started to engage with China,

it came to believe that engagement would turn China toward democracy and

would win back for the United States the strategic base on the mainland of

Asia that Washington lost in 1949, when the Communists triumphed

in the Chinese Civil War.

In the Chinese view, Washington's slow rapprochement with Beijing

was not born of idealism and generosity ;

instead,

it was pursued so that the United States could profit from China's

economic opening by squeezing profits from U.S. investments,

consuming cheap Chinese goods, and

borrowing money to support the U.S. trade and fiscal deficits.

While busy feasting at the Chinese table, U.S. strategists overlooked

the risk of China's rise until the late 1990s.

Now that the United States perceives China as a threat,

these Chinese analysts believe,

it no longer has any realistic way to prevent it from continuing to develop.

In this sense, the U.S. strategy of engagement failed,

vindicating the advice of Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping,

who in 1991 advocated a strategy of" hiding our light and

nurturing our strength."

Faced with a China that has risen too far to be stopped,

the United States can do no more than it is doing :

demand cooperation on U.S. terms,

threaten China,

hedge militarily, and

continue to try to change the regime.

HOW DO YOU HANDLE AN OFFENSIVE REALIST ?

Despite these views, mainstream Chinese strategists do not advise China

to challenge the United States in the foreseeable future.

They expect the United States to remain the global hegemon for several

decades, despite what they perceive as initial signs of decline.

For the time being, as described by Wang Jisi, dean of

PekingUniversity's School of International Studies,

"the superpower is more super, and

the many great powers less great."

Meanwhile, the two countries are increasingly interdependent economically

and have the military capability to cause each other harm.

It is this mutual vulnerability that carries the best medium-term hope

for cooperation. Fear of each other keeps alive the imperative to work together.

In the long run, however, the better alternative for both China and the West

is to create a new equilibrium of power that maintains the current world system,

but with a larger role for China.

China has good reasons to seek that outcome.

Even after it becomes the world's largest economy,

its prosperity will remain dependent on the prosperity of its global rivals

(and vice versa), including the United States and Japan.

The richer China becomes, the greater will be its stake in the security of

sea-lanes, the stability of the world trade and financial regimes,

nonproliferation, the control of global climate change, and cooperation

on public health.

China will not get ahead if its rivals do not also prosper.

And Chinese strategists must come to understand that core U.S. interests

- in the rule of law, regional stability, and open economic competition

- do not threaten China's security.

The United States should encourage China to accept this new equilibrium

by drawing clear policy lines that meet its own security needs

without threatening China's.

As China rises, it will push against U.S. power to find the boundaries

of the United States' will.

Washington must push back to establish boundaries for the growth of

Chinese power. But this must be done with cool professionalism,

not rhetorical belligerence.

Hawkish campaign talk about trade wars and strategic competition plays

into Beijing's fears while undercutting the necessary effort to agree

on common interests.

And in any case, putting such rhetoric into action is not a realistic option.

To do so would require a break in mutually beneficial economic ties and

enormous expenditures to encircle China strategically, and it would force

China into antagonistic reactions.

Nevertheless, U.S. interests in relation to China are uncontroversial and

should be affirmed :

a stable and prosperous China,

resolution of the Taiwan issue on terms Taiwan's residents are willing to accept,

freedom of navigation in the seas surrounding China,

the security of Japan and other Asian allies,

an open world economy, and

the protectionof human rights.

The United States must back these preferences with credible U.S. power,

in two domains in particular.

First,

the United States must maintain its military predominance in the western Pacific,

including the East China and South China seas.

To do so, Washington will have to

continue to upgrade its military capabilities,

maintain its regional defense alliances, and

respond confidently to challenges.

Washington should reassure Beijing that these moves are intended

to create a balance of common interests rather than to threaten China.

That reassurance can be achieved by strengthening existing mechanisms

for managing U.S.-Chinese military interactions.

For example, the existing Military Maritime Consultative Agreement

should be used to design procedures that would allow U.S. and Chinese

aircraft and naval vessels to operate safely when in close proximity.

Second,

the United States should continue to push back against Chinese efforts

to remake global legal regimes in ways that do not serve the interests

of the West.

This is especially important in the case of the human rights regime,

a set of global rules and institutions that will help determine the durability

of the liberal world order the United States has long sought to uphold.

China has not earned a voice equal to that of the United States

in a hypothetical Pacific Community or

a role in a global condominium as one member of a "G-2."

China will not rule the world unless the United States withdraws from it,

and China's rise will be a threat to the United States and the world

only if Washington allows it to become one.

For the United States, the right China strategy begins at home.

Washington must sustain the country's military innovation and renewal,

nurture its relationships with its allies and other cooperating powers,

continue to support a preeminent higher-education sector,

protect U.S. intellectual property from espionage and theft,

and regain the respect of people around the world.

As long as the United States addresses its problems at home and

holds tight to its own values, it can manage China's rise.

The End

関連サイト:

1.愛国教育が中国を滅ぼす−憎悪感植え付けが諸悪の根源

2.中国国民のみならず、地球も殺す中国の公害

−09年の温室効果ガス排出量、中国23.7%,米国17.9%,日本3.9%

3.中国の暴力団的海洋制覇は国際平和の敵

4.ダライ・ラマ法王のノーベル平和賞受賞記念講演・チベットにおける中国の残虐行為

5.中国のウイグル人虐殺と迫害、46回もの原爆実験

6.韓国従軍慰安婦問題−日本の誠実な謝罪と膨大な賠償金支払いの

事実を日韓両国国民に知らせよ