-Practice the English Copy-Writing Method Every Day ②

2013年2月 志村英盛

関連サイト:英語脳創りで情報力・発信力を高める-毎日、量聴、量作文、量音読

出典:AERA ENGLISH 2005年3月増刊2/5号(朝日新聞社 発行)第22頁・第23頁(抜粋)

英語脳とは独立した言語中枢

英語を自在に操ることができる人の脳は、できない人の脳とどう違うのか?

植村研一浜松医科大学名誉教授(日本医学英語教育学会名誉理事長)は、

英語を流暢に話す日本語・英語バイリンガルと、英語を話すのが苦手な

日本人大学生の脳内血流を比べる実験をした。

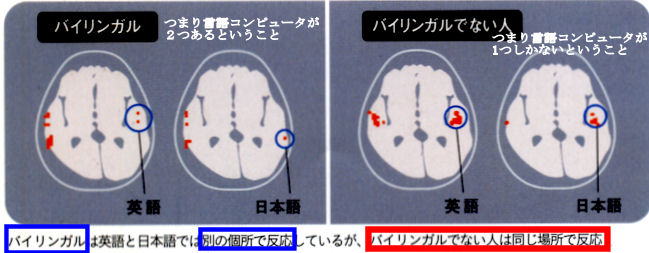

英語のニュースを聞かせると、どちらも、脳の一部に反応を示す血流が

見られる。バイリンガルの脳は血流が2か所に分かれる。日本人大学生の

脳の血流は1か所だけであった。

植村教授によると、血流が見られたのは、言葉を聞いて意味を認識する

ウェルニッケ言語野。日本語と英語を聞いた時、このウェルニッケ言語野で

血流が別々流れるか、同じ個所でしか流れないかが、バイリンガルと、

そうでない人との違いとのことである。

「この血流のある回路が、いわゆる言語中枢です。この言語中枢が、

日本語と英語で、それぞれ独立しているか、否かが、英語脳がつくられて

いるか、否かの違いなのです。」

脳に英語の言語中枢が独立してできると、日本語を介さずに、耳や目から

入ってきた英語を、瞬時に理解するネットワークができる。

英語教育を8年以上受けた大学生でも、ほとんどがネイティブ・スピーカーと

自由に会話することができない。そのわけは、

「英語の言語中枢が形成されていないからです。英語を話せない先生が、

脳の機能を無視して、日本語への翻訳を通して、すなわち、英文和訳、和文

英訳で英語を教えるという英語教育を行っているのが、日本人の大多数が

英語を話せない原因です」と植村教授は指摘する。

脳内部の言語中枢の機能は、脳神経外科医が、腫瘍などを取り除く際、

後遺症が残らないよう、脳内にある機能を調べた結果、分かったものだ。

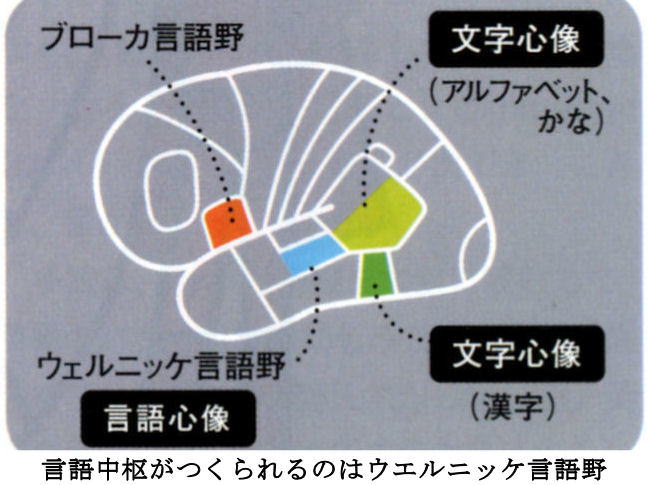

言葉を聞いて意味を察するウェルニッケ言語野、言語を発するブローカ

言語野のほかに、かなを理解する、漢字を理解するなどの部分は、

それぞれ別の場所にあるが、ウェルニッケ言語野が喪失した場合のみ、

言葉そのものが消失し、言語の回復が不可能になるという。

微妙なニュアンスを瞬時に理解できる英語脳をつくる

英語の言語中枢を独立させるには、まず聴きまくることだ。

植村教授は、英語のほか、ドイツ語、フランス語、オランダ語、ロシア語、

イタリア語、ポーランド語、中国語、韓国語、スペイン語、ポルトガル語を

学び、12か国語を自在に操る。50歳を過ぎてから学んだポーランド語も、

学会で研究発表するほどに上達した。秘訣は「3か月間は徹底して聴くこと」だと。

植村教授は、毎日、車の運転をしながら語学の教材を聴く。そのとき、

文字は一切見ない。文字を理解する部分は、言語中枢とは異なる部分なので、

文字に頼ると言語中枢は発達しないからだ。さらにシャドーイングや、

口の形を変えて日本語にない音を意識して出すなどの練習をする。

植村教授は、米国に留学した経験もあり、同時通訳をこなす。

英語論文作成の指導も手がける。植村教授は、医学学会で「英語の達人」

として知られているが、英語脳の仕組みに注目したのは、自身の苦い体験からだ

という。

得意の英語で論文を書き、米国人教授に提出したところ、「君の英語は読める

(readable)けど、しっくりこない(not comfortable)」と指摘された。

文法的には正しくても、真っ赤に直されて返ってきた原稿を見て、英語を

そのままのニュアンスで理解し、表現することの必要性を痛感したとのこと。

英語を聞き、微妙なニュアンスまで瞬時に理解する。これには、独立した

英語言語中枢=英語脳が不可欠である。たとえば、高いところに登って

しまった子ども対して、母親が言う "Honey, please do not move!"。

日本語訳をあてると、「坊や、じっとしてるのよ !」

もし、英語で "Stay still,there.!"と言ってしまったら、子どもはびっくりして、

逆に落っこちてしまうかもしれない。同じ意味でも、肯定形を使うと

英語では強い命令だが、日本語では弱い命令になり、否定形を使うとその逆に

なることや、主語を何にするかなどで、文脈や意味合いが微妙に変わってくる。

この感覚的な選択が自然にできるようになれば、英語脳に近づいたといえるだろう。

植村教授は、「日本人が陥りやすいニュアンスの間違いや音の違いなどは、

ある程度、法則にまとめて防ぐことは可能」と話す。それでも、一度、

原点に立ち返って、英語脳を創ってみてはどうだろうか。

以上

011

The KAIZEN Approach to Problem Solving

『KAIZEN』 Chapter 6

by Masaaki Imai

The Problem in Management

KAIZEN starts with a problem or, more precisely, with the

recognition that a problem exists. Where there are no problems,

there is no potential for improvement. A problem in business

is anything that inconveniences people downstream, either

people in the next process or ultimate customers.

The problem is that the people who create the problem are

not directly inconvenienced by it. Thus people are always

sensitive to problems (or inconveniences created by problems)

caused by other people, yet insensitive to the problems and

the inconveniences they cause other people. The best way

to break the vicious circle of passing the buck from one person

to another is for every individual to resolve never to pass on

a problem to the next process.

In day-to-day management situations, the first instinct,

when confronted with a problem, is to hide it or ignore it

rather than to face it squarely. This happens because a problem

is a problem, and because nobody wants to be accused of

having created the problem. By resorting to positive thinking,

however, we can turn each problem into a valuable opportunity

for improvement. Where there is a problem, there is potential

for improvement. The starting point in any improvement, then,

is to identify the problem. There is a saying among TQC

practitioners in Japan that problems are the keys to hidden

treasure. Yet how many people have the courage to admit that

they have a problem?

I still vividly recall my first sales call twenty-some years ago.

I had just gotten back from a five-year stint with the Japan

Productivity Center in the United States, had hung out my shingle

as a management consultant, and was enthusiastically calling on

prospective clients.

My first call was on Revlon Japan. I had an introduction from

an executive at the head office in New York and had been told that

their man in Tokyo needed some assistance. So, as a novice in the

consulting business, I made a sweeping entrance into the general

manager's office and, as soon as I had introduced myself, started

with, "With regard to your problems in Japan ..." The American

general manager cut me off with a curt, "We have no problems in

Japan." End of interview. I have since become wiser and now never

discuss a client's "problem." It is always the client's

"opportunity for improvement."

It is only human nature not to want to admit that you have

a problem, since admitting to problems is tantamount to confessing

failings or weaknesses. The typical American manager is afraid

people will think he is part of the problem. However, once he

realizes that he has a problem (as most people do), his first

step should be to admit it and to "share" the problem. It is

particularly important that he share the problem with his superiors,

since he usually does not have the resources to solve it alone

and will need company support.

The worst thing a person can do is to ignore or cover up

a problem. When a worker is afraid that his boss will be mad at him

if he finds out a machine is malfunctioning, he may keep on making

the defective parts and hope that nobody will notice. However,

if he is courageous enough, and if his boss is supportive enough,

they may be able to identify the problem and solve it.

A very popular term in Japanese TQC activities is warusa-kagen,

which refers to things that are not really problems but are somehow

not quite right. Left unattended, warusa-kagen may eventually

develop into serious trouble and may cause substantial damage.

In the workplace, it is usually the worker, not the supervisor,

who notices the warusa-kagen.

In the TQC philosophy, the worker must be encouraged to identify

and report such warusa-kagen to the boss, who should welcome

the report. Rather than blame the messenger, management should be glad

the problem was pointed out while it was still minor and should welcome

the opportunity for improvement. In reality,however, many opportunities

are lost simply because neither worker nor management likes problems.

Another point in warusa-kagen is that the problems must be expressed

in quantitative, not qualitative, terms. Many people are uncomfortable

with the effort to quantify. Yet only by analyzing problems in terms

of objective figures can we tackle them in a realistic manner.

When workers are trained to be attentive to warusa-kagen, they also

become attentive to subtle abnormalities developing in the work-shop.

In one Tokai Rika plant, workers reported 534 such subtle abnormalities

in a single year. Some of these irregularities might have led to serious

trouble had they not been brought to management's attention.

Another important aspect of this approach to problems is that most

problems in management occur in cross-functional areas. Good Japanese

managers who have worked at the same company for years and expect

to stay for years more have developed a sensitivity to cross-functional

situations.

(Promotion to important managerial positions should in part be based on

how much sensitivity to cross-functional requirements the employee

develops.)

Information feedback and coordination with other departments is a routine

part of a manager's job.

In many Western companies, however, cross-functional situations are

perceived as conflicts and are addressed from the standpoint of conflict

resolution rather than problem solving. The lack of predetermined criteria

for solving cross-functional problems and the jealously guarded professional

"turf' make the job of solving cross-functional problems all the more

difficult.

KAIZEN and Labor-Management Relations

This may be an appropriate point at which to consider the role

Western trade unions have traditionally played with regard to improvement.

If we take an unbiased look at what unions have been doing in the name

of protecting their members' rights, we find that they have, by obstinately

opposing change, often succeeded only in depriving their members of a chance

for fulfillment, a chance to improve themselves.

By resisting change in the workplace, unions have deprived the workers

of a chance to work better and more efficiently on an improved process

or machine. Workers should welcome being exposed to new skills and

opportunities, because such experience leads to new horizons and challenges

in life. However, when management has suggested such changes as assigning

workers different jobs, the unions have opposed it, arguing that it would lead

to exploitation and would infringe upon the workers' union rights.

Stubbornly preserving the tradition of union membership based upon

particular job skills, union members have been confined to their fragmented

pieces of work and have forfeited precious opportunities to learn and acquire

new skills associated with their work-opportunities to meet new challenges

and to grow as human beings. Such an attitude has often been based on the

union's fear that improvements may result in a decline in membership or

unemployment for its members.

In May 1982, Hajime Karatsu, then managing director of Matsushita

Communication Industrial, gave an address in Washington,D.C., explaining

Japan's successful TQC practices. After this speech, someone asked him

if he thought there was a culture gap between Japan and the United States

that made TQC possible in Japan but not in the United States. Karatsu's

response was:

Before coming to Washington, I stopped off in Chicago to see the Consumer

Electronics Show. There were many Matsushita products on display at the show.

When they arrived packed in crates, it was the work of the carpenters' union

to remove nails from the crates. However, simply taking out the nails was not

enough to remove the entire wooden frame, since there were some nuts and bolts

remaining. The man from the carpenters' union said that it was not his job

to remove the nuts and bolts, and that he would not do it. Finally the frames

were removed, but again the work stopped because the rest had to be done

by a worker from another union. Then we learned that pamphlets ordered from

Japan had arrived. I went to see about them, but there was nobody there from

the right union to unload the packages. We waited for two hours, but no one

showed up. Finally, the truck driver who had delivered the packages gave up

and went back, with the pamphlets still in his truck.

It might seem that there is a cultural pattern here that makes it

impossible to cooperate to get the job done. However, baseball is a very

American game, and I have never seen the first basemen's and second basemen's

unions discussing who should field the ball after the batter hits it. Whoever

can do it does it, and the whole team benefits. In Japanese companies, people

try to achieve the same type of teamwork as on a baseball team.

In 1965, Isetan Department Store, one of the largest department stores

in Japan (6,000 employees), moved to a five-day week for all employees.

At the same time, labor and management agreed that one of the days off should

be used for rest and the other for self-improvement. In fact, a joint

declaration on Isetan's manpower resources development policy was issued

by the company president and the union president. It read:

The Isetan management and union hereby declare that, sharing the same

workplace, we will join hands to develop our natural personalities and

capabilities to the fullest extent in our daily life and to create

an environment conducive to development. The underlying philosophy of this

joint declaration was that

(1) an individual's developing and exercising his skills at work benefits

both the company and the individual and

(2) people are constantly seeking self-improvement, and the real meaning

of equal opportunity is to provide opportunities for growth.

Stealing Jobs

People who are interested in improving their work should take a positive

interest in the upstream processes that provide the material or semifinished

products. They should also take an interest in the downstream processes,

regarding them as their customers and making every effort to pass along only

good materials or products.

As the old saw goes, "You cannot make a good omelette out of rotten eggs."

There is a similar correlation between the individual's job and the jobs of

his co-workers: if one worker is interested in making KAIZEN part of his work,

his fellow workers must also be involved.

Any job involving more than one worker has gray areas that do not belong

to any one individual. Such gray areas must be taken care of by whoever is

at hand. When the worker sticks to his own job description and refuses

to do any more than what is formally required of him, there is little hope

of KAIZEN.

The Japanese worker has been noted for his willingness to take care of

such gray areas. Because of the lifetime-employment system, the Japanese

blue-collar worker does not feel threatened even when other people pitch in

and do part of his job, since it affects neither his income nor his job

security. For the same reason, he is willing to teach workers the skills

that he has acquired on the job. This smooth transfer of skills from one

generation of workers to another has consolidated the solid base of skilled

labor in Japanese industry.

In an environment where job descriptions and manuals dictate every action,

there is little flexibility for workers to engage in such "gray area"

activities. The workers should be trained so that they can work flexibly

in these gray areas, even as they strictly follow the established work

standards in performing the job. Flexibility is further reduced when several

craft unions are involved in the same workplace. In such a case, going too

far into a gray area can easily be construed as "stealing the other guy's

job." In Japan, this would not be stealing but would be a positive and

humane contribution to KAIZEN, viewed as being to everyone's advantage.

There is something dehumanizing about the logic that the only way you can

be assured of a job is to refuse to teach anyone else your skills. We must

create an environment in which improvement is everybody's business and

everyone's concern.

The End

012

Address at Gettysburg

by Abraham Lincoln

Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth

on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and

dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether

that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated,

can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war.

We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final

resting place for those who here gave their lives that that

nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that

we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate - we cannot

consecrate - we cannot hallow - this ground. The brave men,

living and dead, who struggled here have consecrated it far

above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little

note nor long remember what we say here, but it can never

forget what they did here. It is for us, the living, rather

to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who

fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.

It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task

remaining before us - that from these honored dead we take

increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last

full measure of devotion; that we here highly resolve that

these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation,

under God, shall have a new birth of freedom; and that

government of the people, by the people, for the people,

shall not perish from the earth.

The End

013

THE GENERAL THEORY

OF

EMPLOYMENT INTEREST AND MONEY

BY JOHN MAYNARD KEYNES

FELLOW OF KING'S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE

LONDON MACMILLAN & CO LTD

NEW YORK ・ST MARTIN'S PRESS

1954

PREFACE

This book is chiefly addressed to my fellow economists.

I hope that it will be intelligible to others. But its

main purpose is to deal with difficult questions of

theory, and only in the second place with the applications

of this theory to practice. For if orthodox economics is

at fault, the error is to be found not in the superstructure,

which has been erected with great care for logical consistency,

but in a lack of clearness and of generality in the premisses.

Thus I cannot achieve my object of persuading economists

to re-examine critically certain of their basic assumptions

except by a highly abstract argument and also by much

controversy. I wish there could have been less of the latter.

But I have thought it important, not only to explain

my own point of view, but also to show in what respects

it departs from the prevailing theory. Those, who are

strongly wedded to what I shall call "the classical theory",

will fluctuate, I expect, between a belief that I am quite

wrong and a belief that I am saying nothing new.

It is for others to determine if either of these or the

third alternative is right. My controversial passages are

aimed at providing some material for an answer; and I must

ask forgiveness if, in the pursuit of sharp distinctions,

my controversy is itself too keen. I myself held with

conviction for many years the theories which I now attack,

and I am not, I think, ignorant of their strong points.

The matters at issue are of an importance which cannot

be exaggerated. But, if my explanations are right, it is my

fellow economists, not the general public, whom I must first

convince. At this stage of the argument the general public,

though welcome at the debate, are only eavesdroppers

at an attempt by an economist to bring to an issue the deep

divergences of opinion between fellow economists which have

for the time being almost destroyed the practical influence

of economic theory, and will, until they are resolved,

continue to do so.

The relation between this book and my Treatise on Money,

which I published five years ago, is probably clearer to myself

than it will be to others; and what in my own mind is a natural

evolution in a line of thought which I have been pursuing

for several years, may sometimes strike the reader as a confusing

change of view. This difficulty is not made less by certain changes

in terminology which I have felt compelled to make. These changes

of language I have pointed out in the course of the following

pages; but the general relationship between the two books can be

expressed briefly as follows. When I began to write my Treatise

on Money I was still moving along the traditional lines of regarding

the influence of money as something so to speak separate from

the general theory of supply and demand. When I finished it, I had

made some progress towards pushing monetary theory back to becoming

a theory of output as a whole. But my lack of emancipation from

preconceived ideas showed itself in what now seems to me to be

the outstanding fault of the theoretical parts of that work

(namely, Books III and IV), that I failed to deal thoroughly

with the effects of changes in the level of output. My so-called

"fundamental equations" were an instantaneous picture taken on the

assumption of a given output. They attempted to show how, assuming

the given output, forces could develop which involved a

profit-dis-equilibrium, and thus required a change in the level of

output. But the dynamic development, as distinct from the instantaneous

picture, was left incomplete and extremely confused. This book,

on the otherhand, has evolved into what is primarily a study of

the forces which determine changes in the scale of output and

employment as a whole; and, whilst it is found that money enters

into the economic scheme in an essential and peculiar manner,

technical monetary detail falls into the background. A monetary

economy, we shall find, is essentially one in which changing views

about the future are capable of influencing the quantity of employment

and not merely its direction. But our method of analysing the economic

behaviour of the present under the influence of changing ideas about

the future is one which depends on the interaction of supply and demand,

and is in this way linked up with our fundamental .theory of value.

We are thus led to a more general theory, which includes the classical

theory with which we are familiar, as a special case.

The writer of a book such as this, treading along unfamiliar paths,

is extremely dependent on criticism and conversation if he is to avoid

an undue proportion of mistakes. It is astonishing what foolish things

one can temporarily believe if one thinks too long alone, particularly

in economics (along with the other moral sciences), where it is often

impossible to bring one's ideas to a conclusive test either formal or

experimental. In this book, even more perhaps than in writing my Treatise

on Money, I have depended on the constant advice and constructive

criticism of Mr.R. F. Kahn. There is a great deal in this book which

would not have taken the shape it has except at his suggestion. I have

also had much help from Mrs.Joan Robinson, Mr. R. G. Hawtrey and

Mr. R. F.Harrod, who have read the whole of the proof-sheets.

The index has been compiled by Mr. D. M. Bensusan-Butt of King's College,

Cambridge.

The composition of this book has been for the author a long struggle

of escape, and so must the reading of it be for most readers if the

author's assault upon them is to be successful - a struggle of escape

from habitual modes of thought and expression. The ideas which are here

expressed so laboriously are extremely simple and should be obvious.

The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old

ones, which ramify, for those brought up as most of us have been,

into every corner of our minds.

J. M. KEYNES

December 13, I935

The End

014

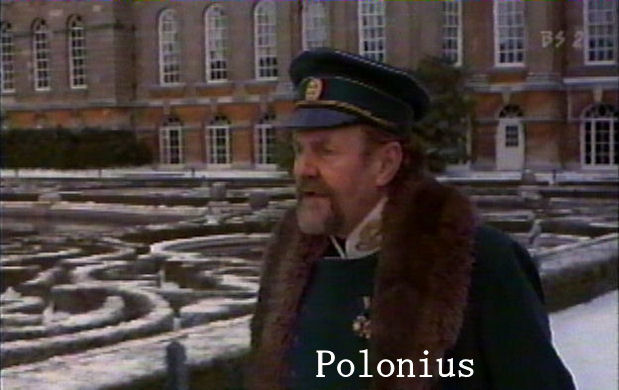

Hamlet

by William Shakespeare

Scene III

Elsinore. The house of Polonius.

[Enter LAERTES and OPHELIA his sister.]

Laertes

My necessaries are embark'd. Farewell. And,

sister, as the winds give benefit

And convoy is assistant, do not sleep,

But let me hear from you.

Ophelia

Do you doubt that?

Laertes

For Hamlet, and the trifling of his favour,

hold it a fashion and a toy in blood,

a violet in the youth of primy nature,

forward not permanent, sweet not lasting,

the perfume and suppliance of a minute;

no more.

Ophelia

No more but so?

Laertes

Think it no more;

for nature crescent does not grow alone.

In thews and bulk, but as this temple waxes,

the inward service of the mind and soul

grows wide withal.

Perhaps he loves you now,

and now no soil nor cautel doth besmirch

the virtue of his will; but you must fear,

his greatness weigh'd, his will is not his own;

for he himself is subject to his birth:

he may not, as unvalued persons do,

carve for himself; for on his choice depends

the sanity and health of this whole state;

and therefore must his choice be circumscrib'd

unto the voice and yielding of that body

whereof he is the head.

Then if he says he loves you,

it fits your wisdom so far to believe it

as he in his particular act and place

may give his saying deed; which is no further

than the main voice of Denmark goes withal.

Then weigh what loss your honour may sustain,

if with too credent ear you list his songs,

or lose your heart, or your chaste treasure open

to his unmast'red importunity.

Fear it, Ophelia, fear it, my dear sister;

and keep you in the rear of your affection,

out of the shot and danger of desire.

The chariest maid is prodigal enough

if she unmask her beauty to the moon.

Virtue itself scapes not calumnious strokes;

the canker galls the infants of the spring

too oft before their buttons be disclos'd;

and in the morn and liquid dew of youth

contagious blastments are most imminent.

Be wary, then; best safety lies in fear:

Youth to itself rebels, though none else near.

Ophelia

I shall the effect of this good lesson keep

as watchman to my heart.

But, good my brother, do not, as some ungracious

pastors do.

Show me the steep and thorny way to heaven,

whiles, like a puff'd and reckless libertine.

Himself the primrose path of dalliance treads

and recks not his own rede.

Laertes

0, fear me not !

[Enter POLONIUS.]

I stay too long. But here my father comes.

A double blessing is a double grace;

Occasion smiles upon a second leave.

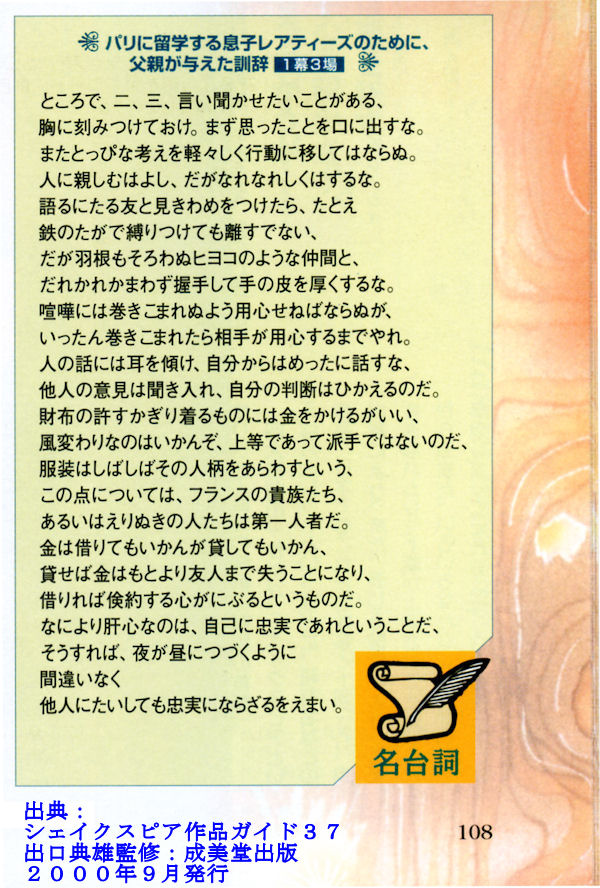

Polonius

Yet here, Laertes! Aboard, aboard, for shame !

The wind sits in the shoulder of your sail,

and you are stay'd for. There - my blessing

with thee !

And these few precepts in thy memory

look thou character.

Give thy thoughts no tongue,

Nor any unproportion'd thought his act.

Be thou familiar, but by no means vulgar.

Those friends thou hast, and their adoption tried,

grapple them to thy soul with hoops of steel;

But do not dull thy palm with entertainment

of each new-hatch'd, unfledg'd courage.

Beware of entrance to a quarrel;

but, being in, bear't that th' opposed may beware of thee.

Give every man thy ear, but few thy voice;

take each man's censure, but reserve thy judgment.

Costly thy habit as thy purse can buy,

but not express'd in fancy; rich, not gaudy;

for the apparel oft proclaims the man;

and they in France of the best rank and station

are of a most select and generous choice in that.

Neither a borrower nor a lender be;

for loan oft loses both itself and friend,

and borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry.

This above all - to thine own self be true,

and it must follow, as the night the day,

thou canst not then be false to any man.

Farewell; my blessing season this in thee !

Laertes

Most humbly do I take my leave, my lord.

Polonius

The time invite's you; go, your servants tend.

Laertes

Farewell, Ophelia; and remember well

what I have said to you.

Ophelia

'Tis in my memory lock'd,

and you yourself shall keep the key of it.

Laertes

Farewell.

[Exit.]

The End

015

Company Philosophy:

The Way We Do Things around Here

The Will to Manage Chaptr 2

by Marvin Bower

Managing Director,McKinsey & Company,Inc

I have an abstract painting in my office that I bought

in London off the Piccadilly fence. In that open-air mart,

which operates on weekends, the artists sell their own works.

Judged by the $43 price, my painting is not great art.

But it has delightful swirls, angles, and other abstract

forms, all in bright colors. And when Mr. Eves, the artist,

told me the title - "Forces at Work" - I bought it immediately.

With a little metal plate bearing the title and the artist's

name, the painting is a constant reminder to me that any

successful organization must give continuing attention

to keeping adjusted to the forces affecting it - that is,

to the forces-at-work element of its philosophy. But before

discussing that element, let us examine the whole concept of

company philosophy as a system component and identify other

important elements of a successful philosophy.

Meaning and Elements of Company Philosophy

Over the years, I have noticed that some executives -

particularly top-management executives in the most successful

companies - frequently refer to "our philosophy." They may speak

of something that "our philosophy calls for," or of some action

taken in the business that is "not in accordance with our

philosophy." In mentioning "our philosophy," they assume that

everyone knows what "our philosophy" is.

As the term is most commonly used, it seems to stand for

the basic beliefs that people in the business are expected

to hold and be guided by - informal, unwritten guidelines'

on how people should perform and conduct themselves. Once such

a philosophy crystallizes, it becomes a powerful force indeed.

When one person tells another, "That's not the way we do things

around here," the advice had better be heeded. And when

a superior says that to a subordinate, it had better be taken

as an order.

In dealing with the concept as I find it used in practice

by leading executives, the literature on company philosophy is

neither very extensive nor very satisfactory. But one dictionary

definition of philosophy does apply: "general laws that furnish

the rational explanation of anything." In this sense, a company

philosophy evolves as a set of laws or guidelines that gradually

become established, through trial and error or through

leadership, as expected patterns of behavior.

In discussing the philosophy of International Business

Machines Corporation, Thomas J. Watson, Jr., the chairman,

says:

I firmly believe that any organization, in order to survive

and achieve success, must have a sound set of beliefs

on which it premises all its policies and actions.

Next, I believe that the most important single factor in

corporate success is faithful adherence to those beliefs... .

In other words, the basic philosophy, spirit and drive of an

organization have far more to do with its relative achievements

than do technological or economic resources, organizational

structure, innovation and timing. All these things weigh heavily

on success. But they are, I think, transcended by how strongly

the people in the organization believe in its basic precepts and

how faithfully they carry them out.'

Some typical examples of basic beliefs that serve as guidelines

to action will clarify the concept. Although such basic beliefs

inevitably vary from company to company, here are five that I find

recurring frequently in the most successful corporations:

1. Maintenance of high ethical standards in external and

internal relationships is essential to maximum success.

2. Decisions should be based on facts, objectively considered

- that I call the fact-founded, thought-through approach to

decision making.

3. The business should be kept in adjustment with the forces

at work in its environment.

4. People should be judged on the basis of their performance,

not on nationality, personality, education, or personal traits

and skills.

5. The business should be administered with a sense of com-

petitive urgency.

These five common-denominator elements - combined with

other beliefs - are informal supplements to the more formal

processes of management. A brief discussion of each will show

how useful and how powerful a company philosophy can be,

once it provides effective guidelines for "the way we do things

around here."

High Ethical Standards

In dealing with the value of high ethical standards in a

business, I don't want to belabor the obvious. But I do want to

point up a few nuances that sometimes escape even executives

of high principle.

Since the whole purpose of a system of management is to

inspire and require people to carry out company strategy by

following policies, procedures, and programs, no management

should overlook the set of built-in guidelines that every employee

with a good family background brings to the job. Since anyone

who has been well trained in Judaic-Christian ethics instinctively

acts in accordance with those principles, it is sheer

shortsightedness for any management to overlook the great practical

value of these powerful guidelines of conduct.

The business with high ethical standards has three primary

advantages over competitors whose standards are lower:

①

A business of high principle generates greater drive and

effectiveness because people know that they can do the right

thing decisively and with confidence. When there is any doubt

about what action to take, they can rely on the guidance of

ethical principles. I can think of three companies - the leaders

in their respective industries - whose inner administrative drive

emanates largely from the fact that everyone feels confident that

he can safely do the right thing immediately. And he also knows

that any action which is even slightly unprincipled will be

generally condemned.

②

A business of high principle attracts high-caliber people

more easily, thereby gaining a basic competitive and profit

edge. A high-caliber person, because he prefers to associate with

people he can trust, favors the business of principle; and he

avoids the employer whose practices are questionable. So, in taking

his first job or in changing jobs, he takes the trouble to find out.

For this reason, companies that do not adhere to high ethical

standards must actually maintain a higher level of compensation

to attract and hold people of ability. A few large companies have

to "reach" for able people with higher compensation simply

because low standards of relationships among people produce

a "jungle" atmosphere in which it is less agreeable to work.

③

A business of high principle develops better and more profitable

relations with customers, competitors, and the general public,

because it can be counted on to do the right thing at all times.

By the consistently ethical character of its actions, it builds

a favorable image. In choosing among suppliers, customers resolve

their doubts in favor of such a company. Competitors are

less likely to comment unfavorably on it. And the general public

is more likely to be open-minded toward its actions and receptive

to its advertising and other communications.

Consider the example of Avon Products, Inc., the house-to-house

cosmetics business. Since 1954 Avon's net profit has been

increasing at an average of over 19 percent a year, compounded,

and in 1963 its return on investment reached 34 percent. According

to an article in the December 1964 issue of Fortune, Avon's founder,

David H. McConnell, "was resolved to be different from the swarms

of itinerant peddlers who were at that time selling goods of

indifferent quality to housewives, and then moving on, rarely

to be seen again." The founder's son carried on his father's belief

in high principle. Citing comments by competitors and suppliers

on the company's high ethical standards, the article notes that

Avon's present chairman, John A.Ewald, its president, Wayne Hicklin,

and a top-management executive now deceased "did a great deal

to ensure that the McConnells' high ethical standards would

continue to be diffused throughout the organization as it expanded."

There should be no need to dwell on these well-recognized

values. But too often, I find, they tend to be taken for granted.

My point in mentioning them is to urge executives to actively

seek ways of making high principle a more explicit element in

their company philosophy. No one likes to declaim about his

honesty and trustworthiness; but the leaders of a company can

profitably articulate, within the organization, their determination

that everyone shall adhere to high standards of ethics. That is

the best foundation for a profit-making company philosophy and

a profitable system of management.

The End

016

Sense of Competitive Urgency and

Developing a Company Philosophy

The Will to Manage Chaptr 2

by Marvin Bower

Managing Director,McKinsey & Company,Inc

Sense of Competitive Urgency

Based on my own comparisons of the administration of leading

American and British companies, I believe that the greater

management effectiveness achieved by leading American companies

is due chiefly to the greater sense of competitive urgency

that pervades our most successful businesses. Addressing

the Industrial Copartnership Association in London, in 1961, H.R.H.

The Duke of Edinburgh put it this way: "Foreign competition is real;

it is going to get tougher, so that if we want to be prosperous

we have simply got to get down to it and work for it.

The rest of the world most certainly does not owe us a living."

Certainly management technique is less important than

competitive urgency. Even the most advanced management methods

will not be fully effective unless these techniques are adopted

and administered with a sense of competitive urgency.

Talking to an international management congress,

the late Charles E. Wilson, then president of GM, put it this way:

Too frequently visitors to America are overly impressed by

our assembly lines and our progressive mass-production

manufacturing methods and are inclined to think that the physical

organization of the work is the essence of our American production

system. They will be confusing the form with the substance

if they believe that simply by installing assembly lines

and progressive manufacturing they will automatically get the

same efficient production and low cost that American industry

achieves. If they do not understand and apply the other

fundamentals of our system at the same time, they will be

greatly disappointed with the results they get... .

The first essential of our American industrial system is

the acceptance by Americans of competition. The responsibility

for individual competition as well as competition between

companies and business organizations stimulates the millions of

Americans to contribute to better ways of doing things and to

accomplish more with the same amount of human effort.*

What can the leaders of a business do to develop a sense of

competitive urgency? In addition to their alertness to external

forces at work, here are the chief characteristics of competitive

top-management executives as I have observed them in action:

1.

The competitive executive gets on with it. He treats time

as his most valuable commodity and paces himself accordingly.

He does not "fiddle around." At the same time, he works with

calm purposefulness, rather than frantic haste.

2.

The competitive executive works with zest. Typically, he works

harder and more effectively than his subordinates. He sets

a good example in work habits, not for the sake of setting

an example but because he has a real zest for his job.

3.

The competitive executive is decisive. After getting the facts

and thinking the problem or decision through, he makes

a considered decision. He recognizes that he will make mistakes,

but he knows that his competitors will, too; and he prefers risk

of error to unnecessary delay. He knows he can safely be wrong

part of the time, provided he keeps alert to opportunities

for correcting errors.

I recall an executive who habitually made instant decisions

that were not always sound. In talking with him, I discovered

that just after graduating from college, he had spent a year

as a minor-league baseball umpire. So he fell into the habit of

making business decisions with nearly the same speed.

Once aware of this, he realized that an executive - unlike

an umpire - has an opportunity to gather and consider facts,

to change his mind, and to correct his mistakes. So he began

taking a little longer to think decisions through - and raised

his batting average considerably.

4.

The competitive executive seizes and exploits opportunities.

He is more interested in building on strength than in shoring

up weaknesses. He devotes more time to building his own

company's position than to countering competitive moves.

Therefore, a system for managing appeals to him.

5.

The competitive executive seeks out and faces up to problems.

He knows that the passage of time usually makes a tough

problem even harder to solve. But when it cannot be solved

immediately, he turns to developing company strengths and works

around the problem while waiting for a better time to solve it.

6.

The competitive executive does not shrink from difficult

personnel decisions. He knows that unless poor performance can

be overcome (as it often can), it is fairer to the company and

the individual to remove him sooner rather than later.

But the competitive executive is fair and not ruthless.

He knows a management system will not be effective unless

it facilitates fair and sound decisions affecting people.

Fair decisions concerning people are often received

surprisingly well even by the person who is adversely affected.

I recall the case of the leading salesman of a large industrial

products company who spent much of his time at race tracks.

Because of the large orders the marketing director thought

the salesman controlled, for many years no action was taken

to replace him. When a new marketing executive finally dismissed

him, the salesman said he wondered why the action had not been

taken long before. Of course, customer respect for the company

increased, and no orders were lost.

7.

The competitive executive focuses on increasing the company's

share-of-market at a profit. His every action is directed

toward building a stronger competitive position for the long term;

but he takes the action now.

These are some of the characteristics of the executive who

possesses a sense of competitive urgency. This incessant drive

"to get on with it now" is necessary to succeed in our competitive

profit-and-loss economy. More than management techniques,

it makes our system the best means yet discovered for fulfilling

people's material wants and needs profitably and for providing

the psychic benefits of work itself. But that drive can be made

more purposeful and effective by a management system. In turn,

a management system helps develop a sense of competitive urgency.

The interaction increases the likelihood of success for any enterprise.

Developing a Company Philosophy

In discussing the need for developing a company philosophy,

rather than just letting it happen, I have selected from successful

company experience just five common elements that make a good

philosophical foundation for any business. To them, the management

of any company or division can add other beliefs that should guide

the organization. If they are to be a real part of the philosophy,

however, these beliefs should be basic enough to become overriding

guidelines to action.

Even without planning or specific effort, any company will gradually

develop a philosophy as people observe and learn through trial and

error "the way we do things around here." However, it is my conviction

that a positive program by top management to build or reshape a sound

fundamental philosophy should be the underlying and overriding

component of the company's system of management.

Whatever beliefs top management wants to build into its philosophy

must, of course, be demonstrated in practice if they are to take firm

root in the minds of people throughout the organization. But to make

the guidelines really operative, something more is needed than

the power of example. Executives and supervisors at all levels

should articulate the company philosophy, relate it to actual situations

and problems at hand, and point out to subordinates where their actions

square, or fail to square, with the beliefs of the organization.

It is through this kind of leadership that a company philosophy

for success can be most soundly and securely built.

Deeply and widely held beliefs in "the way we do things around here"

provide a solid foundation on which to erect a programmed management

system. And these beliefs interact with other system components

to give them strength and to gain strength from them. This is especially

true of the next component I discuss: strategic planning.

The End

017

The Good Earth

by Pearl S. Buck

1.The Plot

Pearl Buck's The Good Earth opens with Wang Lung,

a poor Chinese farmer, making the preparations for his wedding day.

To mark the momentous change in his life, he bathes for the first time

since the New Year, dresses in his best clothes, and buys extra food

at the market.

He goes to the House of Hwang, where his new wife has worked

as a slave, to collect her. Although his new wife, 0-lan, is not beautiful,

and her feet have not been bound, he is pleased that she has neither

pockmarks nor a split lip. Back at his modest house he hosts a wedding

feast, and she impresses him with her cooking skills, making a meal more

delicious than Wang has ever tasted.

Wang's marriage brings good fortune. 0-lan's arrival restores order and

comfort to the house; she works hard in the fields and soon gives birth

to a son. Wang's crops are plentiful, and when the New Year arrives,

0-lan and Wang take their son to the Great House (the House of Hwang),

where 0-lan presents her healthy son to her former mistress.

Because of their good fortune, Wang has enough silver to buy land from

the Great House, which has fallen on hard times. For several more years,

Wang and 0-lan thrive. 0-lan brings a second son and a daughter into

the world, and Wang continues to buy land from the increasingly decadent

House of Hwang.

Their luck turns, however, with the beginning of a severe drought.

Starvation drives them to desperate measures and sets the villagers

at each other's throats. Finally Wang and his family head south for the city,

where there is the promise of food, using the last of their money to buy

railroad passage.

Life in the city brings little improvement - but at least there is food.

Wang, his wife, his father, and their three children live in a shack and buy

their meals for pennies in the great public kitchens of the city. Wang pulls

a rick-shaw, and 0-lan and her children beg for money. Wang dreams

constantly of returning to the land. Finally a war breaks out in the city,

the wealthy families flee, and by stealing from the rich, Wang and 0-lan

are able to return to their land and rebuild their farm.

The family's fortunes improve and more children are born. Despite a flood

that submerges his fields, Wang's financial power increases. He grows

restless and dissatisfied with his wife and falls under the spell of a woman

called Lotus Flower, who becomes his concubine. But Lotus Flower does

not bring him happiness, and Wang is plagued by turmoil in his household.

Both 0-lan and his father die, and his sons lack interest in the rural

empire he has built. In the end, it is clear that his obsession with the land

will not outlive him, and all he has worked to build will disappear after his

death.

2.Characters

Wang Lung

A poor farmer at the beginning and a wealthy landowner by the end

of the novel, Wang holds steadfast to the belief that everything comes

from the good earth. He is not immune to earthy temptations, and

he allows his sons to become further and further removed from their

agricultural roots, but working the land always helps to restore him.

0-lan

The stoic, hardworking, and self-sacrificing wife of Wang Lung.

Formerly a slave in the Great House, she is extremely proud that she

has married and brought sons into her husband's family. A woman of

few words, she is thoughtful, persuasive, and wise. Wang begins to

appreciate her value only after her death.

Wang Lung's Father

An infirm old man who wants nothing more than to have a cup of hot

water in the morning and grandsons to warm his heart, Wang Lung's

father has few responsibilities. He refuses to beg in the great city, and

he does not help with the farmwork. He does, however, greatly disapprove

of his son's having taken a concubine.

Wang Lung's Oldest Son

Educated, moody, and overly concerned with the social standing of the

family, Wang Lung's oldest son exhibits all of the characteristics of the

privileged class. He takes great pride in restoring the House of Hwang -

and spending the family money freely.

Wang Lung's Oldest Daughter

Referred to as the "poor fool," the oldest daughter was born before

the famine and appears to suffer from mental disabilities. Though Wang

Lung initially resents her, he grows very fond of her.

Wang Lung's Second Son

Wang Lung's second son is frugal and practical. He receives an education,

becomes a merchant, and oversees the business side of his father's farms.

He chooses a wife from a farming family; he also reaffirms his differences

from his brother.

Wang Lung's Uncle

Lazy and corrupt, Wang Lung's uncle borrows money from his nephew,

attempts to swindle him out of his land, and eventually moves his family

into Wang Lung's house. His association with notorious robbers allows him

to manipulate Wang, but his power wanes when he becomes addicted to

opium.

Wang Lung's Aunt

The opposite of 0-lan, Wang Lung's aunt possesses no domestic skills

and allows her children to run wild. She helps arrange for Lotus Flower

to move into Wang Lung's house. Like her husband, she succumbs to opium.

Wang Lung's Nephew

A rebellious young man with unwholesome appetites. He joins the army.

Lotus Flower

Dainty and withholding, Lotus Flower works as a prostitute in a teahouse,

where she casts a spell over Wang Lung. Later she becomes his much-

spoiled concubine.

3.Questions for Discussion

When The Good Earth was published, some critics called it a universal

story. Is the story of The Good Earth still universal at the beginning of

the twenty-first century? What is a "universal story"?

Pearl Buck was an early advocate for women's rights and feminism.

How are women depicted in The Good Earth ? In what ways, if any,

do you see feminist beliefs at work in this novel?

Do the events that unfold in The Good Earth make its title a true

statement or an ironic one ? Is the earth really good or not ?

In what ways ?

Chance plays a critical role in The Good Earth. If 0-lan had not chanced

upon the jewels in the wealthy family's house in the South, Wang Lung would

not have been able to purchase more land when they returned to their

farm. At the same time, Wang Lung believes in the virtue of hard work and

the reward of effort, which is essentially a cause-and-effect view of the

world. What does the novel ultimately say about chance versus causality ?

Writing about people of a different race or nationality can often pose

problems for authors. How would you characterize Buck's depictions of

Chinese farmers ? Does she stereotype them ? Or does she portray them

as complex individuals ? Is it possible to do something in between ?

Practices such as infanticide or taldng a concubine are very foreign and,

for many western readers, distressing. How does Buck help you understand

the complexity of these practices ? Can you think of things that we do

in our culture that would probably appear strange to people from different

countries ?

Although The Good Earth won the Pulitzer Prize in 1932 and was

instrumental in helping Buck receive the Nobel in 1938, the novel lapsed

into obscurity for many years. In what ways do you think this novel is or

is not a classic ? Why is it important (or not important) to read novels

that were prize-winning best sellers during earlier times in our history ?

The End

018

My Fair Lady

Chapter 9 Where Are My Slippers ?

by Alan Jay Lerner

Higgins was outside his house in Wimpole Street late that afternoon.

He couldn't stop thinking about Eliza. Now he knew that he wanted

her with him. She was part of his world.

(singing)

I've grown accustomed to her face!

She almost makes the day begin.

I've grown accustomed to the tune

She whistles night and noon.

He couldn't stop thinking about Eliza・・・

「 I've grown accustomed to her face ! 」

(singing)

Her smiles. Her frowns.

Her ups, her downs,

Are second nature to me now;

Like breathing out and breathing in.

I was serenely independent and content before we met;

Surely I could always be that way again ・and yet

I've grown accustomed to her looks;

Accustomed to her voice:

Accustomed to her face.

He stopped singing. 「 Marry Freddy ! 」 he said angrily.

「 What a stupid idea ! What a heartless thing to do !

She won't be happy. She'll come knocking on my door

one night ・・・ I'm really a most forgiving man ・・・

but I'll never take her back ! Never ! Marry Freddy ! Ha ! 」

He took his key out of his pocket but suddenly stopped.

He did not know quite what to do without Eliza. He needed her.

He was in his work-room that evening, but he couldn't work.

He walked round and round the room. He stopped next to

his recording machine and turned it on. Eliza's voice

came out into the room. He sat down with his back to the

machine and listened, his head down.

「 I want to be a lady in a flower shop 」, her voice said,

「 instead of selling flowers at the corner of Tottenham

Court Road. He said he could teach me, but he bullies me

all the time. 」

Very softly Eliza walked into the room behind him.

She stood looking at him. 「 She was so wonderfully low,

so terribly dirty 」, Higgins said sadly to himself,

remembering her first visit to this room.

「 I washed my face and hands before I came, you know. 」

Eliza said.

Eliza turned off the machine. 「 I washed my face and hands

before I came, you know 」 she said.

Higgins sat up straight in his chair. Most of all he wanted

to laugh loudly, to run to her. Instead, he sat back

in the chair again, pushed his hat down over his eyes and

very softly said, 「 Eliza, where are my slippers ? 」

Eliza wanted to cry. She understood him so well.

The End

参考You Tube :My Fair Lady

019

The Moon and Sixpence

Chapter XIX

by Somerset Maugham

Chapter XIX

I had not announced my arrival to Stroeve, and when I rang

the bell of his studio, on opening the door himself, for a moment

he did not know me. Then he gave a cry of delighted surprise and

drew me in. It was charming to be welcomed with so much

eagerness. His wife was seated near the stove at her sewing, and

she rose as I came in. He introduced me.

'Don't you remember ?' he said to her. 'I've talked to you

about him often.' And then to me: 'But why didn't you let me know

you were coming ? How long have you been here ? How long are you

going to stay ? Why didn't you come an hour earher, and we would

have dined together ?'

He bombarded me with questions. He sat me down in a chair,

patting me as though I were a cushion, pressed cigars upon me,

cakes, wine. He could not leave me alone. He was heart-broken

because he had no whisky, wanted to make coffee for me,

racked his brain for something he could possibly do for me, and

beamed and laughed, and in the exuberance of his delight sweated

at every pore.

'You haven't changed', I said, smiling, as I looked at him.

He had the same absurd appearance that I remembered. He was

a fat little man, with short legs, young still - he could not have been

more than thirty - but prematurely bald. His face was perfectly round,

and he had a very high colour, a white skin, red cheeks, and red lips.

His eyes were blue and round too, he wore large gold-rimmed

spectacles, and his eyebrows were so fair that you could not see them.

He reminded you of those jolly, fat merchants that Rubens painted.

When I told him that I meant to live in Paris for a while, and had

taken an apartment, he reproached me bitterly for not having

let him know. He would have found me an apartment himself, and

lent me furniture - did I really mean that I had gone to the expense

of buying it ? - and he would have helped me to move in. He really

looked upon it as unfriendly that I had not given him the opportunity

of making himself useful to me. Meanwhile, Mrs Stroeve sat quietly

mending her stockings, without talking, and she listened to all he said

with a quiet smile on her lips.

'So, you see, I'm married', he said suddenly; 'what do you think of

my wife?'

He beamed at her, and settled his spectacles on the bridge of his

nose. The sweat made them constantly slip down.

'What on earth do you expect me to say to that?' I laughed.

'Really, Dirk', put in Mrs Stroeve, smiling.

'But isn't she wonderful? I tell you, my boy, lose no time;

get married as soon as ever you can. I'm the happiest man alive.

Look at her sitting there. Doesn't she make a picture? Chardin,

eh ? I've seen all the most beautiful women in the world;

I've never seen anyone more beautiful than Madame Dirk Stroeve.'

'If you don't be quiet, Dirk, I shall go away.'

'Mon petit chou', he said.

She flushed a little, embarrassed by the passion in his tone.

His letters had told me that he was very much in love with his wife,

and I saw that he could hardly take his eyes off her. I could not

tell if she loved him. Poor pantaloon, he was not an object to excite

love, but the smile in her eyes was affectionate, and it was possible

that her reserve concealed a very deep feeling.

She was not the ravishing creature that his love-sick fancy saw,

but she had a grave comeliness. She was rather tall, and her grey

dress, simple and quite well-cut, did not hide the fact that her figure

was beautiful. It was a figure that might have appealed more to

the sculptor than to the costumier. Her hair, brown and abundant,

was plainly done, her face was very pale, and her features were good

without being distinguished. She had quiet grey eyes.

She just missed being beautiful, and in missing it was not even pretty.

But when Stroeve spoke of Chardin it was not without reason, and

she reminded me curiously of that pleasant house-wife in her mob-cap

and apron whom the great painter has immortalized. I could imagine her

sedately busy among her pots and pans, making a ritual of her household

duties, so that they acquired a moral significance; I did not suppose

that she was clover or could ever be amusing, but there was something

in her grave intentness which excited my interest. Her reserve was not

without mystery. I wondered why she had married Dirk Stroeve.

Though she was English, I could not exactly place her, and it was not

obvious from what rank in society she sprang, what had been her

upbringing, or how she had lived before her marriage. She was very silent,

but when she spoke it was with a pleasant voice, and her manners were

natural.

I asked Stroeve if he was working.

'Working ? I'm painting better than I've ever painted before.'

We sat in the studio, and he waved his hand to an unfinished picture

on an easel. I gave a little start. He was painting a group of Italian

peasants, in the costume of the Campagna, lounging on the steps of

a Roman church.

'Is that what you're doing now?' I asked.

'Yes. I can get my models here just as well as in Rome.'

'Don't you think it's very beautiful ?' said Mrs Stroeve.

'This foolish wife of mine thinks I'm a great artist', said he.

His apologetic laugh did not disguise the pleasure that he felt.

His eyes lingered on his picture. It was strange that his critical

sense, so accurate and unconventional when he dealt with the

work of others, should be satisfied in himself with what was

hackneyed and vulgar beyond belief.

'Show him some more of your pictures', she said.

'Shall I ?'

Though he had suffered so much from the ridicule of his friends,

Dirk Stroeve, eager for praise and naively self-satisfied, could never

resist displaying his work. He brought out a picture of two curly -

headed Italian urchins playing marbles.

'Aren't they sweet ?' said Mrs Stroeve.

And then he showed me more. I discovered that in Paris he had been

painting just the same stale, obviously picturesque things that he had

painted for years in Rome. It was all false, insincere, shoddy; and yet

no one was more honest, sincere, and frank than Dirk Stroeve.

Who could resolve the contradiction?

I do not know what put it into my head to ask:

'I say, have you by any chance run across a painter called

Charles Strickland?'

`You don't mean to say you know him ?' cried Stroeve.

'Beast', said his wife.

Stroeve laughed.

`Ma pauvre cherie.' He went over to her and kissed both her hands.

'She doesn't like him. How strange that you should know Strickland !'

'I don't like bad manners', said Mrs Stroeve.

Dirk, laughing still, turned to me to explain.

`You see, I asked him to come here one day and look at my pictures.

Well, he came, and I showed him everything I had.'

Stroeve hesitated a moment with embarrassment. I do not know

why he had begun the story against himself; he felt an awkwardness

at finishing it.

'He looked at - at my pictures, and he didn't say anything. I thought

he was reserving his judgement till the end. And at last I said:

"There, that's the lot !" He said:

"I came to ask you to lend me twenty francs."'

`And Dirk actually gave it him', said his wife indignantly.

'I was so taken aback. I didn't like to refuse. He put the money

in his pocket, just nodded, said "Thanks", and walked out.'

Dirk Stroeve, telling the story, had such a look of blank

astonishment on his round, foolish face that it was almost

impossible not to laugh.

'I shouldn't have minded if he'd said my pictures were bad,

but he said nothing - nothing.'

`And you will tell the story, Dirk', said his wife.

It was lamentable that one was more amused by the ridiculous

figure cut by the Dutchman than outraged by Strickland's

brutal treatment of him.

'I hope I shall never see him again', said Mrs Stroeve.

Stroeve smiled and shrugged his shoulders. He had already

recovered his good humour.

`The fact remains that he's a great artist, a very great artist.'

`Strickland ?' I exclaimed. 'It can't be the same man.'

'A big fellow with a red beard. Charles Strickland.

An Englishman.'

'He had no beard when I knew him, but if he has grown one

it might well be red. The man I'm thinking of only began painting

five years ago.'

'That's it. He's a great artist.'

'Impossible.'

'Have I ever been mistaken ?' Dirk asked me.

'I tell you he has genius. I'm convinced of it. In a hundred years,

if you and I are remembered at all, it will be because we knew

Charles Strickland.'

I was astonished, and at the same time I was very much

excited. I remembered suddenly my last talk with him.

'Where can one see his work ?' I asked. 'Is he having any

success ? Where is he living ?'

No; he has no success. I don't think he's ever sold a picture.

When you speak to men about him they only laugh. But I know

he's a great artist. After all, they laughed at Manet. Corot never

sold a picture. I don't know where he lives, but I can take you

to see him. He goes to a cafe in the Avenue de Clichy at seven

o'clock every evening. If you like we'll go there tomorrow.'

'I'm not sure if he'll wish to see me. I think I may remind him

of a time he prefers to forget. But I'll come all the same. Is there

any chance of seeing any of his pictures ?'

Not from him. He won't show you a thing. There's a little dealer

I know who has two or three. But you mustn't go without me;

you wouldn't understand. I must show them to you myself.'

`Dirk, you make me impatient', said Mrs Stroeve. 'How can

you talk like that about his pictures when he treated you as he

did ?' She turned to me. 'Do you know, when some Dutch people

came here to buy Dirk's pictures he tried to persuade them

to buy Strickland's. He insisted on bringing them here to show.'

'What did you think of them ?' I asked her, smiling.

`They were awful.'

`Ah, sweetheart, you don't understand.'

'Well, your Dutch people were furious with you.

They thought you were having a joke with them.'

Dirk Stroeve took off his spectacles and wiped them.

His flushed face was shining with excitement.

'Why should you think that

beauty, which is the most precious thing in the world,

lies like a stone on the beach for the careless passer-by

to pick up idly ?

Beauty is something wonderful and strange

that the artist fashions out of the chaos of the world

in the torment of his soul.

And when he has made it, it is not given to all to know it.

To recognize it you must repeat the adventure of the artist.

It is a melody that he sings to you,

and to hear it again in your own heart you want knowledge and

sensitiveness and imagination.'

`Why did I always think your pictures beautiful, Dirk ?

I admired them the very first time I saw them.'

Stroeve's lips trembled a little.

'Go to bed, my precious. I will walk a few steps with our friend,

and then I will come back.'

The End

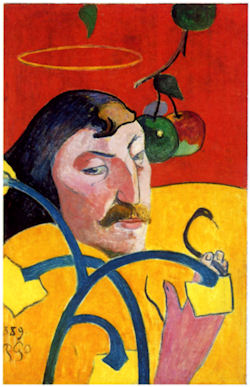

Paul Gauguin:Self-Portrait

020

Gauguin's Self-Portrait

Self-portraiture constituted a significant element of Gauguin's

production, particularly in 1888 and in 1889. Gauguin's interest

was prompted in part by Van Gogh's 1888 portrait series including

La Mousme, which he knew from Van Gogh's letters. In addition,

Van Gogh hoped to establish an artists' colony in the south that

could be analogous to Gauguin's circle in Brittany, and proposed

an exchange of self-portraits.

Gauguin's only known statements about his self-portraiture

concern one he painted in response to Van Gogh. He described

manipulating his image to accord with a predetermined symbolic

program, a program somewhat similar to the Gallery Self-Portrait

and referring to the 1888 depiction as "the face of an outlaw...

with an inner nobility and gentleness," a face that is "symbol of

the contemporary impressionist painter" and "a portrait of all

wretched victims of society."

The Gallery Self-Portrait, painted on a cupboard door in the dining

room of an inn in the Breton hamlet Le Pouldu, is one of Gauguin's

most important and radical paintings. His haloed head and disembodied

right hand, a snake inserted between the fingers, float on amorphous

zones of yellow and red. Elements of caricature add an ironic and

aggressively ambivalent inflection to this painted assertion of Gauguin's

artistic superiority and make him the sardonic hero of his new aesthetic

system.

The End

関連サイト:

予習挑戦型へ脱皮して潜在能力を開発する

Materials to Create an English Brain by the Copy-Writing Method

3.毎日コピー英作文法実践で英語脳を創る③

4.毎日コピー英作文法実践で英語脳を創る④

5.毎日コピー英作文法実践で英語脳を創る⑤

6.毎日コピー英作文法実践で英語脳を創る⑥

7.毎日コピー英作文法実践で英語脳を創る⑦